As Denver enjoys boom times, the homeless go into hiding

- Share via

Reporting from Denver — Jerry Burton stands beneath a tall tree, a lonesome sentinel on a forlorn stretch of grass and dirt the homeless call “Resurrection Village.”

“I love this spot,” he says with a broad smile. “That’s the tree of life there, the magic tree, and if it could talk, it could tell a lot of stories.”

One of those stories might be how the impeccably polite former Marine cares for this little patch of earth. How he sweeps and rakes his “yard” while adorning the chain-link fence behind with faded plastic flowers.

Part of this is pride, the other part self-preservation. A tidy space without tents or evidence of camping is less likely to provoke the authorities.

And like so many homeless here, Burton, 54, is on high alert these days.

Salvatore Garofalo sits in a lawn chair in a makeshift homeless camp across from the Denver Rescue Mission in downtown Denver.

In March, public works employees backed by police dismantled homeless encampments near Coors Field, home of Major League Baseball’s Colorado Rockies, saying they had become health and safety hazards. Many fled to Resurrection Village, an empty lot named after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 tent city in Washington, D.C. But the city swept in the next day.

Images of workers carting off the meager possessions of the homeless and putting them into storage made national news. Yet it was just the latest effort aimed at a growing indigent population that has defied attempts to rein it in. There have been laws targeting panhandling and bans on “camping” or sleeping on sidewalks designed to get people into shelters.

“The cops used to come by a few times a year; now it’s twice a night,” said Ray Lyall, 58. “They shine a light in our eyes and tell us if we stay they’ll take our stuff. Then they say they’ll take us to a shelter. The shelters are disgusting. Shelters are for dogs.”

While cities across the nation are wrestling with homelessness, the problem is especially acute in Denver, where skyrocketing home prices, an influx of newcomers and a booming marijuana trade have helped swell the ranks of those living on the streets.

“A lot of people are coming to Denver, and a percentage of them are going to be homeless,” said Tom Luehrs, executive director of the St. Francis Center, a local day shelter. “The economy is good, Colorado is a Medicaid-eligible state, and legalized marijuana is a big draw. In many ways, it’s the perfect storm.”

Back in 2005, then-Mayor John Hickenlooper announced plans to end homelessness in 10 years. When that didn’t work, a city auditor’s report criticized the effort, saying it needed to update its mission, focus and data collection.

As Denver police look on, homeless people gather their belongings and leave a camp around a small park near the Denver Rescue Mission.

“Who could have foreseen the Great Recession?” said Bennie Milliner, executive director of Denver’s Road Home, the city agency leading anti-homeless efforts. “The homeless problem was greatly exacerbated by the housing downturn and the bursting of the housing bubble.”

Now the opposite is true. The Denver-Aurora metro area has seen a 26% increase in home prices over the last two years, one of the highest in the country. Investors are buying up properties and selling them for top dollar. Condos are going for $500,000 a few feet from people sleeping on the street. And warehouses that might have been used for shelters are snapped up to grow marijuana.

An estimated 3,737 homeless now live in Denver. Activists say that’s a 10% increase over the last two years, and those numbers are considered low.

Mayor Michael Hancock wants 3,000 affordable housing units available in the next five years, and $47 million has been allocated for homeless outreach this year.

Yet critics believe the city is applying bandages when major surgery is needed.

The American Civil Liberties Union says Denver and other Colorado cities are criminalizing homelessness. Last October, they successfully sued Grand Junction over a panhandling ordinance that was deemed a violation of the 1st Amendment. As a result, many communities are now reluctant to enforce their own panhandling laws.

Meanwhile, the Denver Rescue Mission, the city’s largest and oldest, is serving 900 people a day.

“When marijuana was legalized we saw a substantial increase in numbers of homeless,” said Steve Walkup, who has run programs at the mission for 20 years. “People come out here because they hear great things about Denver, then realize costs are three times higher than back home. They can’t rent a place or buy a place and end up on the streets.”

The 120-year-old mission, which housed prostitutes during the Gold Rush, is illuminated by a large white cross with “Jesus Saves” inscribed on it.

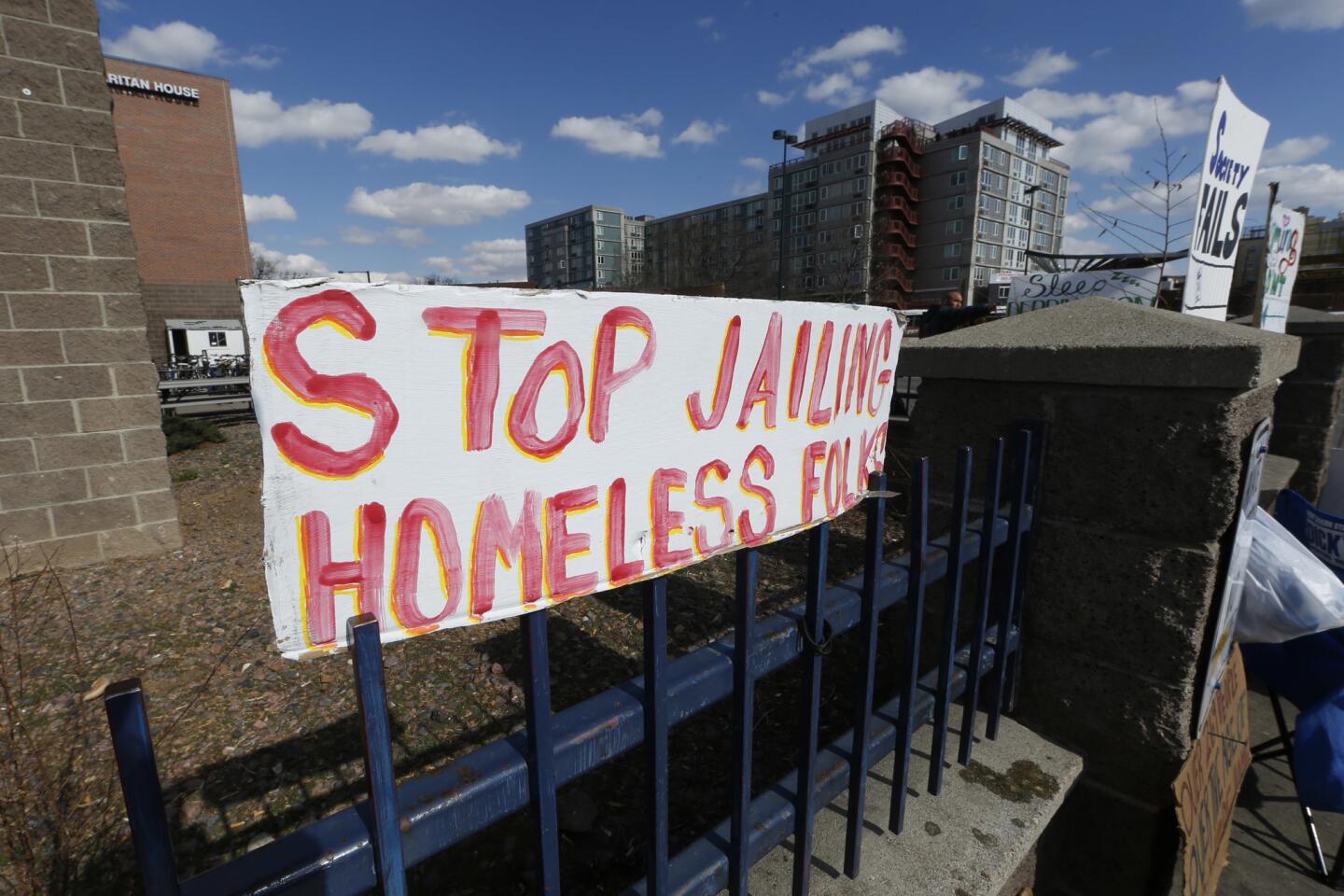

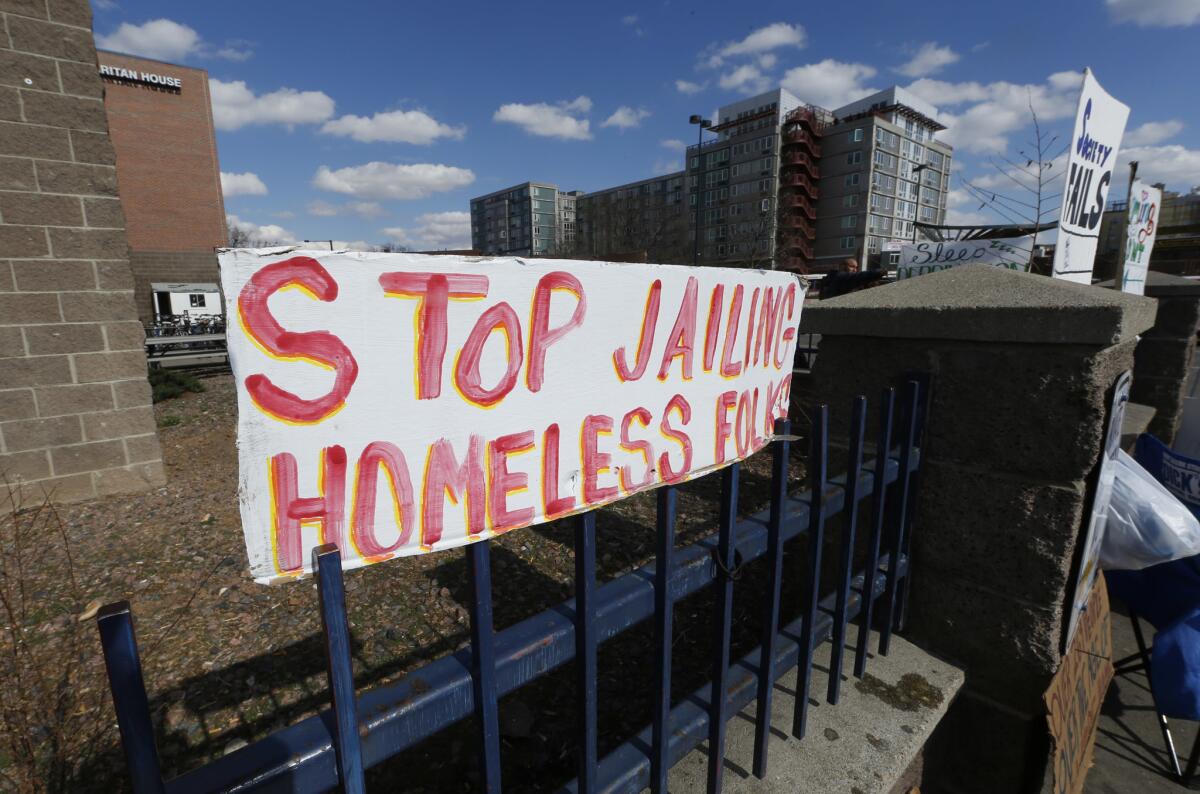

A sign hangs on a fence around the Samaritan House in Denver as homeless people from a camp are moved by the city. A new high-rise apartment building can be seen in the background.

Most nights, the homeless sleep in row upon row of bunk beds on the second floor.

Walkup said the encampments taken down by the city were rife with gambling, drug dealing and prostitution.

“But they’ll probably rebuild their shantytowns,” he said. “One will go up and another and another.”

On a recent afternoon the mission’s courtyard was crowded, the mood edgy. A belligerent man ranted about having to wait for a bathroom. Police were summoned when one resident accused another of stealing his money.

A knot of people sat around a metal table looking tired.

Ashley Grant, 23, said she lost her home after the landlord raised the rent from $750 to $1,000 for a two-bedroom apartment. Her mother is also homeless.

“I work at a call center right now, and I’m going to do day labor so I can get enough money to get my mom into a hotel room,” she said. “It will be a cold day in hell when I let my mother sleep outside.”

Many homeless shun shelters, saying they are overcrowded and infested with bedbugs and sick people. But with stepped-up police patrols, they are receding further into Denver’s nooks and crannies.

“Being hidden is preferable, but it also means being less safe, especially for women,” said Terese Howard, an activist with Denver Homeless Out Loud, which is working to overturn the camping ban.

They are also trying to win approval for a “tiny home” community in Denver for the homeless. The houses measure 8-by-12 feet each. Howard said there are 17 such villages across the country.

Traffic passes by the belongings of a homeless person evicted from a camp near the Samaritan House in Denver.

A prototype is attached to a pickup owned by the organization. Jerry Burton sometimes sleeps in the truck when it’s parked near Resurrection Village.

Burton has an easy smile and thoughtful demeanor.

“I became homeless because of some bad decisions on my part,” he said. “I used to work as a cook and would come back here and lay out my stuff. I made a point of keeping it clean. The more I kept it clean the more people would come and stay.”

A homeless woman wandered by, and then a man with a bruised face staggered up.

“The people in this neighborhood treat us like human beings,” he said, his voice breaking. “I wish the city would.”

Burton looked stricken.

“No man can tell me I can’t sit here and rest, not the mayor, not even President Obama,” he said.

The nightly visits by the police have made him more defiant.

“They say, Get up and move, you can’t sleep here,’ and I won’t get up,” he said. “They don’t want to arrest me because it looks like they’re criminalizing homelessness. To be honest, I don’t think their heart is in it.”

For now, Burton is keeping his tent and few belongings in the truck.

“I have a God-given right to survive,” he said. “And that’s what I’m going to do.”

Kelly is a special correspondent based in Denver.

ALSO

Voting has gotten tougher in 17 states, and it could alter elections

Seattle councilwomen’s vote against NBA plan inspires sexist rage

North Carolina says it will defy Justice Department over LGBT law: ‘We’re not going to get bullied’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.