St. Louis-area protesters win restraining order limiting police use of tear gas

- Share via

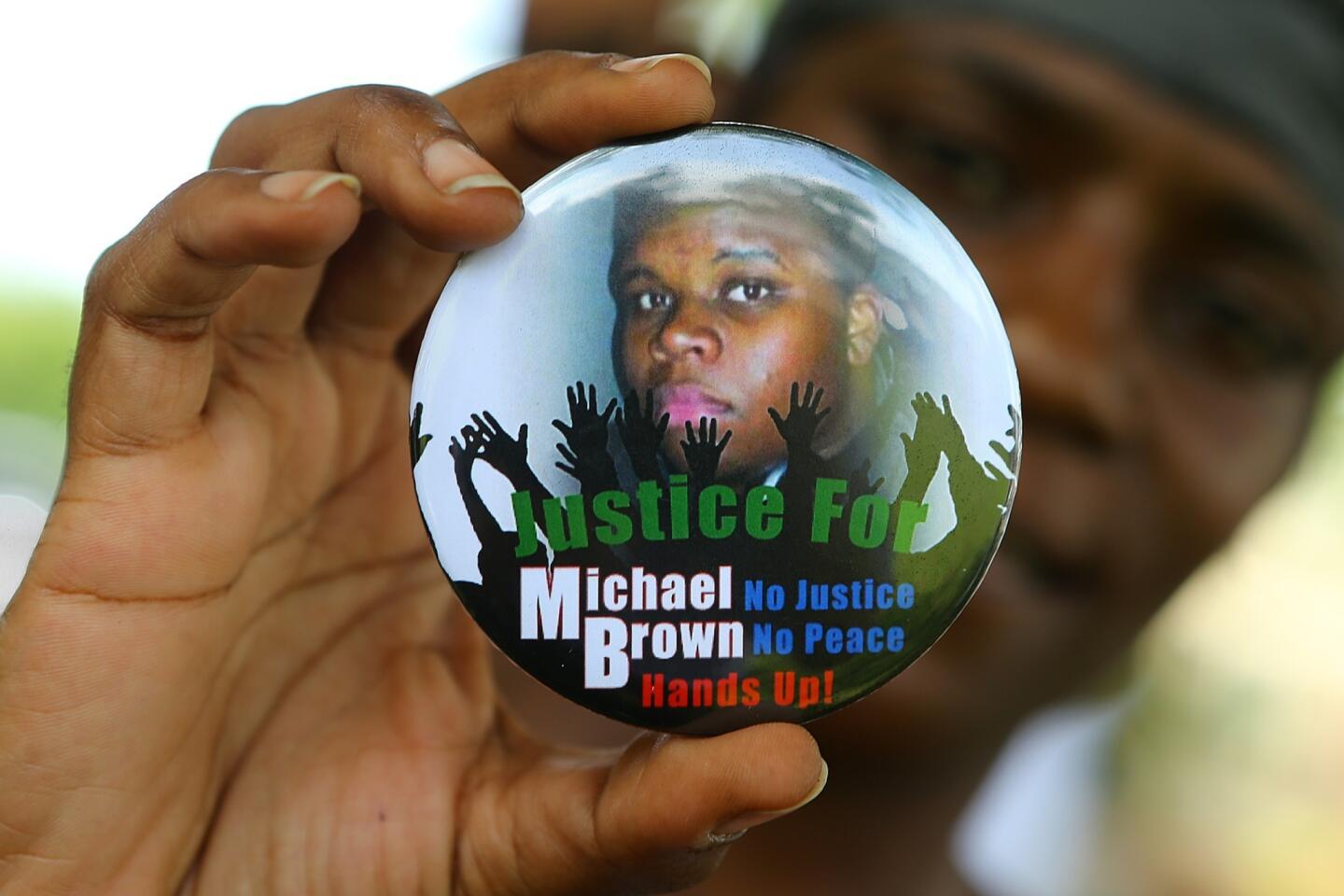

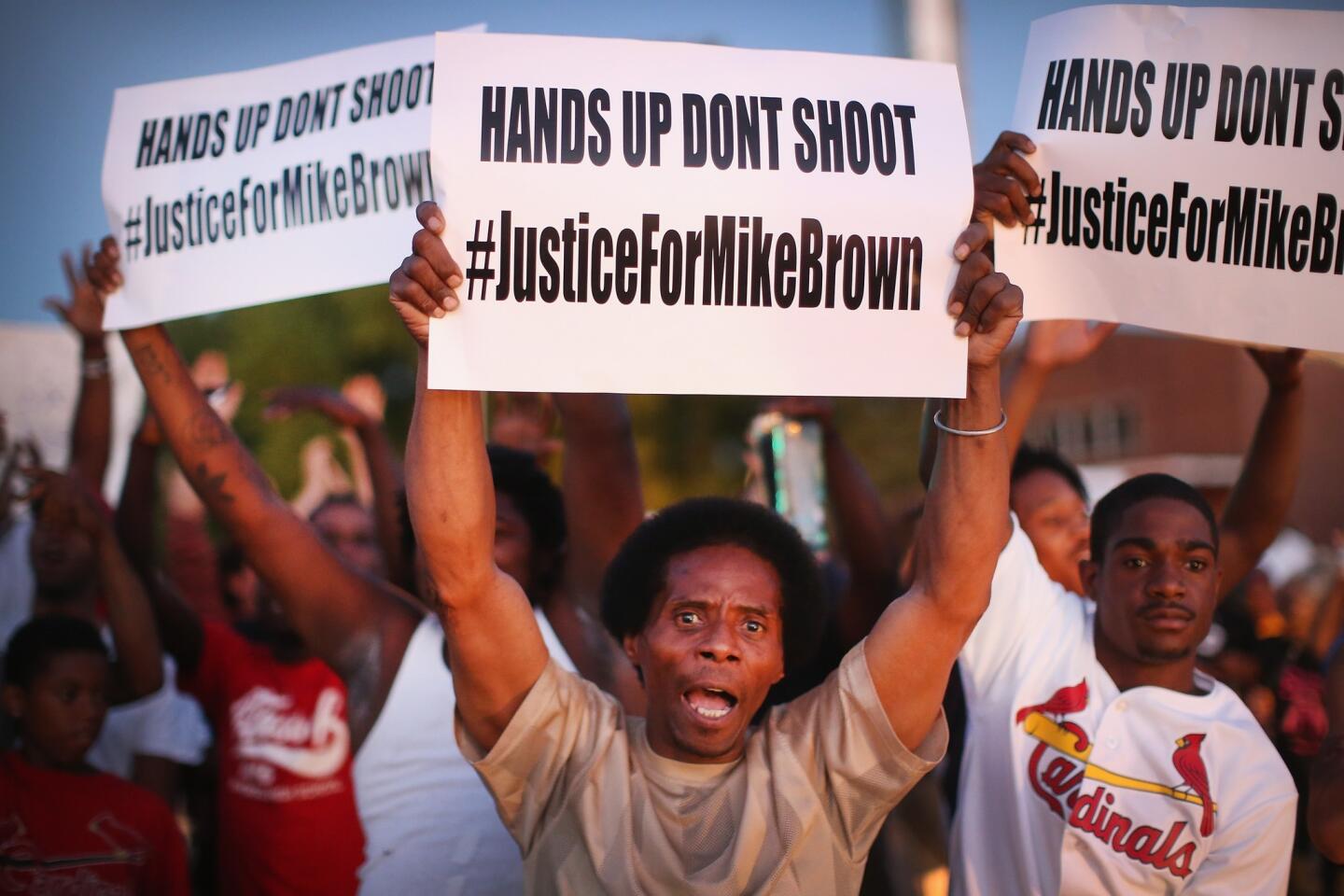

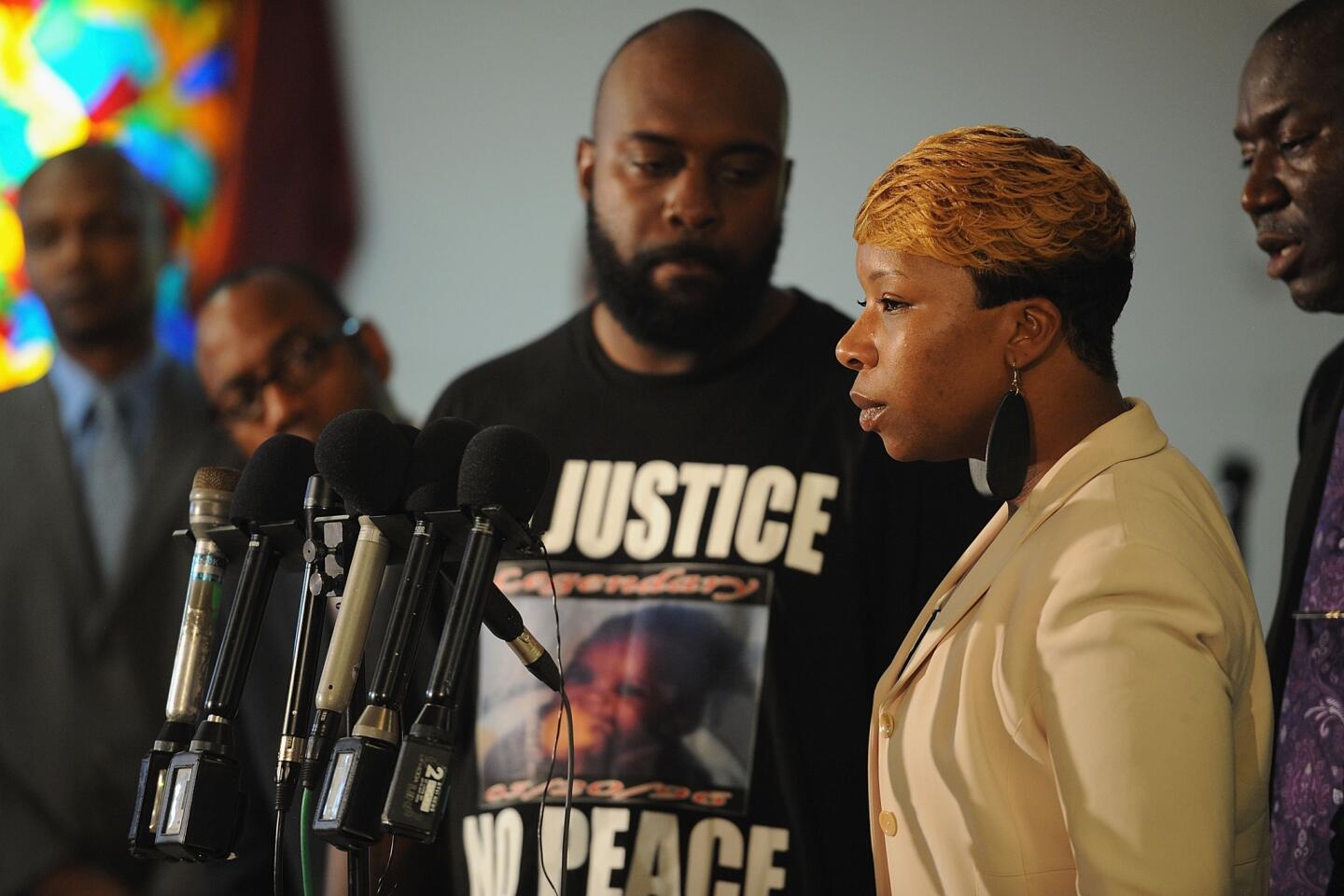

A federal court has issued a restraining order to curb St. Louis-area law enforcement agencies’ use of tear gas and chemical sprays, a decision prompted by police actions during days of protests following a grand jury’s decision not to indict a Ferguson, Mo., police officer who fatally shot Michael Brown, court filings show.

Police must give “clear and unambiguous warnings” and provide demonstrators ample time to flee an area before they deploy chemicals deterrents against protesters, U.S. District Judge Carol Jackson in St. Louis said.

“The evidence also establishes that the law enforcement officials failed to give the plaintiffs and other protesters any warning that chemical agents would be deployed and, hence, no opportunity to avoid injury,” the ruling reads. “As a result, the plaintiffs’ ability to engage in lawful speech and assembly is encumbered by a law enforcement response that would be used if a crime were being committed.”

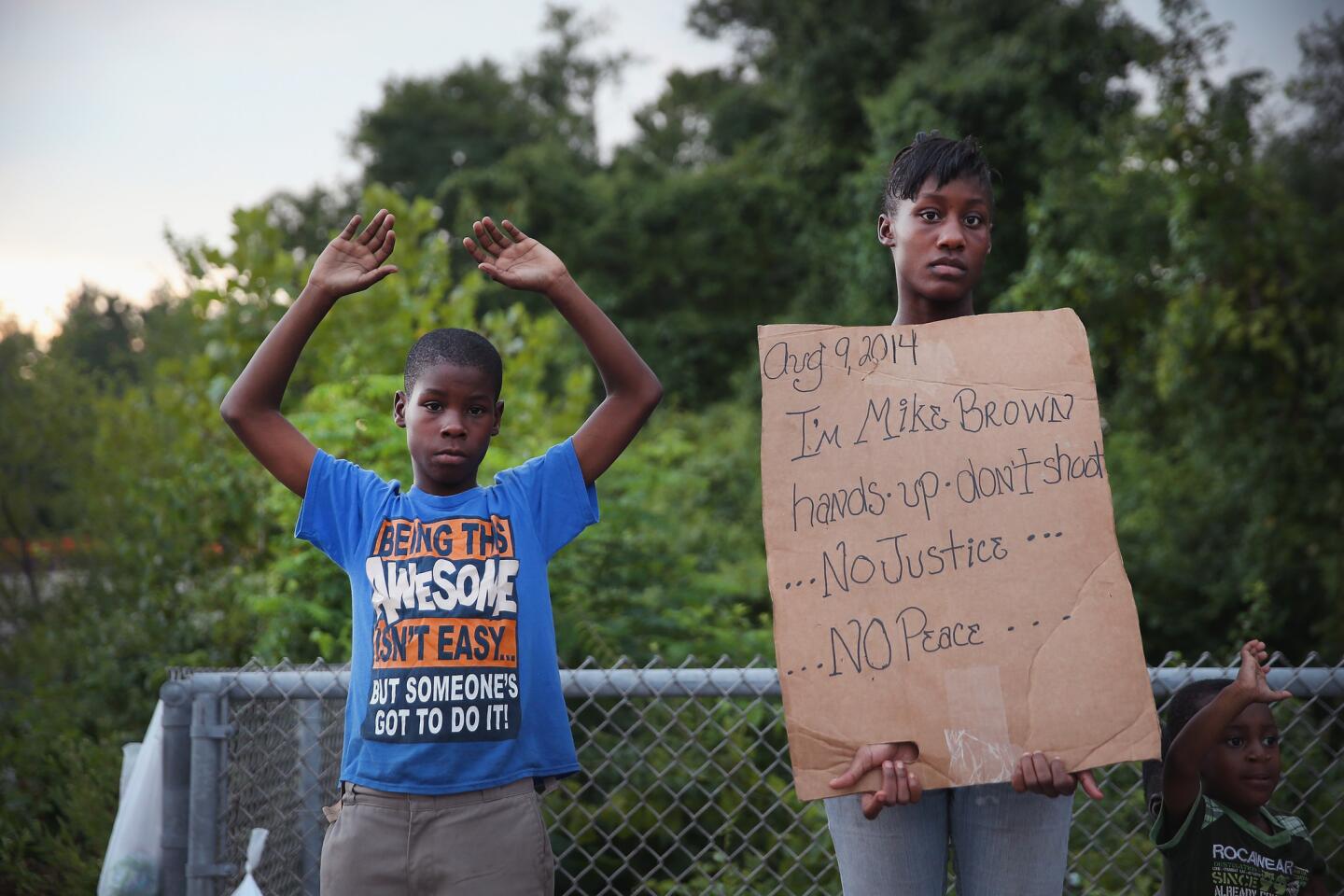

The plaintiffs, seven demonstrators who contend they had been hit with various chemical agents while peacefully demonstrating in Ferguson and St. Louis, called for the restraining order against the St. Louis County Police, St. Louis Metropolitan Police and the Missouri Highway Patrol.

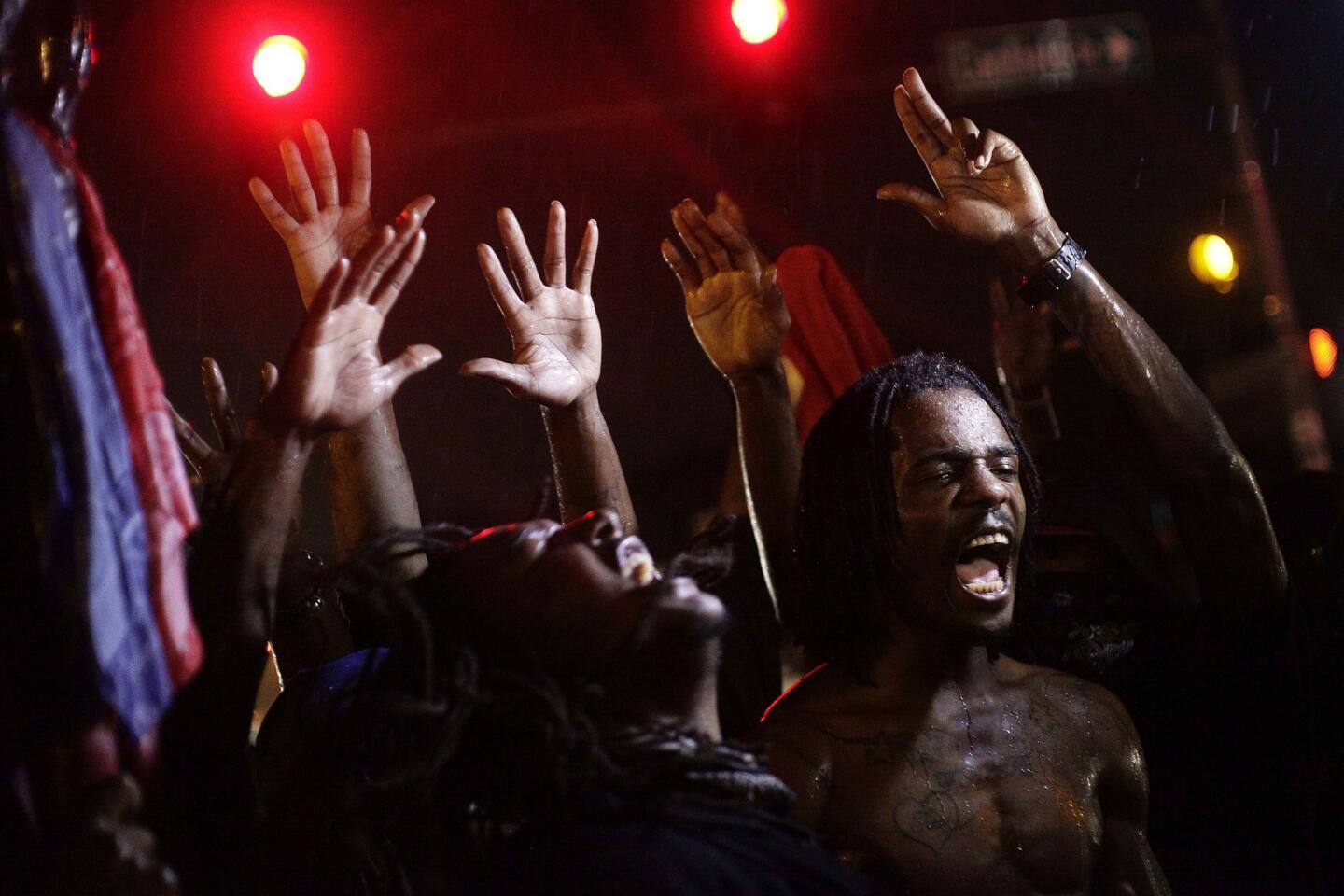

During the at-times violent protests that followed the grand jury’s decision not to indict Officer Darren Wilson in November, police would often use a loudspeaker to warn unruly protesters that they were part of an “unlawful assembly.” They would then wait several moments before deploying tear gas or smoke canisters.

Pepper spray seemed to be used more freely. Officers were spotted using the spray outside the Ferguson Police Department’s headquarters on several occasions, sometimes striking members of the media and legal aid observers not involved in the demonstrations.

“The ruling sends a strong message that police acting under the Unified Command must respect the rights of protesters to demonstrate, and cannot use excessive tactics to curtail their message,” Denise Lieberman, a senior attorney with the Advancement Project who presented testimony during the hearing, said in a statement. “Police overreach was exactly what people were protesting in the first place.”

A spokesman for the Highway Patrol referred questions to the Missouri Attorney General’s Office, which did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Jeff Rainford, chief of staff for the city of St. Louis, said the restraining order is consistent with the city police department’s existing policy; he called the protester’s initial requests to limit police use of force overly broad.

“The court gave the plaintiffs very little of what they demanded, and instead issued a common sense order that will allow St. Louis Metropolitan Police to continue to protect protesters’ constitutional rights, keep people safe and protect people’s homes and businesses,” he said in a statement.

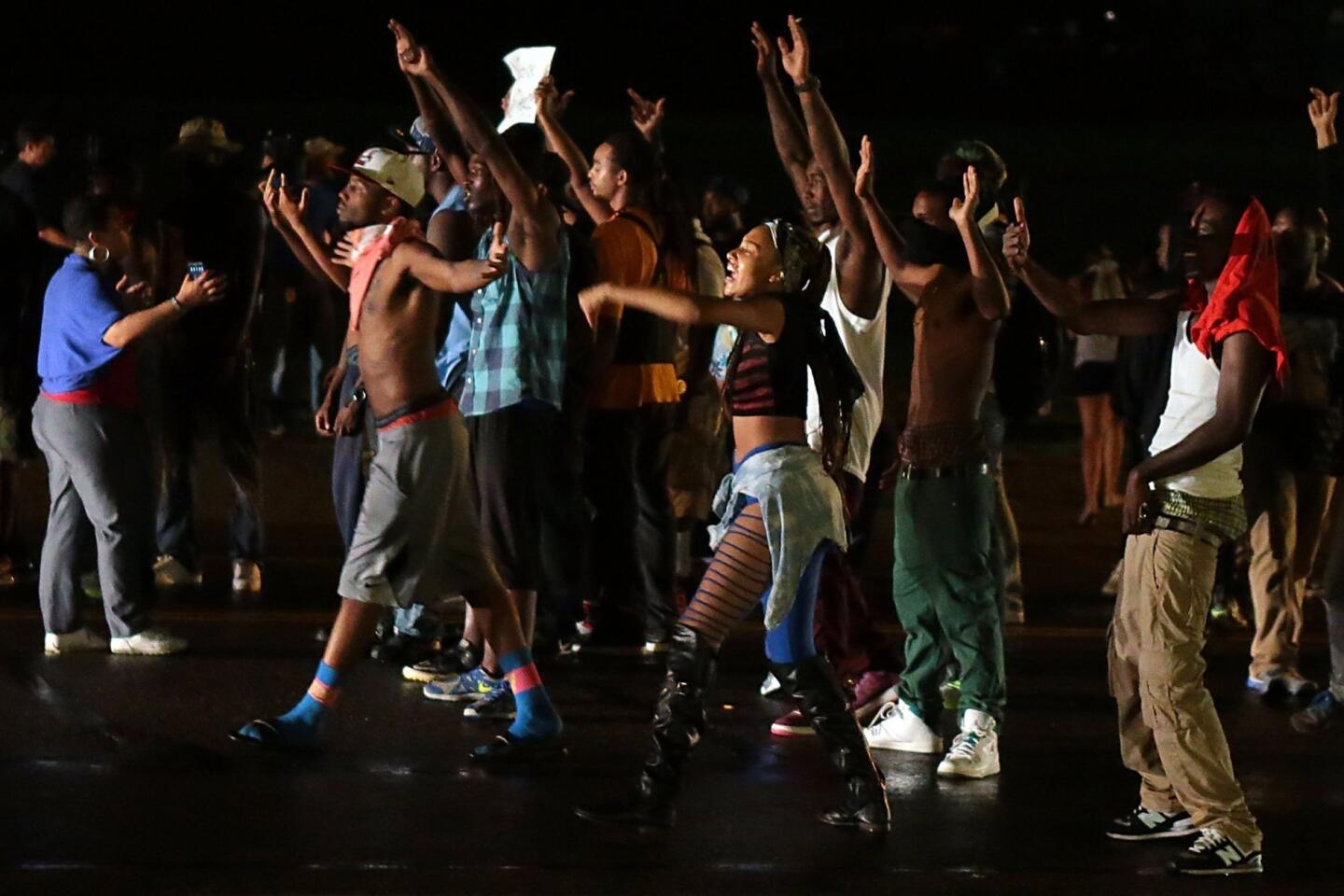

Recent grand jury decisions involving Brown and New York City resident Eric Garner, who died after a city police officer placed him in what many have described as a choke hold, have set off nationwide protests, but none have been as violent or chaotic as those near Ferguson.

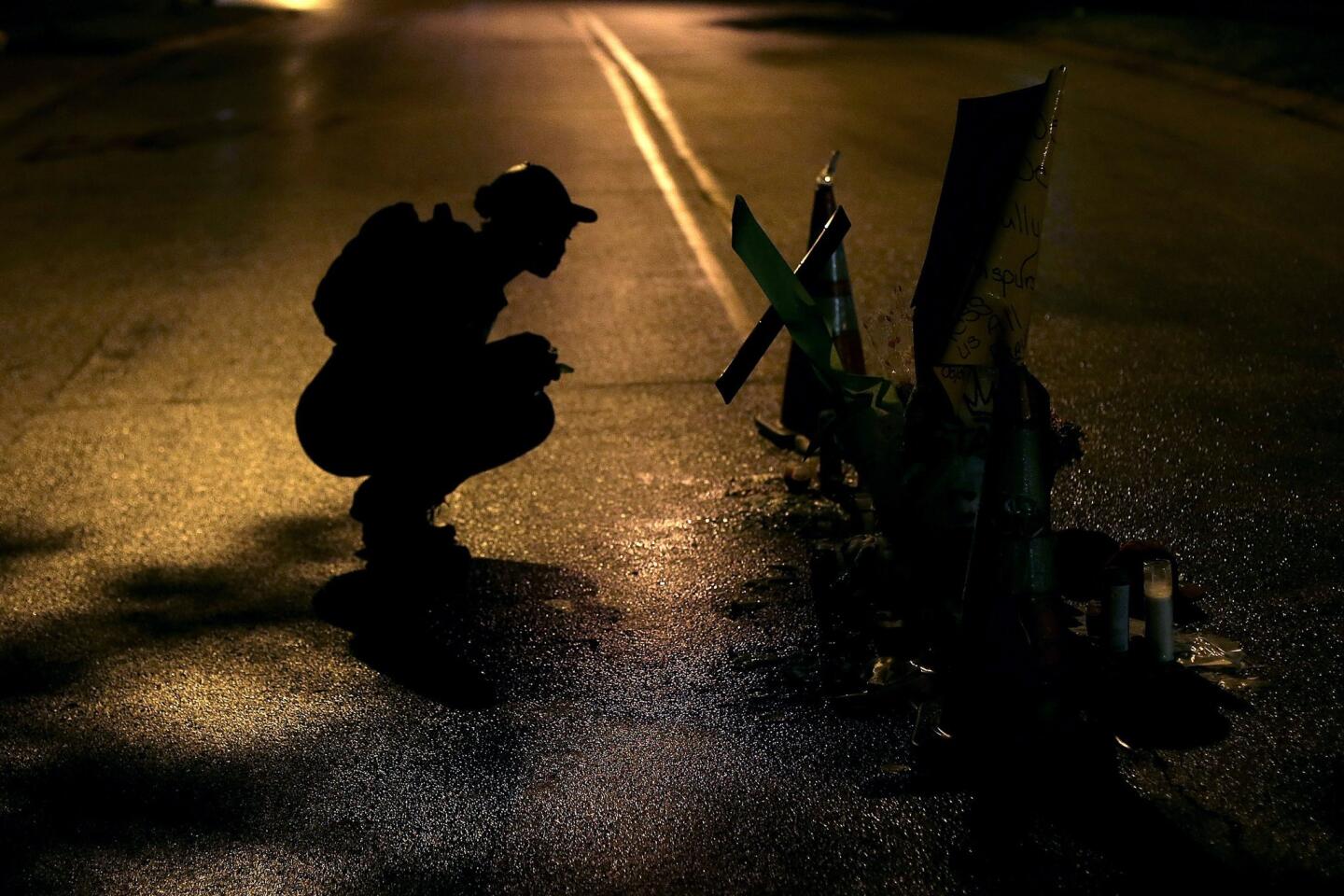

West Florissant Avenue, one of Ferguson’s main thoroughfares, was the site of several fires and lootings after the decision was announced on Nov. 24. Hundreds have been arrested during protests in the area.

Protests in Oakland, Berkeley and San Francisco have also grown unruly in recent weeks, and a series of anti-police demonstrations in Oakland this week resulted in looting, vandalism and clashes between police and civilians. A photo of an undercover California Highway Patrol officer aiming a gun at demonstrators in Oakland roiled protesters this week, but police contend the officer was protecting his partner from an assault.

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT for breaking news

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.