Hezbollah’s role in Syria fighting threatens to spread holy war

- Share via

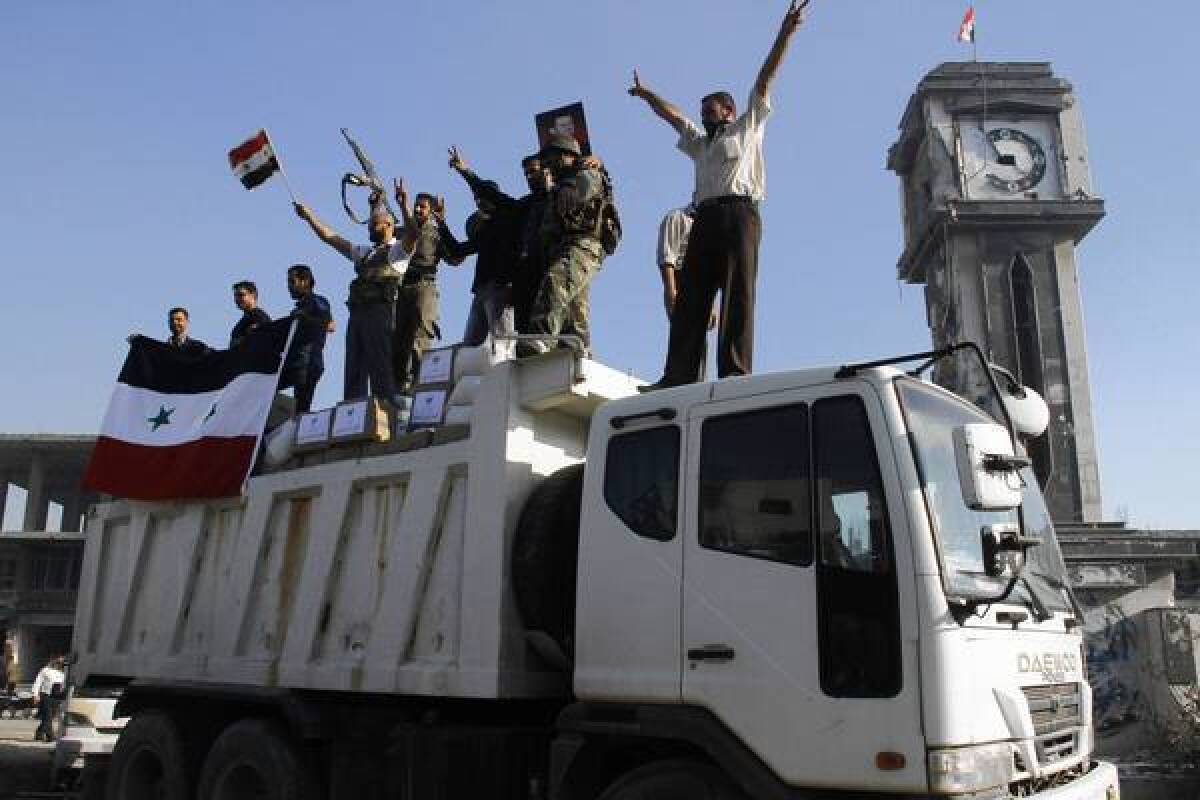

CAIRO — Hezbollah’s march into the Syrian civil war on behalf of President Bashar Assad is adding to tension along sectarian fault lines in a region increasingly roused by geopolitical maneuverings that are fueled by religious passions.

Popular uprisings that overthrew secular autocrats in Egypt and other countries once enthralled Shiite and Sunni Muslims alike. But the replacement of fallen leaders by Islamist parties has further provoked the age-old vitriol between the sects, threatening to turn the Syrian battleground into a wider religious war.

Hezbollah, long a proxy for Shiite-dominated Iran, is helping battle largely Sunni rebel forces seeking to overthrow Assad, a fellow ally of Iran whose Alawite faith is a spinoff of Shiite Islam. The accelerating role in Syria of the Lebanese-based Shiite militant group has infuriated Sunni-led Arab states of the Persian Gulf, including Saudi Arabia, which for decades have jockeyed against Iran for regional dominance.

Sectarian warfare is one of the most potent dangers arising from the so-called Arab Spring. Changes in the established order upset Iran’s regional designs, highlighting the Shiite-Sunni bitterness that has also threatened Iraq since long before U.S. troops withdrew in 2011. A growing concern is that religious enmity may ignite fresh bloodshed in Syria that would radiate across the region.

“Arab states see Syria as a place to exhaust Iran’s capabilities and keep it distracted from other issues it might be concerned with in the Arab world,” said Rabha Alam, a researcher at Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo. “Hezbollah entering the equation has quickened the pace of sectarian rhetoric and turned it into a Sunni-Shiite conflict.”

Hezbollah embodies the fear that Sunni-led nations have of Iran, the preeminent Shiite voice, using the Syrian war to foment wider instability. Syria has become a struggle not just between Assad and the rebels, but for opposing Shiite and Sunni radical networks whose fighters come from as far away as Cairo and Tehran.

“Hezbollah is part of the Iranian conspiracy which has a strategic objective in the region,” said Mustafa Alani, a senior analyst at the Gulf Research Center in Geneva. “It has really changed the rules of the game.”

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah argues a counter-narrative: Before his men arrived in Syria, gulf state-funded Sunni militants, some with ties to Al Qaeda, infiltrated and are now commanding rebel factions. This scenario, he says, endangers Hezbollah’s benefactor, Assad, and also threatens neighboring Lebanon with a volatile brand of Sunni extremism.

Directing his comments to Sunni radicals, Nasrallah said in a recent speech that Arab states were instigating religious hatred and that anyone “who thinks that he can force us to change our stance through killing and terrifying is mistaken.”

The specter of Hezbollah militants set loose in Syria, where they recently were victorious in the pivotal battle for Qusair, has sent tremors through Egypt and other Sunni-dominated nations. Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood’s party broke diplomatic relations with Damascus and have tacitly endorsed calls by clerics for Egyptian men to travel to Syria and fight.

“Every Muslim population must protect their brothers in Syria,” said Sheik Yusuf Qaradawi, a popular Egyptian-born cleric who lives in Qatar and appears frequently on TV. “The nation is ready for sacrifice and jihad and we must call for jihad to defend religion and God’s law.”

The comment was classic Qaradawi but it echoed across an Egyptian landscape easily aroused by religious rhetoric. Cairo’s new Islamist-controlled government is under pressure from ultraconservative Sunni preachers to keep wide the divide between Sunnis and Shiites. Morsi’s overtures this year to restore diplomatic ties with Iran after decades of estrangement were vilified by many clerics.

Similar anti-Iranian sentiment is pervasive in the gulf, where Bahrain accuses Tehran of inciting the kingdom’s Shiite majority to protest against the ruling family. Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, which also has a restive Shiite minority, have repeatedly accused Iran of sectarian intrigue while warning that Tehran’s nuclear program may spur a regional arms race.

“A Saudi cleric was on TV thanking Nasrallah for getting the Sunnis to finally unite. Without Hezbollah going into Qusair none of this would have happened,” said Riad Kahwaji, founder of the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. “For the gulf states, the fight in Syria is with Iran.”

Saudi Arabia and Qatar have funded and armed the rebels seeking to bring down Assad. The equation may change in coming months, especially after the U.S. decision to arm rebel groups. Washington will not aid Islamist extremist fighters and may pressure gulf states to stop backing radical factions.

“What gulf states wanted was for the U.S. to organize and lead from behind,” said Kahwaji. “They’re asking the U.S. to make a plan and lead on the operation’s table and provide intelligence support such as drones, satellites, etc. Sort of Libya style.”

Other political shifts could also alter the dynamics. It’s too early to tell whether Iran’s newly elected president, Hassan Rowhani, a moderate, will ease tension with neighbors. Despite his conciliatory language for diplomacy, the ultimate power in Iran is supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has pursued hard-line policies on regional matters and with the West.

Political manipulations of Shiite-Sunni enmity, which dates back centuries to a struggle over a successor to the prophet Muhammad, may also be at work. Arab states, according to some analysts, may find it tempting to play on religious suspicion to deflect public attention from economic and social problems.

Saudi Arabia is contending with a huge population of disillusioned, unemployed young people. Egypt’s economy is faltering and political unrest is deepening ahead of demonstrations planned for Morsi’s one-year anniversary as president on June 30. Across the Arab world, the broken promises of the uprisings have triggered despair and rising anger.

Hezbollah’s entry into the Syrian civil war “has led preachers and leaders in gulf states to adopt the discourse of ‘victory for [Sunnis],’” said researcher Alam. “This keeps populations distracted from internal issues. This provides an important service to the gulf.”

“This is happening in Egypt now,” she said, as leaders and clerics try to siphon attention away from the government’s failings. But there are consequences of rallying the region’s young men around the fractious Syrian war and its dangerous religious implications.

“If we are sending our children to Syria, then which banner will they fight under ... what will they be armed with?” Alam said. “Or will we just be sending them off to die.”

Special correspondents Alexandra Sandels in Beirut and Ingy Hassieb in Cairo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.