Afghans Tell of Torture During Security Sweep

- Share via

DAI CHOPAN, Afghanistan — Villagers with broken limbs, deep cuts and severe bruises say Afghan militia fighters working as guides for U.S. troops went on a spree of looting, beatings and torture here during a military sweep last week.

The militiamen frequently guide the Americans on missions to search for Taliban and Al Qaeda guerrillas, wear U.S. military camouflage fatigues and carry assault rifles.

None of about 50 villagers who described the abuses in interviews, or who were questioned at an elders meeting, said U.S. forces witnessed the assaults or thefts during the search for Taliban guerrillas. A U.S. military spokesman said he had no reports of unprofessional conduct by militias operating under U.S. control.

But villagers here tell another story. Militiamen broke a woman’s shoulder with a rifle butt and tortured her two adult sons until they blacked out, one son said in an interview Saturday. The other son had not regained consciousness.

Others described assaults and systematic looting by the militia fighters during a weeklong operation in Dai Chopan. The militiamen, loyal to warlords in Kandahar, about 70 miles southwest of here, complain that their commanders rarely pay them. They apparently were intent on seizing whatever they could from people living in what they regard as hostile territory. They allegedly stole cash, jewelry, watches, radios, three motorcycles -- even the mud-brick school’s windows and doors -- before leaving with U.S. and Afghan troops Saturday.

“These people are robbing us, torturing us and beating us,” said Sultan Mohammed, a village elder. “They are also taking innocent people to jail.”

Dai Chopan is a remote village of about 5,000 people spread across several square miles in the barren mountains of southeastern Afghanistan’s Zabol province. Taliban forces have launched repeated attacks in the area in recent months, killing aid workers and U.S. and Afghan soldiers.

Outside its dust-covered adobe farmhouses and small shops, burlap sacks bulging with freshly harvested almonds are piled like sandbag bunkers, waiting for shipment to market on the few trucks that venture this deep into Taliban territory.

Dai Chopan lies near the border between Zabol and Oruzgan provinces, both of which are Taliban strongholds and suspected hide-outs for the Taliban’s Al Qaeda allies. Zabol was the scene of fierce battles between the Taliban and U.S.-led forces in August, the bloodiest month since the Taliban regime was overthrown in December 2001.

A senior Taliban commander, Maulvi Faizullah, announced last month that he had sent 300 reinforcements into mountainous Dai Chopan district, which surrounds the village, to join 1,000 Taliban fighters already here.

But residents insist that the village itself isn’t a Taliban or Al Qaeda base, and said men wrongly arrested as Taliban suspects included a shopkeeper and the son of the government vaccination coordinator.

U.S. troops have conducted three search operations in the village over the past several months, said Mohammed, 50, the village elder. Each time, he said, they brought the militia fighters, who followed Americans’ orders during house-to-house searches and arrests and -- each time -- beat and robbed villagers.

“They stand with the Americans, and when Americans leave an area, then the militias go by another route and rob the houses,” Mohammed said.

The villagers said assaults and thefts are common when militia members from Kandahar join U.S. troops in raids on the region’s villages, as they have for months. The militia members are loyal to Kandahar warlords Haji Granai, Haji Habibullah Jan and Toar Jan, whose brutality during Afghanistan’s civil war in the early 1990s was among the factors that led Afghans to support the takeover by the hard-line Taliban.

Mohammed and other elders said the village had no quarrel with the new Afghan army’s Central Corps force, which is dominated by ethnic Tajiks and other northern Afghans. But they regard the militia fighters, who share the same Pushtun blood as the villagers, as vicious criminals.

Afghan militia members “are placed under the [U.S.-led] coalition’s tactical control from time to time” but are released to their normal militia commanders “upon completion of a predetermined action or time period,” said Col. Rodney Davis, the American military’s chief spokesman at Bagram air base, north of Kabul, the capital.

“The coalition enjoys a great relationship with the Afghan people,” Davis added Monday in a brief e-mail reply to a request for a detailed interview on the villagers’ allegations. “The coalition is reasonably sure -- virtually certain Afghan militia forces conduct themselves in a professional manner while operating under coalition control and we’ve had no reports to the contrary.”

U.S. soldiers who spoke with a reporter in Dai Chopan did not identify their unit, or themselves, but an American military officer later said they were regular Army forces.

Gen. Mohammed Moin Faqir, commander of the Afghan National Army’s Central Corps, confirmed that the Kandahari militia fighters work as guides for U.S. soldiers.

“They are given those [U.S. military] uniforms so that in case there is any problem, there should be no doubt whether they are friends or enemies,” Faqir said in Kabul. The interview was monitored by a U.S. Army National Guard colonel, who is an advisor to the Afghan army.

“They know the area very well because that’s their home,” the general said. “They don’t understand maps or anything. They just show the path. Nothing else.”

John Sifton, Afghanistan researcher for Human Rights Watch, said U.S. commanders would still be legally responsible if there was a pattern of abuse by the militias and the Americans did nothing to stop it.

“The question is: Should they have known about it?” Sifton said from New York. “If they were closing their eyes to it willfully, it’s just as if they knew. If they honestly, and earnestly, did not know, that is a defense.”

The U.S.-led operation was part of a sweep that began Oct. 8 in the village of Shahi Gaz, northeast of Dai Chopan, said 1st Sgt. Abdul Bari, one of the first Afghan soldiers to arrive that day on twin-rotor U.S. Chinook helicopters. At its peak, the operation included about 400 troops and militiamen, including up to 50 Americans, said Afghan army Maj. Taza Gul, operations officer for the Central Corps’ 1st Battalion.

Their mission was to find about 300 Taliban guerrillas, who two days earlier had killed eight fighters loyal to the local government in a 2 a.m. attack on Shahi Gaz, then escaped into the mountains, Bari said.

There was no combat during the 17-day search mission, but Bari said that Mullah Janan, a high-ranking Taliban commander, was captured outside Dai Chopan. Soldiers also seized three truckloads of rocket-propelled grenades, mortars, artillery shells, antiaircraft rounds and other ammunition in the village. The ordnance was destroyed Friday.

Afghan army troops agreed to allow a reporter to enter the village Friday after reviewing a letter of permission signed by Faqir. But a U.S. soldier intervened and, after making a radio call to his superiors, said Davis, the Bagram base public affairs officer, had ordered that no one be allowed in.

That evening, about 30 village elders sat in a circle in the home of Dai Chopan’s district commissioner and by the light of an oil lamp, told their stories of attacks and theft by the militiamen.

Haji Abdul Karim, 40, a delegate to the loya jirga, a traditional grand council that is to decide Afghanistan’s new constitution in December in Kabul, had several cuts above his left eye and raw welts crisscrossing his back. He said the militiamen inflicted the injuries before stealing $220 from him, a year’s income for many Afghans.

Mohammed and other villagers said the militia forces searched houses and, after arresting villagers accused of being Taliban members, demanded bribes of more than $1,000 to release each one. About 25 men were taken to Kandahar as prisoners, according to villagers.

They said the U.S. and Afghan National Army soldiers were welcome in Dai Chopan, but they blamed the U.S. troops for allowing the militiamen to abuse them.

“The Americans are responsible for this. They brought the Kandaharis here,” said Shamsullah, whose wife and two sons lay in excruciating pain on the floor of his mud-brick house. Like many Afghans, Shamsullah has only one name.

His 21-year-old son, Nasrullah, was in a cramped bedroom, softly grunting. His father said a sharp blow had fractured the back of the young man’s skull. His buttocks and back were covered in dark bruises.

“Nasrullah hasn’t spoken yet. He has been unconscious since he was beaten,” his father said. “He is not able to speak or move. He has been beaten on the back of his head with a Kalashnikov [assault rifle] butt.

“There was no blood on his head,” Shamsullah said. “It was just caved in when they found him.”

With the closest doctor a six-hour drive on a bumpy dirt track, the family is depending on the village health worker and pharmacy for medical help.

Two empty plastic intravenous bottles hung from a nail in the wall above Nasrullah’s head, which the medical worker had administered, along with a few injections, the family said.

The only other medicines they could get at the pharmacy were over-the-counter remedies, which spilled out of a small blue plastic bag next to the young man’s pillow. There were several brands of headache tablets, a tube of pain-relief gel, a bottle of vitamin syrup and antibiotics.

Even though Shamsullah feared his son might be slowly dying, he never considered taking him to U.S. troops for medical care.

“These Americans brought the militias here,” said Mohammed, the village elder. “If we take our injured people to them, I don’t think they will help us. We are also afraid of them.”

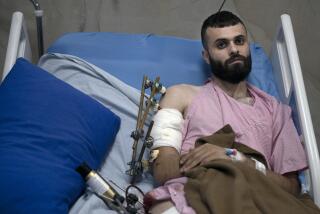

Abdul Rahim, 25, lay a few feet from his brother, his right arm in a knotted cloth sling. He winced as he rolled over to show his buttocks, hips and back, which were covered with large bruises, deep cuts and lash marks.

“There were three guys who were beating me,” he said. “One was standing behind me. The two others were standing on my feet. They were kicking me, and the one on my back was beating me with sticks.”

“I was still able to get up, and then I tried to go and see my brother. So they hit me with the butt of a Kalashnikov, and I was unconscious after that. I don’t know what happened then.”

Abdul Rahim said he was in his room when the militia fighters arrived at his family’s house and told him to hand over his guns. Like most Pushtun men in Afghanistan’s harsh frontier regions, he had hidden firearms, but tried to lie his way out.

“I told them that I don’t have guns, but they insisted,” Abdul Rahim said. “And I had a pistol and a Kalashnikov, so I gave them those. Then they said again, ‘You have more guns.’ I told them, ‘No, I don’t have more guns.’ They said: ‘You are feeding the Taliban. You are supporting them. Come with us. We will take you to the Americans.’

“I didn’t know that they were taking me somewhere else. We were walking toward the Americans, and then they turned me toward a hidden area,” he said.

Abdul Rahim said he and his brother ended up in two empty, roofless rooms, about 3 yards by 2 yards, normally used for storing almonds behind the family orchard. The U.S. soldiers’ camp was just a few hundred yards down the hill.

The militiamen tortured his brother in one room while he waited in the other, Abdul Rahim said. “I heard him shouting, ‘Don’t hit me, for God’s sake, don’t beat me -- if you have a God.’ ”

Their younger brother Bakh- tullah, 12, found the men unconscious in the storage rooms. Neighbor Hazrat Gul, 30, said he and two other men wrapped them in blankets and carried them home.

He said the Kandaharis also came to his house and stole his watch, a chicken and $55 in Pakistani rupees, a common currency in the border regions of eastern Afghanistan.

On Saturday, the two beaten men’s mother, Doolkhoor, lay alone, outside, on the dirt floor of a small, bare courtyard, hoping the warmth of a mountain dawn would help ease her pain.

To remove any doubt that Doolkhoor, 40, had been attacked, Shamsullah broke the strict Pushtun taboo against allowing another man to see his wife and lifted a blanket she had pulled up over her face.

Her right arm was bound tightly to her chest with a strip of cloth, and her face contorted in agony as she turned to the wall to preserve her honor. Militiamen broke her shoulder with a rifle butt, her husband said.

When they knocked her to the ground, she was carrying $370 in rupees and was ready to pay for her sons’ release. The bribe was too small, and the Kandahari militiamen took the money and continued torturing her sons, Shamsullah said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.