Holocaust suspect dies in Michigan after avoiding deportation

- Share via

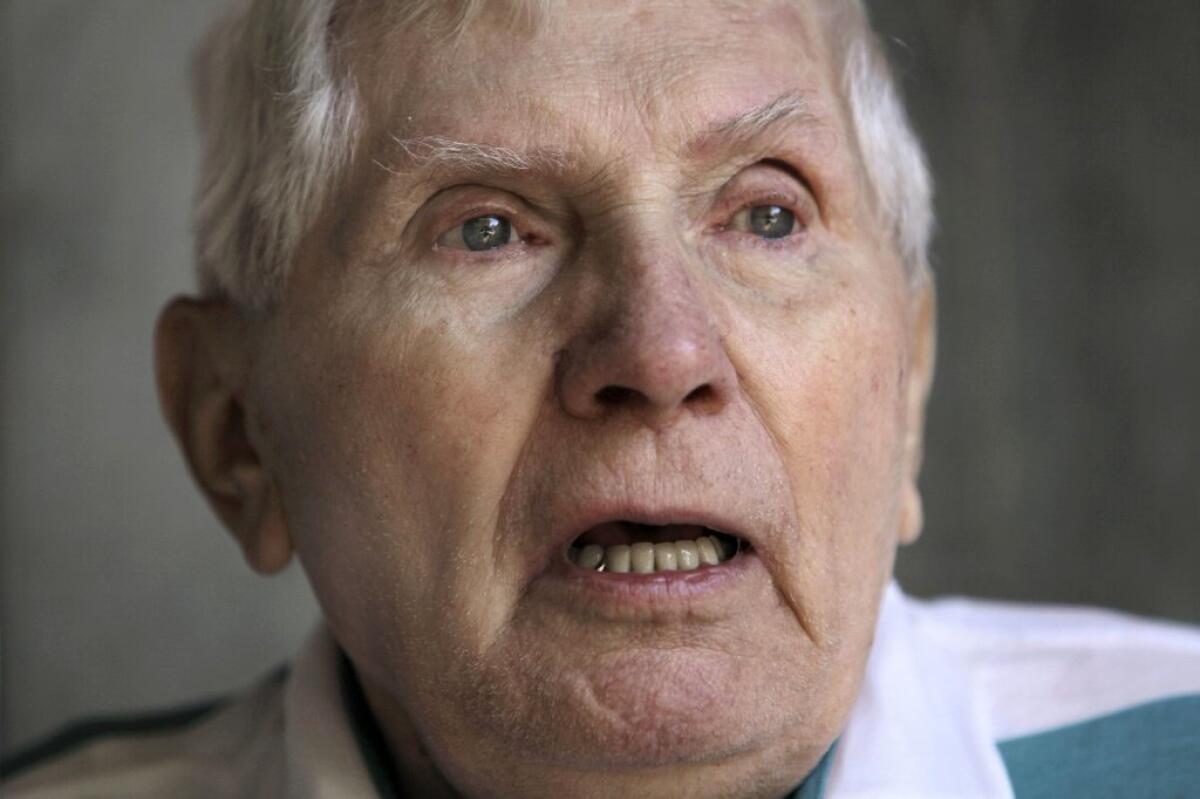

John Kalymon had long insisted that he was not a war criminal. Time has proved to be his most effective defense.

For Nazi hunters and European prosecutors, Kalymon’s death outside Detroit last month at the age of 93 represents a lost opportunity to prosecute one of the Holocaust’s suspected perpetrators, whose numbers shrink with each passing year.

Kalymon was reportedly wanted in Germany on suspicion of participating in war crimes during World War II.

His death was confirmed to the Los Angeles Times by his attorney, Elias Xenos, who added that Kalymon always denied the charges against him, which include allegations that he shot at and killed Jewish prisoners in one of Poland’s ghettos.

Kalymon’s son, Alex, told the Associated Press that his father died at home in Troy on June 29 after battling pneumonia, prostate cancer and dementia.

Perhaps one of the more surprising things about Kalymon’s death was that it occurred in the U.S., which had stripped him of his citizenship several years ago, opening the door for his deportation.

Kalymon had immigrated to the U.S. in 1949, part of a great wave of human displacement after World War II and during the dawn of the Cold War. He became an American citizen six years later.

American officials realized much later that Kalymon, who was born in Poland, had been a member of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, which served German officials and helped persecute Polish Jews.

Kalymon had lied about his job during the war when he immigrated, according to court documents.

Kaylmon was a police officer in the city of Lviv in present-day western Ukraine. In 1939, Lviv had more than 200,000 Jewish residents — before they were killed, deported or driven into hiding during the war, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police helped guard and search for Jews, who were shot if they resisted, according to court records. Ammunition was in short supply during the war, so each time officers fired their weapons had to be documented, the court records say.

Police records say that a guard with Kalymon’s name repeatedly fired his gun while guarding Jewish captives, with one record saying that he killed at least one captive. Other records noted that Jewish captives had died on the same days that Kalymon and other officers recorded firing their guns.

On these grounds, the U.S. filed a complaint in 2004 to strip Kalymon of his American citizenship, a common tactic used against suspected Holocaust perpetrators living in the U.S., which has no jurisdiction over war crimes committed in Europe during the war.

In a bench trial, Kalymon said he had joined the police in 1941, when he was 20, out of a “necessity to survive” during the war. He denied persecuting Jews, denied firing shots and said he lied about his service when immigrating to the U.S. because he was afraid of being deported to Soviet territory.

“He was the lowest-ranking member” of the police force, his attorney, Xenos, told The Times, also disputing the gunshot records. “He worked there to make a living, and his position was that he was guarding a sack of coal from looters — that was his job.”

But a federal judge disagreed, finding that the documents were convincing evidence.

In conjunction with a finding that Kalymon lied about his service in the auxiliary police when immigrating to the U.S., the judge revoked Kalymon’s American citizenship in 2007.

Kalymon was never deported to face trial in Europe, however.

After Kalymon was denaturalized, U.S. court records showed that Polish prosecutors had expressed interest in questioning Kalymon, and proscutors in Munich, Germany, had filed an arrest warrant against Kalymon earlier this year, according to the AP.

The AP also reported that German officials had hoped to send a doctor to the U.S. to examine Kalymon to determine whether he was physically fit for trial. But his attorney, Xenos, told The Times that his client was already in failing health.

“He had cancer, and over the last year before his death, he basically — I don’t know if he had Alzheimer’s — but he definitely wasn’t mentally competent,” Xenos said, adding that Kalymon had been “among the last” Holocaust suspects living in the U.S.

Just last month, U.S. officials arrested former Auschwitz guard, Johann Breyer, 89, who was living in Philadelphia. Breyer will face proceedings in August for extradition to Germany, where he faces Holocaust-related charges.

Breyer’s prosecution could be among the last of its kind, as many Holocaust suspects have died, like Kalymon, or have gotten too infirm to prosecute.

In an interview with The Times for that story, Aaron Breitbart, a senior research for the Simon Wiesenthal Center, said it is common for defense attorneys to slow down proceedings for surviving suspects to achieve “biological amnesty.”

In other words, to put off trials for so long that defendants die before they face a jury.

Follow @MattDPearce for national news

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.