For first time, researchers report some AIDS vaccine success

- Share via

More than a quarter-century after scientists discovered the virus that causes AIDS, researchers have finally shown that an experimental vaccine can block at least some infections, marking the first small but significant step toward eventual control of this lethal pandemic.

The benefits of the vaccine were modest, only a 31% reduction in the number of new infections. But coming on the heels of previous vaccine studies that either showed no benefit at all or actually increased the risk of contracting the disease, the study buoys the hopes of researchers who had nearly given on ever finding an effective way to block the spread of the virus.

The results were released overnight in Bangkok, Thailand, where the research was conducted by a team including Thai researchers, the U.S. Army and the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

“This is a historic day in the 26-year quest to develop an AIDS vaccine,” Dr. Alan Bernstein, executive director of the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, who was not involved in the research, said in a statement.

“We now have evidence that it is possible to reduce the risk of HIV infection with a vaccine,” said Mitchell Warren, executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, in his own statement. “There is little doubt that this finding will energize and redirect the AIDS vaccine field as all of us begin the hard work to translate this landmark result into true public health benefit.”

The trial, which began in 2003, had been disparaged by many critics as a waste of time and money because each of the two vaccines used in it had been shown in individual trials to produce no benefit. But researchers speculated that using them together, with one vaccine priming the immune system and the second boosting that response, would be more effective, and their optimism about this “prime-boost” combination has been validated.

Experts said that it will be many more years before a vaccine is available for wider use, but the results indicate at last that such a vaccine may, indeed, be possible. “It gives me cautious optimism,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which helped fund the study.

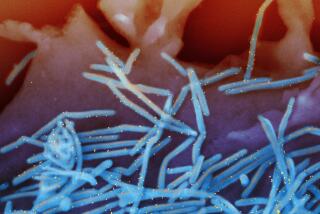

The primer in this combo is Alvac, made by Sanofi Pasteur, which uses a defanged canarypox virus to carry three synthetic HIV genes into the body. The boost comes from Aidsvax, originally made by VaxGen and now owned by the nonprofit group Global Solutions for Infectious Diseases. It contains a genetically engineered version of a protein from the HIV surface.

The study involved more than 16,000 volunteers in Thailand who had no unusual exposure to the virus, just the normal everyday risk. Half received four priming doses of Alvac and two boost doses of Aidsvax over a six-month period, and half received placebo shots.

After three years of follow-up, new HIV infections were observed in 74 of the 8,198 people who received the placebo, but in only 51 of the 8,197 given the vaccine, a statistically significant 31% reduction.

To the researchers’ disappointment, however, the vaccine did not reduce levels of HIV activity in those who became infected after being vaccinated.

Full details of the study will be released next month at a conference in Paris.

The vaccine was made using strains of virus that circulate commonly in Thailand, so it is not clear whether it would have any benefit elsewhere in the world. The manufacturers have not said whether they will attempt to license their products in Thailand.

At least 33 million people worldwide are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus, which causes AIDS, and 25 million have died, according to the World Health Organization. An estimated 7,500 are infected each day.

Aidsvax had failed in two large trials halted in 2003, showing no benefit to recipients. Another trial by Merck & Co. of a different vaccine was halted in 2007 when researchers found that the vaccine might increase the risk of contracting the virus.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.