A farming village older than the pharaohs

- Share via

Archaeologists have discovered the oldest known farming village in Egypt, a 7,000-year-old site whose residents grew wheat and barley and raised sheep, goats and pigs.

Farming probably occurred much earlier in Egypt, experts agree, but those first settlements would most likely have been along the banks of the Nile River and would have been obliterated by the periodic flooding and course changes of the river.

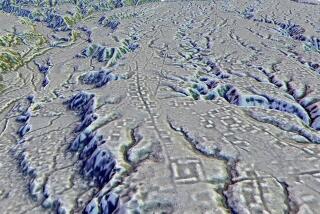

The site, in the Fayoum Oasis about 50 miles southwest of Cairo, was protected from such damage, and the discoveries show an agricultural technology in full bloom.

“This area is giving us a snapshot of what life was like” in Egypt more than 1,000 years before the Pharaonic and pyramid-building era began, said archaeo-botanist Melinda Zeder of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the research.

“We have a much richer record than anyone could have guessed,” she said.

The discovery by UCLA and Dutch archaeologists was announced Monday by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

The site has been heavily studied in the past, beginning in the 1920s with work by one of the first female archaeologists, Gertrude Caton-Thompson. She found well-preserved wheat and barley in granaries and dated them to about 5200 BC.

But neither she nor any of the researchers after her found any evidence of habitation, leading some researchers to speculate that the oasis might have been a summering grounds for nomads who traveled widely through the region.

The problem is that most of the remains in the oasis have been uncovered by blowing sand, leaving few artifacts in their original setting, said archaeologist Willeke Wendrich of UCLA, who led the research. Moreover, much of the area is, ironically, being trampled by modern agriculture.

At the end of the 2006 digging season, Wendrich’s team sunk a borehole into one sandy site previously excavated by Caton-Thompson and discovered subsurface evidence of bone and other artifacts. Before leaving, Wendrich managed to lease the six-acre site for a year.

When she and paleo-botanist Rene Cappers of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands returned last year, they found that the investment was worthwhile.

“What we have found here is a window into the development of agriculture” in Egypt, Wendrich said.

None of the remains of domesticated plants and animals were native to Egypt. All were originally domesticated in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East about 11,000 years ago and developed into a technology “package” over the succeeding 2,000 years.

The findings at Fayoum suggest that the technology was imported intact rather than invented locally, experts said. That possibility is supported by the discovery at Fayoum of a bracelet made from shells found only along the Red Sea, indicating that trade was occurring throughout the region.

Although the early results are not definitive, the findings so far suggest that this was an established year-round settlement. One key finding is the presence of pigs, “which is not an animal you would associate with people who were more nomadic,” Zeder said.

The team also found a much broader variety of fish bones than had previously been observed in the area. That suggests the inhabitants of the village had more sophisticated fishing technology than simply going out and using their hands to trap fish left behind in pools as the waters of Lake Qarun retreated seasonally, Wendrich said.

That also argues for a permanent settlement.

In further research at the site, which is protected by the Egyptian government, Wendrich hopes to be able to show at what time of year each of the food resources was used, which should provide definitive evidence for whether the settlement was seasonal or permanent.

The researchers also hope eventually to show how the farming technology arrived in Egypt.

On the northern side of the Mediterranean, evidence suggests that farming technology was spread by seafaring colonists who set up farming enclaves along the shores, from which the technology diffused to local peoples, Zeder said. But in Africa, she added, “we really don’t know.”

The research was supported by the National Geographic Society, the two universities and private donors.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.