Activists kick off new Poor People’s Campaign, echoing MLK in 1968

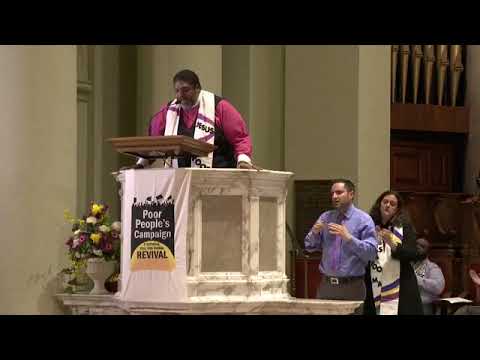

The Rev. William Barber, co-founder of the revived Poor People’s Campaign, speaks during the launch of the campaign Sunday in Washington.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Callie Greer, a community organizer from Selma, Ala., on Monday stepped on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol, a strip of sackcloth fastened around her upper left arm to signal she was willing to go to jail.

Greer lost her daughter Venus, who could not afford health insurance, to breast cancer in 2013. For that reason, she was one of hundreds of protesters who had traveled to Washington to focus attention on the plight of poor people in America.

“My baby didn’t have to die,” said Greer, 58, whose state legislators refused to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. “I’m going to jail today for a good reason.”

Hundreds of poor and low-wage workers, clergy and activists were arrested Monday outside the U.S. Capitol and at statehouses across the country as they kick-started a revival of the Poor People’s Campaign — the civil disobedience movement founded 50 years ago by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The 40 days of planned protests and other activities, organizers said, are intended to highlight the issues of systemic racism, poverty, ecological devastation and the societal cost of America’s military buildup.

The idea is to lift poor people to the top of the nation’s agenda, disrupting the mainstream political conversation and jolting lawmakers, pundits and the 24-hour news cycle dominated by the Trump administration.

A looming question, as organizers pledge to usher in one of the largest waves of nonviolent direct action in U.S. history, is whether the campaign’s message will gain traction.

A movement to fight poverty across racial lines could be a tough sell at a time when many poor whites voted for politicians who oppose minimum or living wage laws. At the same time, not all poor African Americans consider their struggle to be the same as that of poor whites.

In Washington, a crowd of several hundred protesters from states as far afield as Alaska and Florida, California and Maryland, held up signs declaring “The War on Poverty Is Immoral” and “We Are a New Unsettling Force.”

Many fastened yellow pieces of paper to their bodies, detailing poverty statistics such as “62 million people work for less than a living wage” and “There are 38 million poor children in the U.S.”

“We are here to make our voices heard,” the Rev. Liz Theoharis, a Presbyterian minister from New York and co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, told the crowd gathered in front of the Capitol. “To tell this nation that there are 140 million poor people living in it…. There comes a time when silence is betrayal. There comes a time when we cannot take it anymore.”

The Rev. William J. Barber II, a pastor from North Carolina and the campaign’s other co-chair, called for a “revolution of values.”

“We have come to put our mouths and our bodies on the line,” he said. “We’ve come to put forward the people who are hurt by the policy violence, because you can’t change the narrative until you change the narrator.”

When Greer stepped up to the stage, she abandoned the speech she had written.

“I’m wailing,” she screamed into the microphone. “How many more babies? How many more children?” As she collapsed in sobs, Barber took over.

“That’s what the nation ought to hear,” he said as she cried. “Her daughter died because Alabama refused to expand Medicaid…. We need to make this nation cry.”

Carolina Alas, a fast-food worker from Richmond, Calif., told the crowd that she did not earn enough to support her family.

The 48-year-old — a U.S. citizen from El Salvador — said she worked 40 hours a week cooking hamburgers at a Jack in the Box. But she still struggles to pay her $700 rent and phone and medical bills on an $11-an-hour salary. She said she could not afford a car, dinner out or even a pain reliever if she had a headache.

Fifty years after King was assassinated, about 41 million Americans live below the official poverty line. Many more barely scrape by. In 2016, 1% of Americans held 20% of the nation’s wealth, up from 12% in 1968; the percentage of U.S. families subsisting below the official poverty rate is stuck at about 10%, according to the Institute for Policy Studies.

Organizers with the Poor People’s Campaign say official measures of poverty are too narrow and do not take into account the number of people struggling in an era of stagnant low wages and steep rises in rents and living expenses. If food, clothing, housing and utility costs, as well as government assistance programs, are factored in, they say, the number of poor and low-income Americans swells to 140 million, about 43% of the population.

At the end of the rally in Washington, Barber and Theoharis — both wearing white clerical stoles that said “Jesus was a poor man” — slowly marched onto 1st Street, behind a large banner proclaiming: “We can’t go down this road any longer.”

Carrying bullhorns, they led the crowd in a civil rights anthem:

Turn me ’round

Turn me ’round

I’m gonna keep on walkin’

Keep on talkin’

Marchin’ into freedom land.

A protester near the front held a large placard listing some of the campaign’s policy demands: ending child poverty; equal pay for equal work; a guaranteed annual income; fully-funded welfare programs; safe public housing for the poor; a repeal of the 2017 federal tax law.

As the marchers neared the Library of Congress, a police line blocked their path.

“If you don’t leave the roadway, you will be placed under arrest,” an officer announced as more than 100 protesters remained on the road.

The crowd refused to move, singing, “We won’t be silent anymore.”

In the late 1960s, King outlined his plan to build a Poor People’s Campaign as he began to worry that the passing of landmark laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had not fundamentally shaken up inequality in America.

In May 1968, a month after King was assassinated, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference forged ahead with his plan, and thousands of poor people traveled to Washington to set up a shantytown known as “Resurrection City” on the National Mall. Calling for a $30-billion annual appropriation for a comprehensive anti-poverty effort, they demanded full employment, a guaranteed annual basic income and construction funds for at least 500,000 units of low-cost housing a year.

The campaign, however, was beset with organizational problems as it struggled to provide food, shelter, clothing and basic services. Before long, rain turned the National Mall into a field of mud, drenching the wooden shacks and canvas tents. Eventually, thousands of police officers helped evacuate the shantytown residents.

Unlike that campaign, the current effort is not calling for poor people to camp in the nation’s capital until its demands are met. After six weeks of protests and teach-ins, organizers said, poor people will join together on June 23 for a mass mobilization outside the Capitol and then return to their states to continue building a multi-year campaign.

On Monday, after a half-hour standoff in the middle of the street, officers fastened red wrist bands around more than 200 protesters who had refused to move — including Barber and Theoharis. They were detained in metal pens on the lawn of the Capitol before being processed by law enforcement and released.

As a crowd gathered on the other side of the yellow police tape, protesters waved Poor People’s Campaign banners and sang, “One jail is not enough for all of us.”

Many protesters said they planned to continue next week with more activities across the country.

“Once you ring a bell, you can’t unring it,” Greer said. “We’re ringing a bell, and people will hear it.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent.

UPDATES:

8:10 p.m.: The article was updated with comments and descriptions related to the revival of the Poor People’s Campaign.

The article was originally published at 9:20 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.