Republican majorities struggle to get Congress working

- Share via

WASHINGTON — After six weeks in session and 139 roll call votes in a House and Senate that feature some of the largest Republican majorities in generations, one of the most telling statistics from the new Congress is this: President Obama’s veto threats outnumber the bills Congress has been able to send him.

When Republicans swept into power last November, they promised a new era of productivity and discipline that would break four years of gridlock. “America’s New Congress,” they called it.

But far from striking a bold contrast with the last two terms of stalemate, congressional Republicans have quickly run into familiar obstacles, including partisan paralysis and party infighting.

Friday, as members of Congress rushed to leave town on a bitterly cold morning, Republicans celebrated their most visible accomplishment to date: sending the Keystone XL pipeline bill to Obama’s desk for his expected veto.

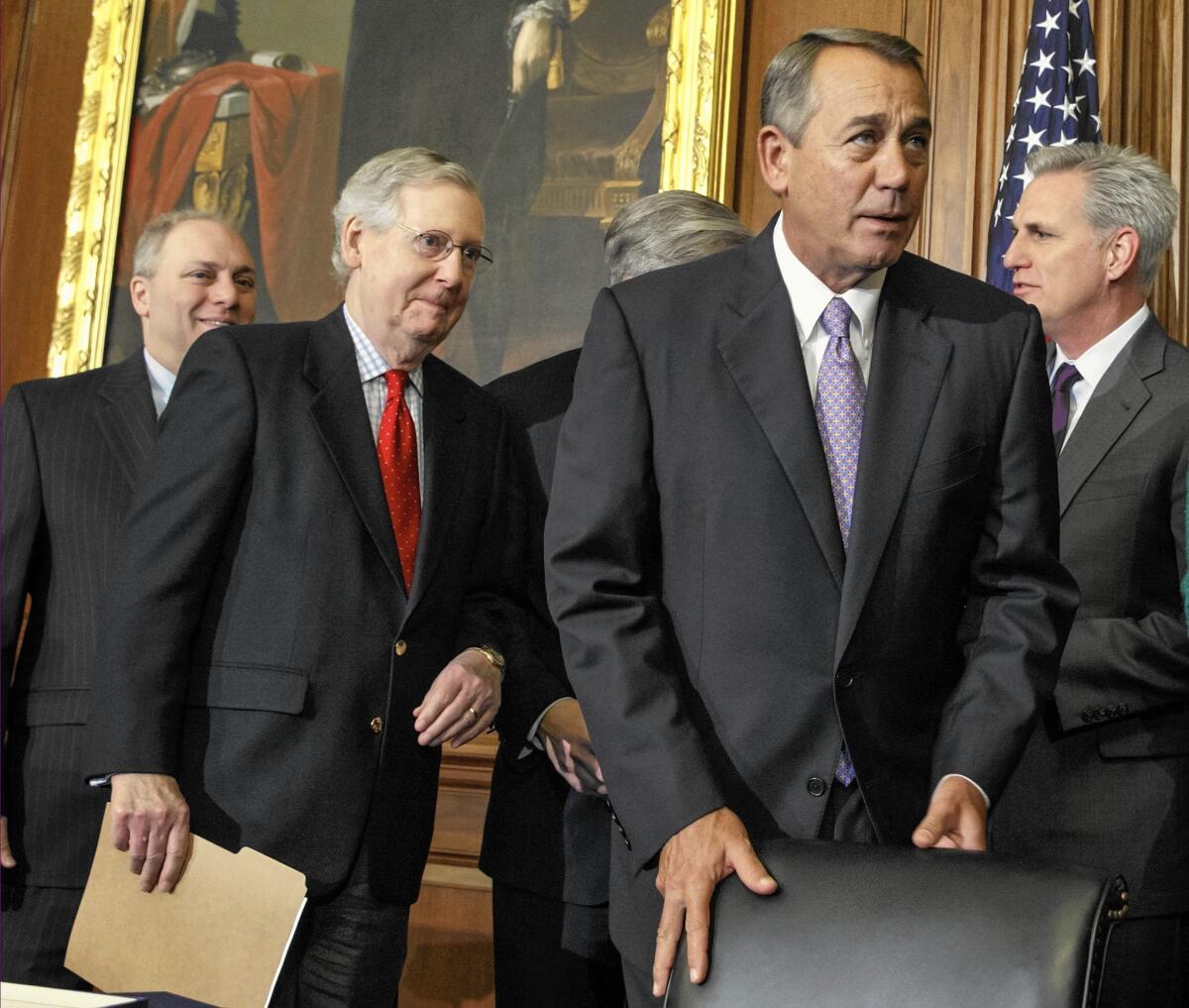

“To the president I would say this: Do the right thing, sign this bill and help us create more jobs,” House Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio said in brief remarks before affixing his signature to the legislation.

But as members of Congress go home for their first extended break since Republicans took control Jan. 6, they have few other achievements.

Only two bills have become law — one a leftover from last year that funds a terrorism insurance program important to real estate developers, the other a noncontroversial measure to address mental health problems among veterans.

That compares with six new laws at this point in 2007, when Democrats came to power in both chambers for the final two years of President George W. Bush’s tenure.

The new Republican majority, said one lawmaker granted anonymity to speak openly about their work, is like the dog that caught the car — still figuring out what to do next. Rather than begin the year with an agreed-upon strategy or comprehensive agenda for the party in power, the 114th Congress opened last month with a loosely defined set of legislative priorities.

Even the Keystone bill was passed only after an exhaustive process in the Senate. During the course of the debate, more amendments were discussed and dispensed with than in the entire previous year when Democrats were in charge.

In the meantime, however, gas prices plummeted, leaving some analysts to question whether the pipeline project would still pencil out.

“Is it the most important piece of legislation facing the nation? No. But it is an opportunity for us to prove that we’re able to work with each other and govern, and it is a good test of whether or not the president is interested in doing that as well,” said Rep. Mick Mulvaney (R-S.C.). “We have to learn how to crawl before we can walk, and walk before we can run.”

They’ll have to walk quickly. When lawmakers return to Washington in a little more than a week, they’ll once again face something Republicans had hoped to leave behind them — the possibility of a partial government shutdown.

The shutdown threat stems from a legislative trap Republicans set for themselves last December after Obama moved to shield up to 5 million people in the country illegally from the possibility of deportation. At the behest of conservatives eager to undo the new policy, lawmakers agreed not to fund the Department of Homeland Security, which handles immigration among other duties, past Feb. 27.

Republican leaders struggled for most of the last six weeks to find a way forward before the Homeland Security money runs out. They initially hoped a few Senate Democrats who have qualms about Obama’s immigration plans might join them on a bill that would fund the department and overturn the president’s executive action.

But Democrats have remained united in blocking any such plan. Republicans, with 54 senators, would need six Democrats to break ranks to end a filibuster of the bill.

The party’s disarray about what to do next could be seen over the last several days as Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) exchanged barbs over who was to blame for the impasse.

Some Republicans in the House suggested their Senate counterparts overturn the chamber’s filibuster rules to get the bill through.

“We understand what the math is. But they have procedural rules that they can change,” said Rep. Raul R. Labrador (R-Idaho).

Senate Republicans, who had angrily objected when Democrats did away with the filibuster for confirming most nominations, immediately shot down as unworkable the idea of wiping out legislative filibusters as well.

Internal Republican disagreements have flared along other traditional fault lines, such as abortion, derailing bills that the GOP leadership had hoped would notch some early victories.

The House has passed dozens of bills in its six weeks, including a repeal of Obamacare as well as measures on taxes and abortion.

House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) wrote to colleagues Friday. He trumpeted the “unprecedented” output and noted that many of the bills drew bipartisan support.

“Despite a few detours along the way, we should be proud of what we’ve accomplished,” he wrote.

Many of those bills, however, mirror measures that passed in the last Congress only to collect dust in the Democratic-controlled Senate. House Republicans have hoped that their proposals will do better with Republicans in the Senate majority for the first time in eight years.

So far, however, McConnell has seemed more concerned with restoring a more freewheeling but slow-moving legislative grind than with delivering legislative victories.

Even when Republicans have been able to stick to their shared priorities — approval of the Keystone legislation, for example — they are running into the power of the White House veto threat.

But all along, Republicans have said they should be judged not by their debut, but by the next few months of grueling legislating.

April, when the party plans to pass its annual budget blueprint, will be the crucial point, party leaders say. The budget, they say, will provide a repudiation of Obama’s approach and a road map for their party’s candidates in the 2016 presidential election.

Rep. Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.), the party’s former budget guru and now head of the House’s powerful Ways and Means Committee, outlined an ambitious agenda Friday as part of Republicans’ plan to provide alternatives to Obama’s approach on healthcare, tax policy and entitlement programs.

When asked to assess the new Congress’ performance so far, the former vice presidential nominee suggested the outcome was incomplete.

“We’ve got a lot more to come,” Ryan said. “I feel like we’re just hitting our stride.”

Twitter: @mikememoli, @lisamascaro

ALSO:

In Republican Congress, two divergent strategies at work

GOP congressional majority likely to change way it crunches numbers

House abortion bill switch reveals emerging clout of moderate Republicans

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.