Senate approves modest filibuster changes

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Senate approved changes to the filibuster Thursday night, adopting modest limits on the partisan obstruction that has ground action in the chamber to a near standstill.

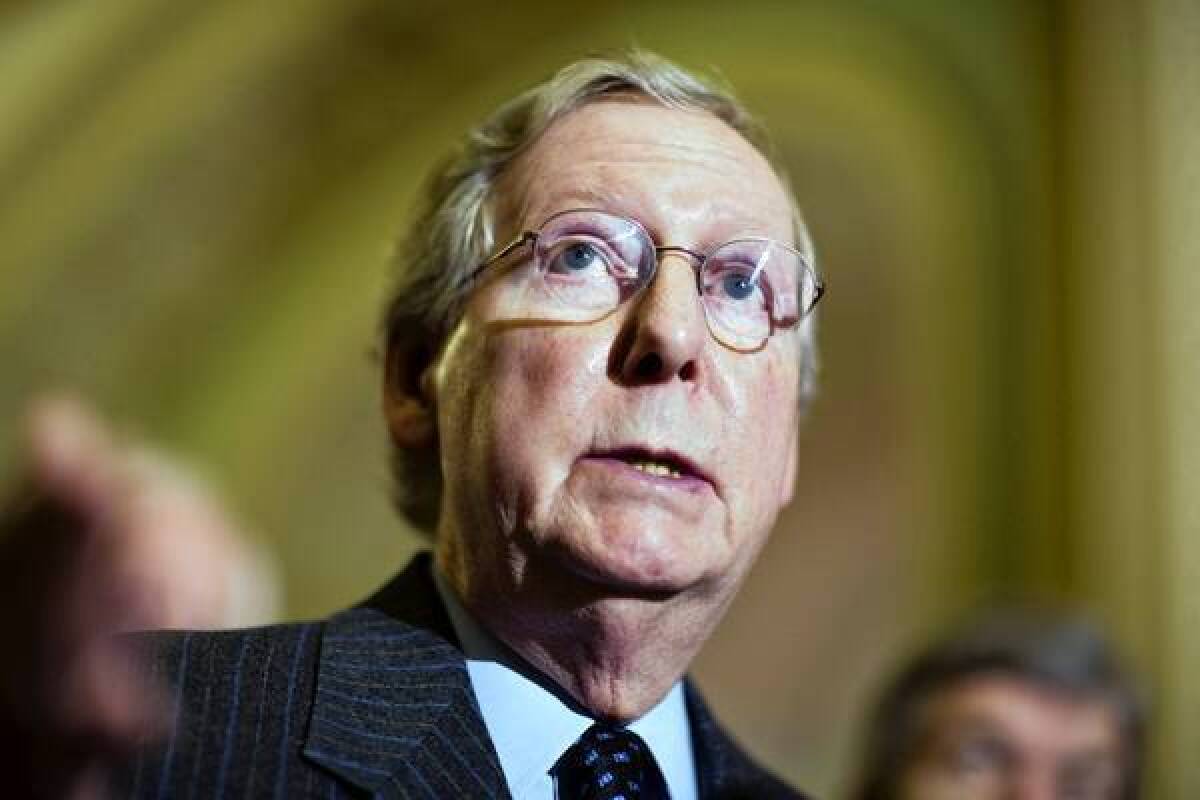

But the deal reached between the Senate’s two leaders — Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) — fell far short of sweeping reforms sought by liberal senators and their allies. Left out was the requirement that senators who want to filibuster must remain on the Senate floor, talking the whole time, as Jimmy Stewart’s character famously did in Frank Capra’s movie “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.”

The Senate adopted two packages to alter the procedural rules increasingly employed to thwart legislation and White House nominees. One provision will allow bills to be more quickly brought up for debate. Another will limit discussion on certain White House nominations. The changes were overwhelmingly approved, 78 to 16 and 86 to 9, with dissent mainly from conservative Republicans.

“It’s not everything I wanted,” said Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.), who led efforts to change the filibuster with Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.). “This is a small step, but it’s a step that moves us in a better direction.”

The last few years have seen skyrocketing numbers of filibusters in what has become an escalating procedural arms race. In recent years, Republicans, seeking to block Democrats from pursuing their agendas, have relied heavily on the tactic. In previous years, Democrats employed the filibuster to obstruct President George W. Bush.

A filibuster ties the chamber in knots because it only comes to an end with a 60-vote supermajority, which has proved difficult to achieve with a closely divided Senate in this partisan era. Even if that supermajority is reached, procedures require at least three days for each filibuster to be overcome.

“Too often over the past four years, a single senator or a handful of senators has been able to unilaterally block or delay bipartisan legislation for the sole purpose of making a political point,” President Obama said in a statement after the vote. “I am hopeful that today’s bipartisan agreement will pave the way for the Senate to take meaningful action in the days and weeks ahead.”

Democrats could have used their Senate majority to ram through a rules change at the start of the new Congress — or any time during this session. But they hesitated to provoke McConnell, a shrewd operator who would surely have retaliated.

“It just would have been thermonuclear war,” said Jim Manley, a former top aide to Reid who is now a Democratic strategist.

The agreement forged between Reid and McConnell should help move legislation more swiftly in the ponderous chamber.

Senators gave up their ability to filibuster — or hold endless debate — on the procedural step required to take up legislation on the Senate floor. In exchange, both sides were guaranteed the right to offer two amendments to the bill — a particularly important provision for the minority Republicans, who say they are forced to filibuster because Reid prevents them from trying to amend bills with provisions Democrats dislike.

Although senators can still filibuster the actual bill, eliminating their ability to block this procedural step will cut days off the process.

Over the years, senators, many of whom are senior citizens, have reached a gentlemen’s agreement not to press the requirement that they remain on the floor talking to filibuster, as South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond once did for more than 24 hours straight during the battles over civil rights legislation.

One aspect of the “talking filibuster” will be implemented, however: Once the 60-vote threshold is reached to end a filibuster and begin voting on a bill, a senator who refuses to waive the required 30 hours of final debate will need to stay on the floor and keep speaking. But that provision was included as a gentlemen’s agreement, rather than an official rules change.

“The incremental ‘reforms’ in the agreement do not go nearly far enough to deliver meaningful change,” said a statement from Fix the Senate Now, a coalition of legal scholars and liberal activists that pushed for reforms. Others had wanted the Senate to do away with the 60-vote threshold completely, pointing to changes in 1975 that dropped the two-thirds supermajority requirement to 60.

Also approved was a provision to speed confirmation of most presidential nominees, who are routinely held up as leverage to extract other concessions from the White House.

If a nominee can clear the 60-vote threshold to end a filibuster, debate time will be reduced from 30 hours to two for district court judges and to eight hours for sub-Cabinet positions. The lower limits would not apply to nominees for the Cabinet or higher courts.

Another provision reduces the number of filibusters that can be used to delay a conference committee, which is needed to reconcile differences between House- and Senate-passed bills.

The filibuster has been a storied part of Senate history, and the ability to cut off debate with a supermajority did not come about until 1917. Veteran senators have been hesitant to change the rules of the Senate, a chamber the forefathers designed to move more slowly than the fiery House.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.