Standing Up: Davien’s Story

- Share via

Wrestling with his fears

After the nightmares started, Davien Graham avoided his bicycle.

In his dreams, he pedaled his silver BMX bike through his neighborhood, heard gunfire and died.

If I stay off my bike, I'll be safe, he thought.

He placed it in a backyard shed, where it sat for months. But Jan. 12, 2008, dawned so spectacular that Davien decided to risk it.

He ate Cap'n Crunch Berries cereal, grabbed the bike and rode a half-mile west to Calvary Grace, a Southern Baptist church that was his haven.

| Advertisement |

| |

Davien lived with an unemployed aunt and uncle, a former Crip, and five other kids in a cramped four-bedroom house in Monrovia, about 20 miles east of Los Angeles.

Yet as a 16-year-old junior at Monrovia High School, Davien earned A's and B's, played JV football and volunteered with the video club. He cleaned the church on Saturdays for minimum wage.

If I live right, God will protect me.

That afternoon, sweaty from cleaning, Davien reached for his wallet to buy a snack — only to realize he had forgotten it at home.

After returning to his house, he caught his reflection in the front window. He was 6 feet 2 and wiry. His skinny chest was beginning to broaden. He was trying to add weight to his 160-pound frame in time for varsity football tryouts.

He showered, told his aunt he would be right back and again jumped on his bike, size-14 Nike Jordans churning, heading for a convenience store near the church.

At the store, he bought Arizona fruit punch and lime chili Lay's potato chips. He recognized a kindergarten-age Latino boy and bought him Twinkies.

Davien pedaled down the empty sidewalk along Peck Road. He could hear kids playing basketball nearby. As he neared the church, a car passed, going in the opposite direction. He barely noticed.

He heard car tires crunching on asphalt behind him. He glanced back, expecting a friend.

An X marks the spot where Davien Graham was shot. (Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department)

Instead he heard: "Hey, fool."

The gun was gray. It had a slide. Davien recognized that much from watching the Military Channel.

Behind the barrel, he saw forearms braced to fire and the face of a Latino man, a former classmate.

The gunman shouted, "Dirt Rock!," cursing a local black gang, the Duroc Crips.

Davien's mind raced: Don't panic. Watch the barrel. Duck.

Suddenly, he was falling. Then he was on the ground, looking up at the church steeple and the cross.

He heard more shots, but stopped feeling them. A chill crept up his legs.

Davien watched the sedan disappear down the street. He saw the boy he had bought the Twinkies for and other children spilling out of a nearby apartment building.

He was having trouble breathing. He felt sleepy.

He tried to raise his eyelids to see if the shooter was returning. He knew gangsters don't like to leave witnesses.

Davien was raised not to snitch.

He grew up south of the Foothill Freeway and Monrovia's quaint downtown, in a frayed, unincorporated area neighbors call No Man's Land.

The oldest of six children, he learned as a small boy not to feel safe anywhere. He played under the towering pines and sweet gum trees of Pamela Park, where gangbangers stashed guns in bathrooms and addicts left crack pipes in sandboxes.

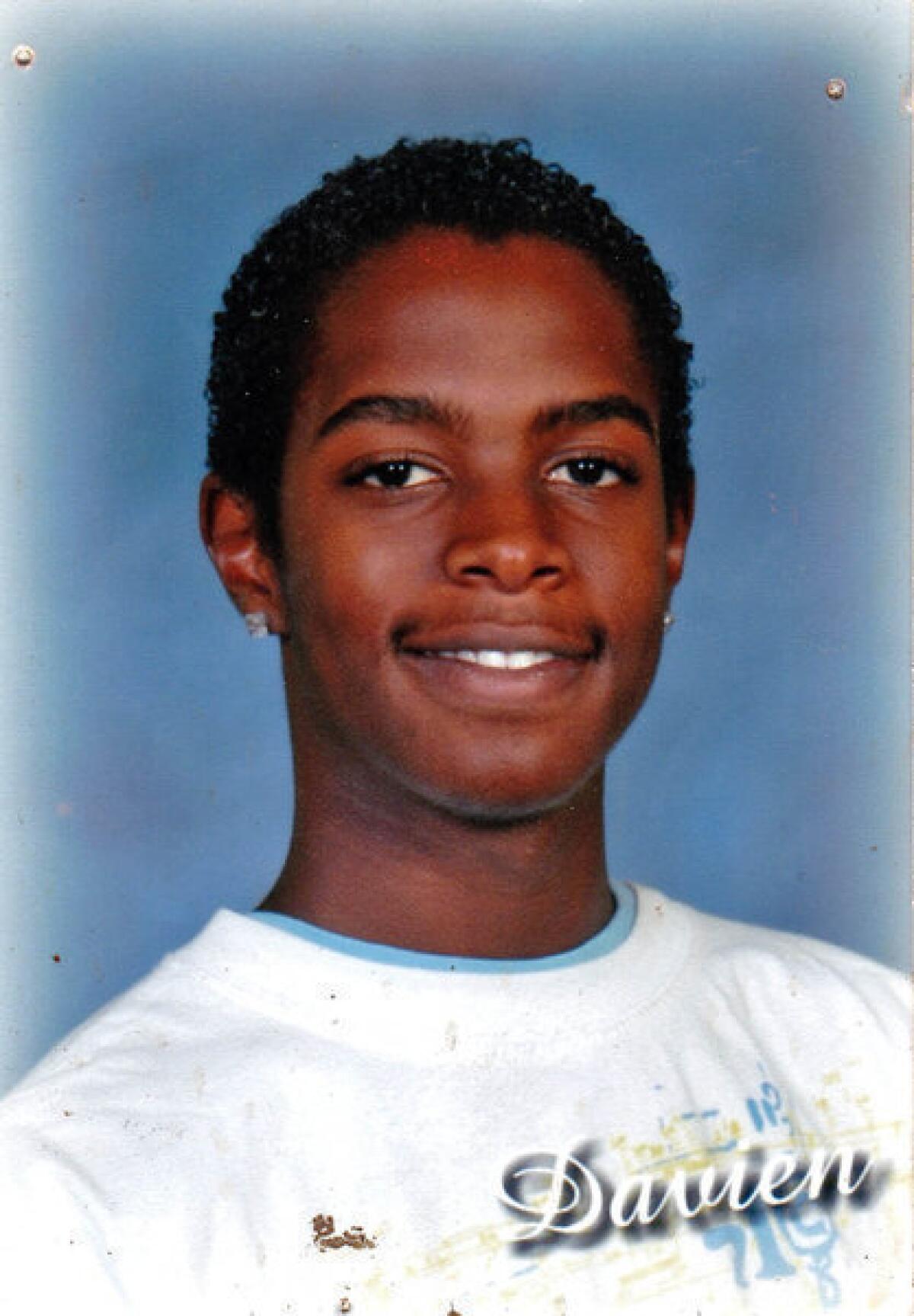

Davien in an undated school photo. (Courtesy of Davien Graham)

He witnessed his first drive-by when he was 4 years old. He came to recognize the sound, "like a loud drum, a thunderclap."

He grew leery of sedans with tinted windows, "drive-by cars," and gangsters who sprinted past his house and across "the wash," a drainage canal, with police in pursuit.

For Davien's safety, a relative had walked him to school — until he, too, was shot and his body dumped in the wash.

Davien had one goal in mind: to make it to his 21st birthday.

Drug dealers, bookies and hustlers called to him from the streets: "Hey, Day Day! You just like your dad."

The comparison made him cringe. Davien's father, Steven Graham, or Steve-O, was a Crip who pleaded guilty to cocaine possession weeks after Davien was born. Steve-O would spend several years in prison.

Afterward, on days Steve-O got high or drank too much, he would put on his sunglasses and take Davien out to the yard for lessons in manhood, often bringing a shotgun.

Davien's mother, Sharri McGhee, also struggled with drugs.

Even so, when times were good, Davien felt as though he belonged to a normal family. His mother would check them into an Embassy Suites hotel so they could swim in the pool. It felt like Disneyland.

Then he woke up one morning and all his videos and the TV and VCR were gone, and he saw his dad walking home because he had sold the car, too.

The best way to become a man is to look at those around me, and do the opposite.

By the time he started school, Davien had learned not to depend on adults for protection. He saw kids whisked away from their parents by the state, or sent to juvenile hall. He promised his younger brothers he would take care of them.

One day he found his pregnant mother lying on the back patio, convulsing. At the hospital, she delivered a premature baby girl with drugs in her system.

The state intervened. At age 9, Davien, two brothers and the baby were sent to live nearby with his aunt and uncle, Joni and Terry Alford, and their two children. Davien thought they acted more like big kids than parents.

The best way to become a man is to look at those around me, and do the opposite.

On Jan. 30, 2007, as Davien and his uncle walked in the neighborhood, they spotted a group of Latino men approaching, heads shaved gangbanger-style, arms covered in tattoos.

Suddenly, everyone was shouting in English and Spanish. Someone fired a gun.

His uncle stumbled off, shot in the calf.

Davien ran, hiding under a low brick garden wall. He could hear the strangers searching for him, their breath close. He wondered where his uncle had gone.

After they left, he bolted home, arriving to see paramedics lift his uncle into an ambulance. Sheriff's deputies followed.

His uncle answered some of their questions. But he never identified the shooter. He wasn't a snitch.

Deputies questioned Davien too. He knew he was supposed to tell the truth, as a Christian. But helping deputies would put his family at risk.

He didn't describe the suspects. No one was arrested.

Davien soon began having the nightmares about getting shot on the silver BMX his uncle had given him.

As Davien lay bleeding on the grass, he played dead.

Through droopy eyelids, he watched cars brake for a stop sign across the street, then zoom off. He recognized one driver, a neighbor who looked away.

She must think I'm a gangster.

A red Ford Explorer slowed, windows rolled down. Davien took a chance.

"Ma'am, I need help, I've been shot!" he yelled.

The car stopped and a white lady with long red hair and glasses jumped out. She grabbed Davien's hand and called 911.

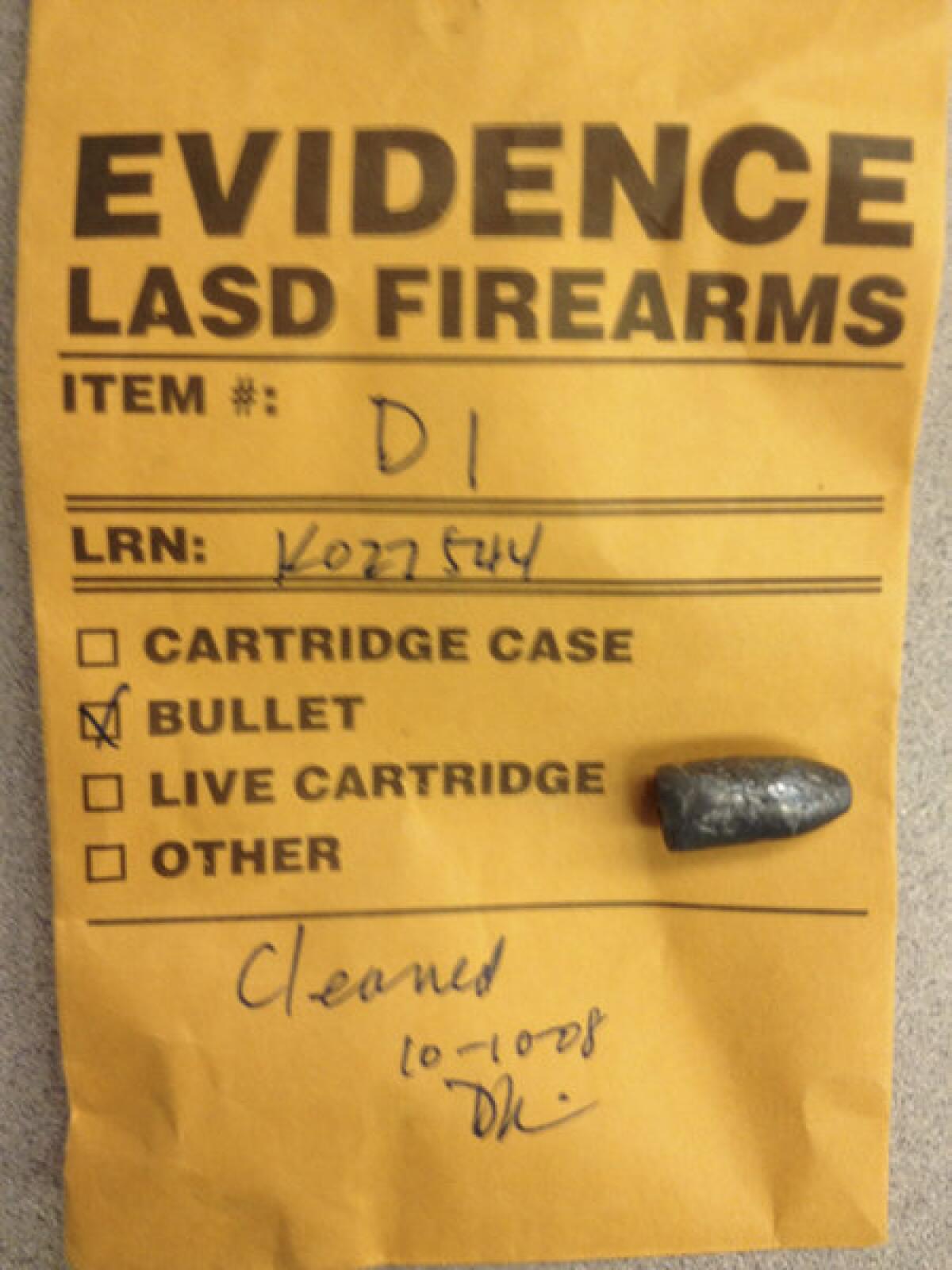

A bullet recovered by a surgeon from Davien’s body was later introduced into evidence. (Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department)

It was 4:57 p.m.

"There is a young African American gentleman who has been shot," the woman told dispatch. "There's a lot of children out here as well, if you can kind of hurry."

Davien groped for the cellphone in his pocket just as it started to vibrate.

It was his aunt. She and his uncle had been out on the front stoop and thought they heard gunfire.

"They shot me," Davien said. He hung up so his aunt could call 911.

His uncle soon pulled up in the family's white SUV. He cradled Davien's body.

"I can't move my legs!" Davien cried, loud enough for the 911 operator to hear.

His uncle grabbed the church's water hose and held it to Davien's lips. Davien stared up at Calvary Grace.

I don't want to die.

He felt himself passing out, eyes rolling back into his head. He gripped the grass beneath him. His uncle was shouting his nickname.

"Day Day, come on!"

Paramedics arrived and loaded Davien into an ambulance. Just then his aunt rushed up. She was an imposing figure, heavyset, with tattoos and a deep voice. Los Angeles County sheriff's deputies stopped her.

Had Davien belonged to a gang, they asked?

His aunt pointed to the church. Go ask somebody in there, she said as she climbed into the ambulance. Church folks would set them straight, she figured.

A block away at the convenience store, a witness called 911. She told the operator she saw three or four people flee in a black Nissan.

“I heard the pop, pop, pop… I didn’t want them to see I saw them.”—Witness

"I heard the pop, pop, pop. I turned, I didn't want to look at the vehicle, I didn't want them to see I saw them."

"Did you actually see them do it?" the operator said.

"Yes, I did."

"Are you going to talk to deputies?"

She paused.

"I'm a little concerned," she said, her voice quavering. "I'm a little bit worried, too, for my safety and for my kids."

By the time detectives interviewed her, the woman insisted she had not seen the shooter.

That left Davien as the only witness.

Davien awoke in intensive care. He didn't know what day it was. He couldn't tell if the sun was rising or setting.

A thick zipper of a scar sealed his chest. A tube jutted from his stomach, another from his arm. A ventilator covered his mouth, making a Darth Vader sound. He had trouble staying awake.

Below his waist, he felt nothing.

Doctors told him he was at Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, listed under a fake name as a precaution. He had been shot twice, in the left flank and right buttock. One bullet lodged in his ribs, another splintered.

Surgeons had labored for five hours to patch his left lung, remove his left kidney and his spleen. They could do nothing to repair his L1 vertebra. His legs were paralyzed.

A nurse brought pad and pen. Davien wanted to tell his family about the shooting. He had recognized the shooter, but he was too scared to write down a name.

Instead, he scribbled: "I forgive them."

Days later, Sheriff's Det. Scott Schulze showed up at Davien's bedside with a series of mug shots.

Davien spotted the shooter immediately. Jimmy Santana had taken gym classes with him in middle school and later joined a Latino gang, Monrovia Nuevo Varrio, or MNV.

The detective asked Davien if the shooter was among the photos.

Davien feared what could happen if he snitched. He also believed as a Christian that it was wrong to lie.

He circled Santana's photo. Beside it he wrote: "It's him."

He was scared. And not just for himself.

Davien's younger brothers looked a lot like him.

Seventeen days after the shooting, on Jan. 29, 2008, deputies arrested Santana at his mother's house in Duarte. He would stay in jail until a preliminary hearing to determine if he should stand trial.

Investigators believed Davien was the victim of a 17-month war between black and Latino gangs, dating to a night when Latino gang members went gunning for Vincent Minor, a black Duroc Crip associate.

About 10 p.m. on Aug. 9, 2006, suspected members of Duarte Eastside, a Latino gang, arrived at Minor's ranch house.

The gang sprayed the house with bullets from a 9mm handgun. One pierced a converted garage, killing Minor's father, 54-year-old Michael Minor, who volunteered as a youth football coach.

Payback came within hours.

Three outraged Duroc Crips spied a Duarte Eastside gang member, Marcus Maturino, sipping a beer outside a house on Shrode Avenue, less than a mile from the first shooting.

The Crips fired with a .45 and a TEC-9 handgun. They missed.

Standing nearby was Nicole Kaster, an aspiring gym teacher. A bullet struck her in the face, killing her. She was 22.

Tit-for-tat retaliation followed — with 71 gang-related shootings by the end of 2007. Investigators struggled to make arrests. Witnesses disappeared, changed their stories or clammed up.

In June 2007, members of Monrovia Nuevo Varrio strode up to a black crowd at a park and opened fire, wounding one person.

Police arrested Santana and charged him with four counts of assault with a semiautomatic firearm. Later, a judge dismissed that case against him for lack of evidence.

Santana, 18, lived at home with his mother and older brother, a gang associate. Santana had been nicknamed Lil Tuffy by the gang and inducted into a clique called the Pee Wee Locos. On a bedroom wall, he had tacked an ode: "Enemies run from me, they're all cowards, because I'm the shot caller with lots of power."

On Dec. 12, a month before Davien was shot, two black men shot and killed 24-year-old Hector Acosta as he rode his motorcycle on Millbrae Avenue in Duarte. Acosta wasn't a gang member.

Everyone knew what would come next: MNV would retaliate. This time, they would send a gangster who knew how to hit a target and could be trusted not to talk if he got caught.

Davien was in the hospital for eight weeks, undergoing multiple surgeries. He tried to puzzle out why God let him get shot.

His faith wavered. He began to doubt the wisdom of testifying against Santana.

On March 14, 2008, two months after the shooting, Davien was discharged. He returned to his aunt and uncle's house in a wheelchair.

He was a wisp of his former self, 70 pounds lighter. Bones in his toes were brittle; doctors warned that if he ran into something in the chair, they could shatter.

In the weeks after he was shot, Davien was treated at Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, where he underwent physical therapy as he adjusted to life in a wheelchair. (Barbara Davidson/Los Angeles Times)

Surgeons had removed the bullet from his ribs, but they could do nothing about the fragments near his spine. Hot fingers of pain yanked him awake at night, tugging the breath out of him.

God, give me just five minutes without it.

Davien was scheduled to testify at Santana's preliminary hearing four days after being released from the hospital.

He couldn't decide what to do. He worried that every approaching car might bring another drive-by. In a wheelchair, it would be hard to flee.

Relatives offered little help. Some were scared of being attacked; others were bent on revenge. Few trusted the police.

Davien returned to church looking for answers. On Palm Sunday, two days before Santana's hearing, he entered the sanctuary with his aunt and uncle.

He tried to listen to the sermon but he couldn't concentrate. His spine was throbbing again.

His uncle wheeled him out to the church parking lot.

You need to face your fear, his uncle said.

He started pushing Davien toward the front of the church, the site of the shooting.

His aunt joined them, followed by the pastor's wife.

They crept forward. When they reached the sidewalk, their pace turned glacial.

"OK to go further?" his uncle asked.

Davien’s uncle, Terry Alford, wheels him back to the scene of the shooting, urging him to confront his fears. (Barbara Davidson/Los Angeles Times)

Davien reluctantly nodded.

His aunt sobbed. The pastor's wife held her.

Staring down that barren road, walled off by backyard fences, Davien saw himself back on the grass, bleeding.

He knew three people who had been gunned down in the Monrovia area since he was shot: a 16-year-old girl killed next to the church, a 19-year-old former Duarte High School football player and a 64-year-old man. None was a gang member.

If Santana could shoot me here, he thought, he could shoot anyone anywhere.

Davien couldn't stand. But he could stand up.

"OK," he told his uncle. "I'm straight."

Wrestling with his fears

After the nightmares started, Davien Graham avoided his bicycle.

In his dreams, he pedaled his silver BMX bike through his neighborhood, heard gunfire and died.

If I stay off my bike, I’ll be safe, he thought.

More...

Making peace

A whirring mechanical lift raised Davien Graham’s wheelchair to the witness stand in Department X on the fourth floor of the Los Angeles County courthouse in Alhambra.

Pain burned at the base of Davien’s spine. Then his eyes met Jimmy Santana’s for the first time since the shooting.

More...

Tit-for-tat gang retaliation

Davien's journey

Photos by Barbara Davidson

Making peace

A whirring mechanical lift raised Davien Graham’s wheelchair to the witness stand in Department X on the fourth floor of the Los Angeles County courthouse in Alhambra.

Pain burned at the base of Davien’s spine.

His eyes met Jimmy Santana's for the first time since the shooting. He thought Santana seemed much smaller sitting at the defense table than he had with the gun in his hand. In his baggy blue jail uniform, he looked like a child.

Two months earlier, on Jan. 12, 2008, Davien had been gunned down as he rode his bike in front of his church, a bystander in a gang war that had raged in Monrovia for two years.

| Advertisement |

| |

He recognized Santana as the shooter. They had gone to school together. Still, Davien was afraid to identify him to police. He had been raised by a father and an uncle who were Crips, who taught him that victims don’t snitch.

But Davien had shunned gangs for a Christian life, and believed lying was wrong. So when asked by detectives, he had circled Santana’s photo in a lineup of mug shots.

Now he was being asked to set aside fears of retaliation and testify.

Staring at Santana, Davien said the first thing he remembered telling his family after the shooting was, “I forgive the person who did this to me.”

Santana stared back, appearing unmoved.

Sitting in his wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down, Davien could see Santana’s mother in the gallery, a small woman with a strained face. A group of young people lounged behind her.

Maybe they were in the car with Jimmy that day.

Police never caught the getaway driver.

The prosecutor asked a question, addressing Davien as John Doe, an effort to protect his identity. It didn’t matter. Everyone involved in the case knew Davien.

“Do you see the man who shot you here in court today?”

“On the right side of the courtroom, and he’s wearing a blue uniform,” Davien said.

That was all the judge needed to hear. He ordered Santana to stand trial. Davien was free to go.

But he didn’t feel free.

They must think I’m a gangster and was shot as payback.

As Davien left court, the judge ordered two deputies to escort him to the parking lot, just in case.

Davien knew his biggest hurdle lay ahead; testifying at Santana’s trial.

As the case dragged on, Davien felt like he was doing time, waiting. He began to believe that his aunt and uncle, Joni and Terry Alford, resented caring for him, especially when he bumped into their furniture or peed in his shabby wheelchair.

They didn’t seem to fear for his safety. Sometimes when they ran errands, they would leave him alone in the car, feeling trapped and exposed.

Davien wanted to put the trial behind him. He wanted out of Monrovia. He decided the best way out was to finish high school and make it to college.

It took months for Davien to regain strength. He returned to Monrovia High for his senior year. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

In September, he returned to Monrovia High; back among his friends, he thrived. He almost forgot about the trial. Then one day some guys drove by his house, shouting threats. It wasn’t clear if the message was meant for Davien or for his uncle.

Some time later, Davien was called to the principal’s office. Sheriff’s deputies were waiting.They told him they had intercepted a threatening message in gang code at the county jail. He apparently was being targeted.

We’re taking you home to grab some things, deputies said. You can stay in school, but not with your family. You’re being relocated.

Back at the house, his aunt watched him pack. Deputies could not say where he was going, or for how long.

“It’s messed up,” Davien said, trembling. “Not only did he take my legs away from me, now he’s trying to take my whole life.”

Deputies took Davien to stay with a teacher the officers knew.

Davien felt safer. But he still worried, especially about his brothers at home. One of them had started working at Calvary Grace, the church where Davien had been shot.

Over the next three years, as the sheriff’s task force tamped down the gang war, Davien’s case passed to a new public defender, a new prosecutor and six different judges.

Davien graduated from high school and moved from Monrovia to attend college in Fullerton. He learned to get around in his wheelchair, and had more surgeries than he could remember to deal with the bullet fragments inside his body.

One day last fall, as he was preparing for exams, Davien arrived at his apartment to find sheriff’s deputies and a detective he had grown to trust, Scott Schulze. The trial was starting Jan. 26, 2012. They handed him a subpoena. He was startled and upset.

He had agreed to testify. Why were they acting like they had to force him, surprising him at his apartment with his friends?

Davien called the new prosecutor. He didn’t trust her, so he recorded the call. He asked why she hadn't come to see him herself and why she sent deputies when she knew he had agreed to show up.

She didn't sound apologetic, he thought.

He hung up feeling like he was heading to court without anyone on his side.

Davien could feel jurors’ eyes crawling over his face. He stared ahead, focusing on the prosecutor, just as Schulze had recommended.

Davien, by then 20, shifted in his wheelchair on the stand, looking down at the gallery. He recognized Santana’s mother. She and another son testified that Santana was home with them at the time of the shooting. It was their word against Davien’s.

Los Angeles County Sheriff's Det. Scott Schulze, whom Davien had come to trust, escorts him into court as he prepares to testify. (Barbara Davidson/Los Angeles Times)

No one from Davien’s family was there. He didn’t tell them about the trial because he didn’t want to put them at risk if gang members showed up.

He tried to clear his throat; his mouth was dry. In a court system handling more than 1,800 attempted murder cases at the time, 600 of them gang-related, he felt lost.

He hoped the jurors could read him, the way parents read a child. Jurors needed to see that he was no gangster. He just happened to be young and black and in the wrong place.

Surely the lone black juror, a woman staring at him from the front row, would understand.

Santana, 23, sat 15 feet away, slouching into a baggy dress shirt.

The prosecutor asked Davien to demonstrate how his attacker pointed the gun.

Davien extended his willowy arms, clasping his hands in the shape of a pistol. He winced. His back ached every time he bent his 6-foot 4-inch frame to the microphone.

“Where was it being pointed?” the prosecutor asked.

“At my face.”

He could feel sweat spreading under his arms, wilting the new button-down shirt he bought at Target for the trial.

“Did you see anyone in the car?” she asked.

“I saw a driver and a passenger,” Davien said, without looking at Santana.

“Did you know who said ‘Hey fool’?”

“The passenger,” he said.

“Did you get a look at the passenger?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Now Davien glanced at Santana. The accused was biting his shadow of a mustache.

“Did you see his face?” the prosecutor asked.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Can you look around the court and see if the person is here?”

Davien did not hesitate.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Candace J. Beason looks at Jimmy Santana as Davien points at him and explains that Santana shot him. (Barbara Davidson/Los Angeles Times)

“Yes, ma’am,” Davien said, “He is sitting next to his lawyer in a collared shirt.”

“How confident were you that he was the person?”

“One hundred percent.”

Not long afterward, Santana’s public defender stood. Davien had once imagined himself looking just like that lawyer: a black man standing tall in an elegant suit.

What was the name of your uncle’s former gang, the lawyer asked.

Davien frowned. “I don’t recall.”

“You don’t recall what gang?”

The prosecutor objected. The judge overruled her. Davien had to answer the question.

“He was a Crip,” Davien said.

Jurors shifted in their seats. Davien feared they were souring on him. They didn’t know how hard he had tried to live right.

They think I got shot for a reason.

At 3:50 p.m. on Feb. 2, after six hours of deliberation, a buzzer sounded signaling a verdict.

The bailiff brought Santana into the courtroom. His mother bowed her head and grasped the hand of her other son, praying in a whisper of Spanish, “Let it be just.”

For added security, four more bailiffs slipped into the courtroom.

As the clerk read the verdict, Santana shook his head.

Jimmy Santana reacts to the jury's verdict: guilty on all counts. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Guilty on all counts, including willful, deliberate and premeditated attempted murder.

Santana sobbed, curling into himself. In the gallery, his mother was weeping.

Jurors filed out, eyes darting, avoiding the Santanas and searching for the polite young man in the wheelchair whom they would later say they believed from the moment he took the stand.

But Davien had gone back to school.

He would later send a statement for the prosecutor to be read to Santana at his sentencing in June.

The shooting broke him, Davien wrote. But he managed to recover and start a new life.

“I hope that you can become a better person during this whole experience,” he wrote to Santana. “Life does not end here for you. You can still do good to the world.”

Santana and his family declined to be interviewed for this article. He was sentenced to 40 years to life.

A month and a half after the trial, on March 17, 2012, Davien was surrounded by a crowd at his apartment. It was his birthday. He had fulfilled his childhood dream: survive to age 21.

Davien belted out a rap song he had composed.

“What do you see when you look in the mirror? Does it fade away or all get clearer?”

Davien’s father, Steven Graham, or Steve-O, was in the crowd. Steve-O had straightened out. Davien made peace with him and his mother—but as friends, not as parents. He had been his own parent for a long time.

Davien had a new goal. He was finishing his third year of college, planning to graduate with a degree in video production.

School can take me places that walking can’t.

He had fulfilled his childhood dream: Survive to age 21.

He has a five-year plan, which includes self-producing two rap albums from his mix tapes; “Musical Chair” and “Ramps and Elevators.”

He wants to produce a clothing line featuring a stylized handicapped logo, an after-school program for at-risk youth and a screenplay titled, “Where There’s Wheels, There’s a Way.”

At the party, his girlfriend presented a marble sheet cake decorated with his planned album cover: a photo of Davien in his wheelchair.

“It’s not every day a young man turns 21,” his father said. “You’re grown for the rest of your life—don’t turn back.”

He handed Davien a flute of pink champagne. Davien sipped slowly. Leaning forward to blow out his candles, he made a wish.

"Did anybody see who shot him?"

"Did anybody see who shot him?"