Maximilian Schell dies at 83; Oscar-winning actor

- Share via

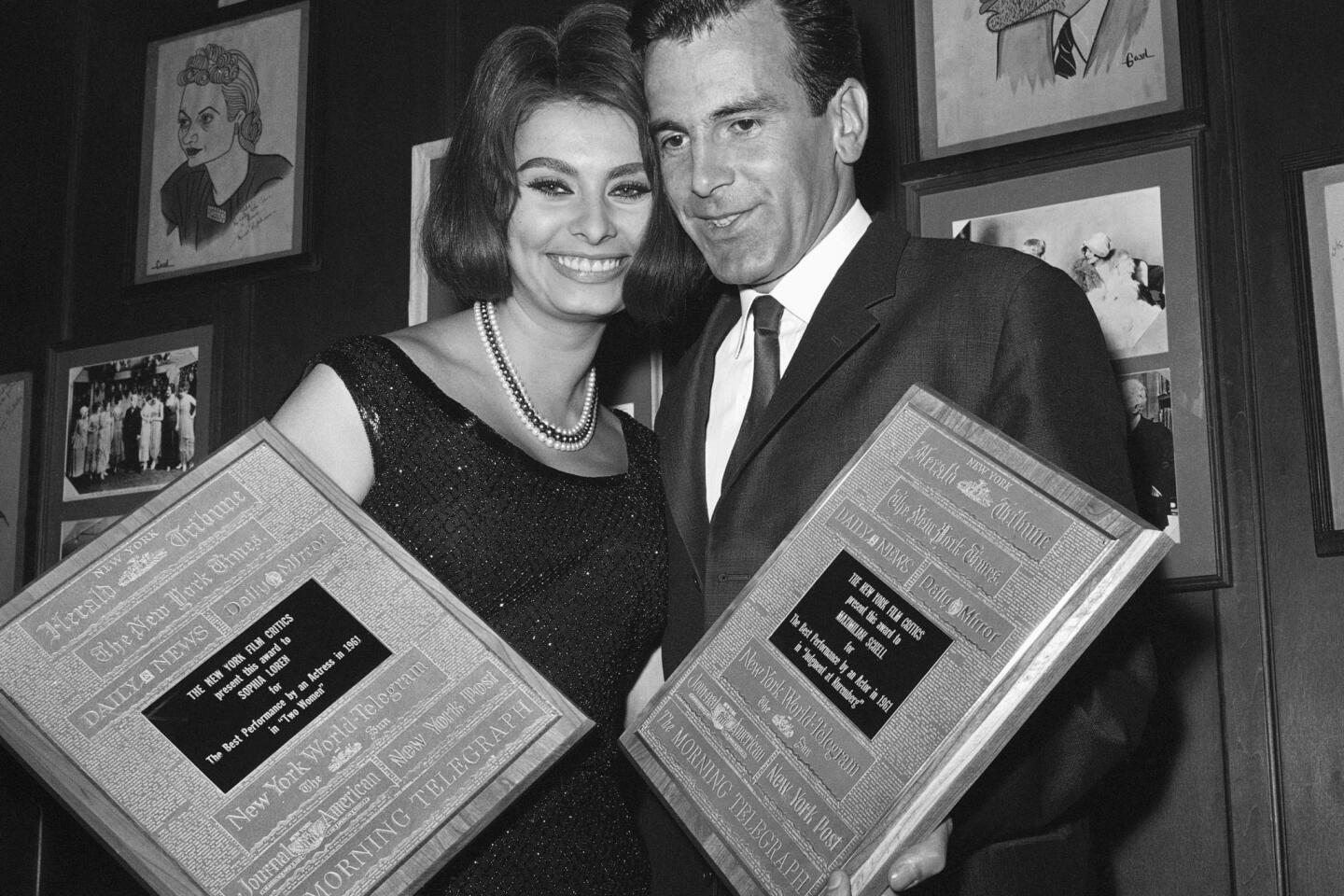

When Austrian-born actor Maximilian Schell won the best actor Academy Award in 1962 for his role in “Judgment at Nuremberg,” he gave a short thank-you speech in which he recalled being questioned by a customs official upon first arriving in the United States.

“He was asking me what I was doing here, and I said, ‘I’m going to do a film,’” Schell told the glittering crowd in his accented English. “And he said to me, ‘Good luck, boy.’ And I think that was very unusual for a customs man. And I can tell him now that I had it.”

Undoubtedly, Schell, whose family fled the Nazis when he was a boy, made his own luck — not only as a celebrated actor who amassed more than 100 film and TV credits, but also as a director of films, documentaries, plays and opera.

Schell, 83, died early Saturday in a hospital in Innsbruck, Austria, of natural causes, according to his European agent, Patricia Baumbauer. Schell’s wife, Iva, was with him when he died. They were married in August.

Schell’s career in the U.S. began with a role as a Nazi officer in the film “The Young Lions” (1958). He said his English was limited at the time and that he had an unlikely tutor — Marlon Brando, one of the stars of the film, famous for his mumbling. “Marlon was extremely kind to help me with the part,” Schell told the Associated Press in a 1990 interview.

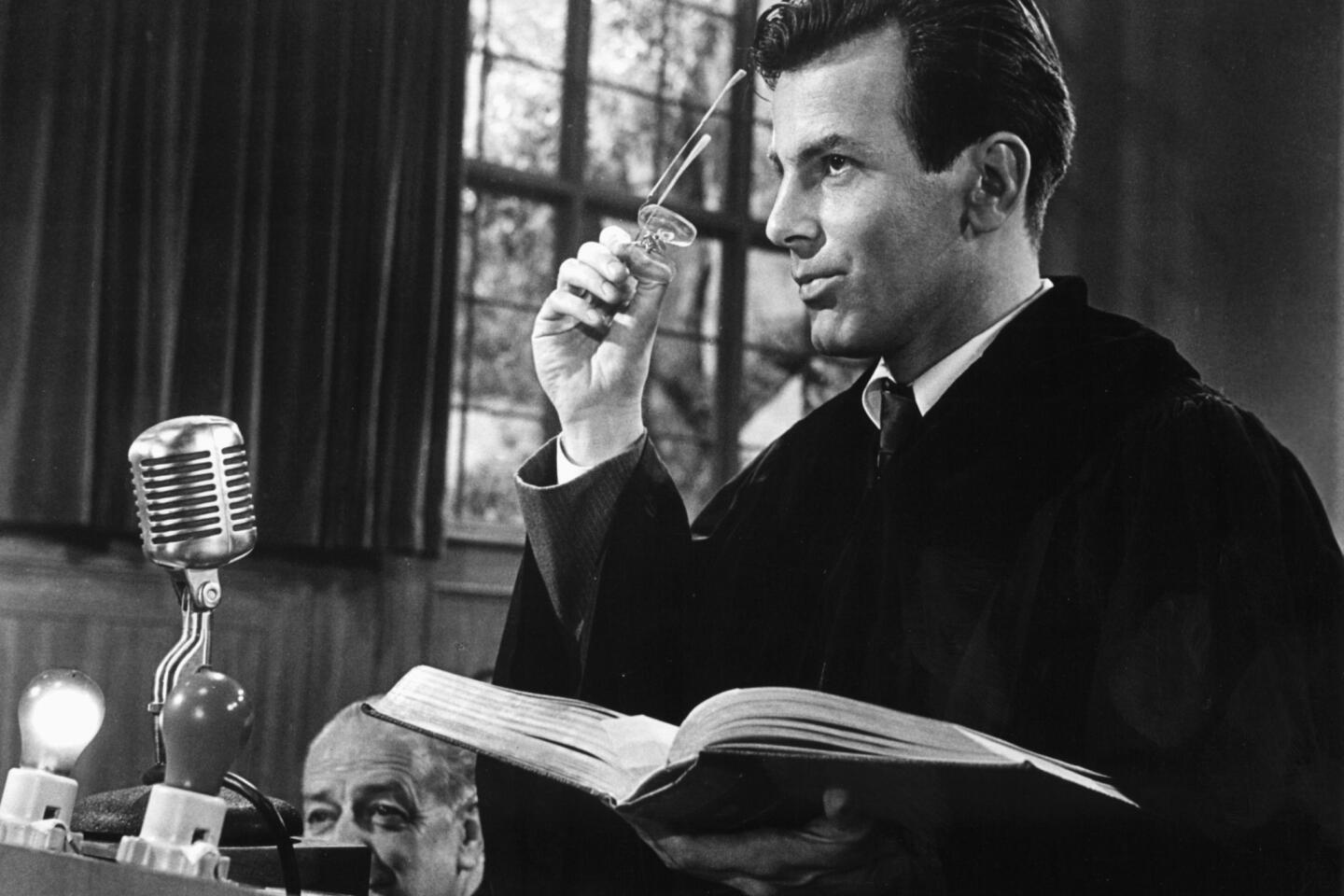

A year after “Young Lions” came out, Schell played, for the first time, the most famous role of his career, attorney Hans Rolfe in “Judgment at Nuremberg.”

That was in a televised “Playhouse 90” version of the Abby Mann-penned script. When it came time for the star-studded film version, Schell didn’t seek to again play Rolfe, the fictionalized lawyer who vehemently defends Nazi judges.

“I wanted to do Burt Lancaster’s role as the Nazi judge who doesn’t say much,” Schell told the Hollywood Reporter in 2011. But director Stanley Kramer insisted he reprise his role as the attorney, and Schell, in the view of some critics, walked away with the film. One of the actors he beat for the Oscar was Spencer Tracy, who also appeared in the movie.

Schell played numerous high-profile screen and stage roles, including a celebrated “Hamlet,” in his career. But “Judgment at Nuremberg” always remained a highlight. “Some of your work you forget,” he told the New York Daily News in 2001. “This one, I didn’t forget.”

Schell was born in Vienna on Dec. 8, 1930, to a poet father and actress mother. In 1938, when the Nazis annexed Austria, the family fled to Switzerland. Schell studied at the University of Basel and had several stage roles before getting his first film parts in the mid-1950s. In the U.S., starting with “The Young Lions,” he was cast in several films about the war, often as a Nazi soldier, sympathizer or resister.

He was nominated for an Oscar for his starring role in “The Man in the Glass Booth” (1975) about a wealthy industrialist who is kidnapped and put on trial in Israel for war crimes. Another nomination came for his relatively small part in “Julia” (1977), in which he plays a man trying to arrange the smuggling of funds into Germany to help support the anti-Nazi underground.

But there were other types of roles. In the comic heist film “Topkapi” (1964) he plays a master criminal, and he reunited with his friend Brando for the comedy “The Freshman” (1990). He also played historic characters, such as Lenin in the HBO film “Stalin” (1992).

And there were roles in big-budget sci-fi films, such as “The Black Hole” (1979) and “Deep Impact” (1998).

The handful of films he directed were in some cases highly personal. The documentary “Marlene” (1984) is largely about him trying to get an aging Marlene Dietrich — who was also in “Judgment at Nuremberg” — to appear on camera. She refuses, but Schell’s mixture of their recorded conversations and archival footage resulted in a highly praised film.

In an interview with British documentary filmmaker John Henderson, Schell said he felt at the outset that it would be “interesting to make a film of denial. Somebody doesn’t want to be filmed, which has a whole lot of reasons: beauty or lost beauty or not to be reminded of better times, age, those sort of things. So, that was in a way the key.”

Critics were less praising of his film about the declining years of his sister, actress Maria Schell. Reviewer Roger Ebert called “My Sister Maria” (2002), which was a mixture of documentary and staged footage, “brave, heartless, and exceedingly strange.”

Two of Schell’s large-scale opera productions were done by Los Angeles Opera. Mark Swed, music critic for the Los Angeles Times, said Schell’s 2001 version of Richard Wagner’s “Lohengrin” was invigorated by Schell’s “unusually realistic and compelling direction,” and Swed called the production “a watershed for the company.”

There were also critical raves for the new production of Richard Strauss’ “Der Rosenkavalier” that Schell directed for L.A. Opera in 2005. In an interview in The Times before that opera opened, Schell talked about the challenges and joys he finds in the work.

“Directing is like meeting a woman,” he said. “You don’t know her, but something strikes you and then you just have to go into it. Michelangelo said that in every rock there’s a figure hidden. All you have to do is carve it out. With care, not haste.”

In addition to his wife, Schell’s survivors include his daughter, Nastassja, from a previous marriage to actress Natalia Andreichenko that ended in divorce, and a grandchild.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.