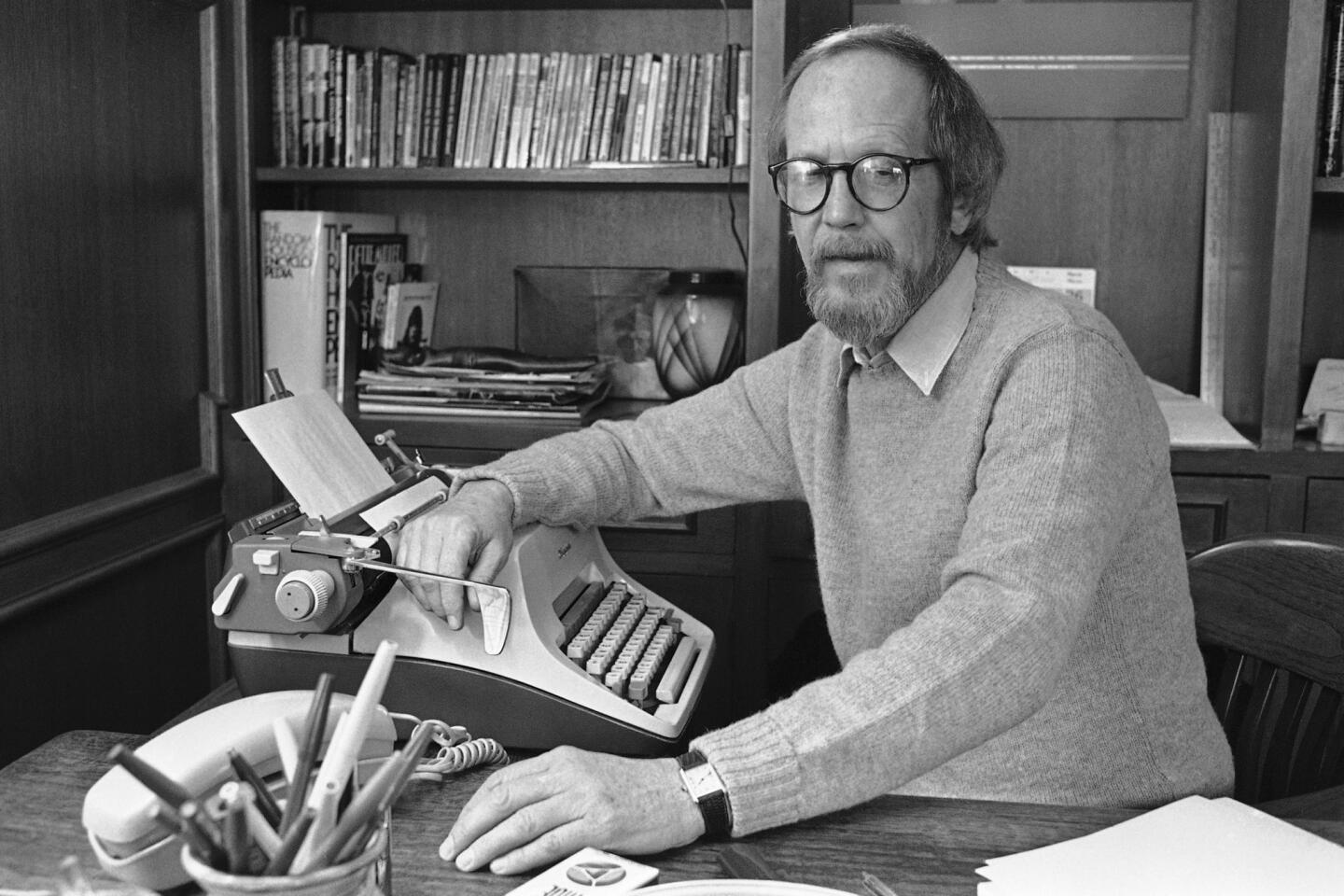

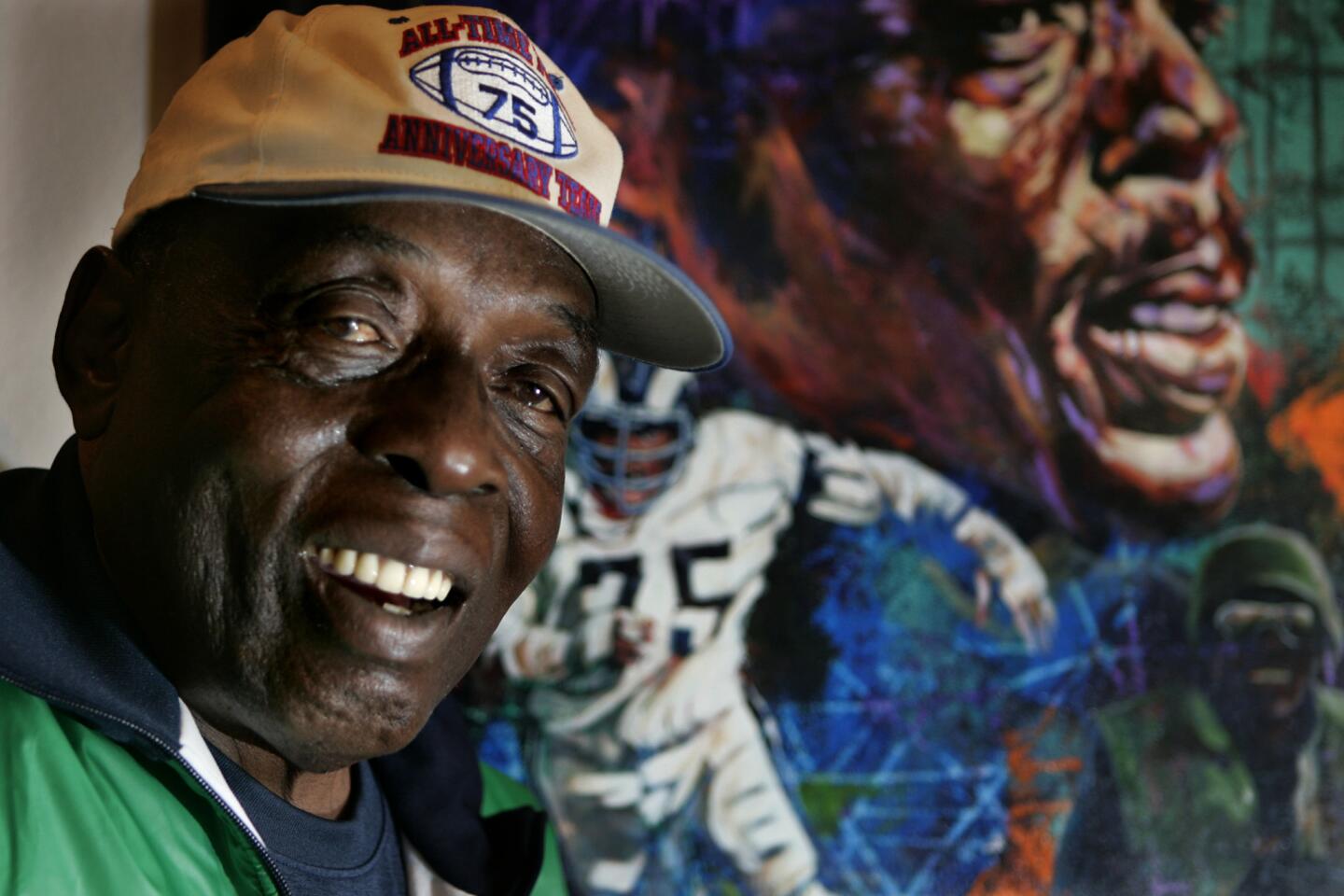

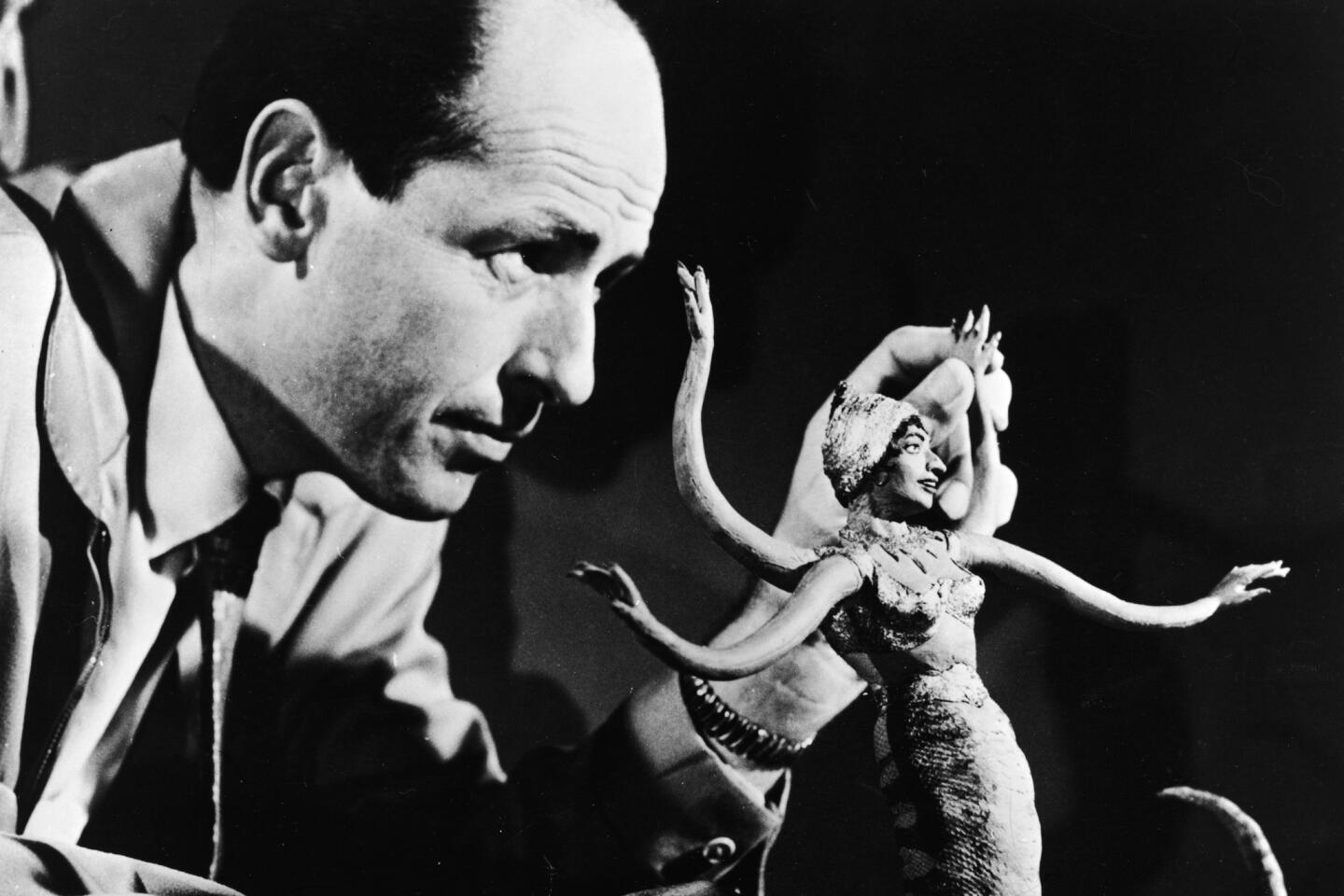

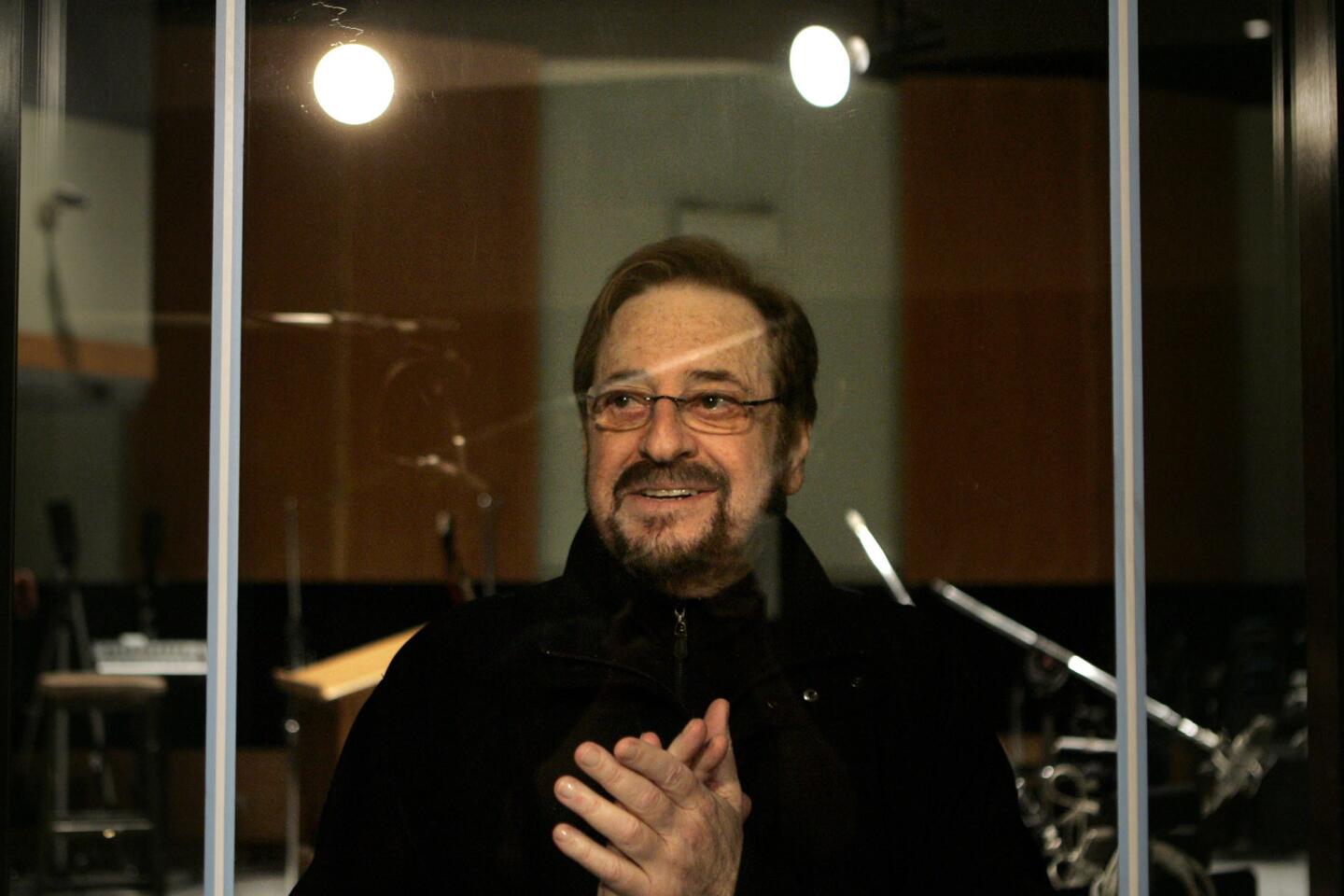

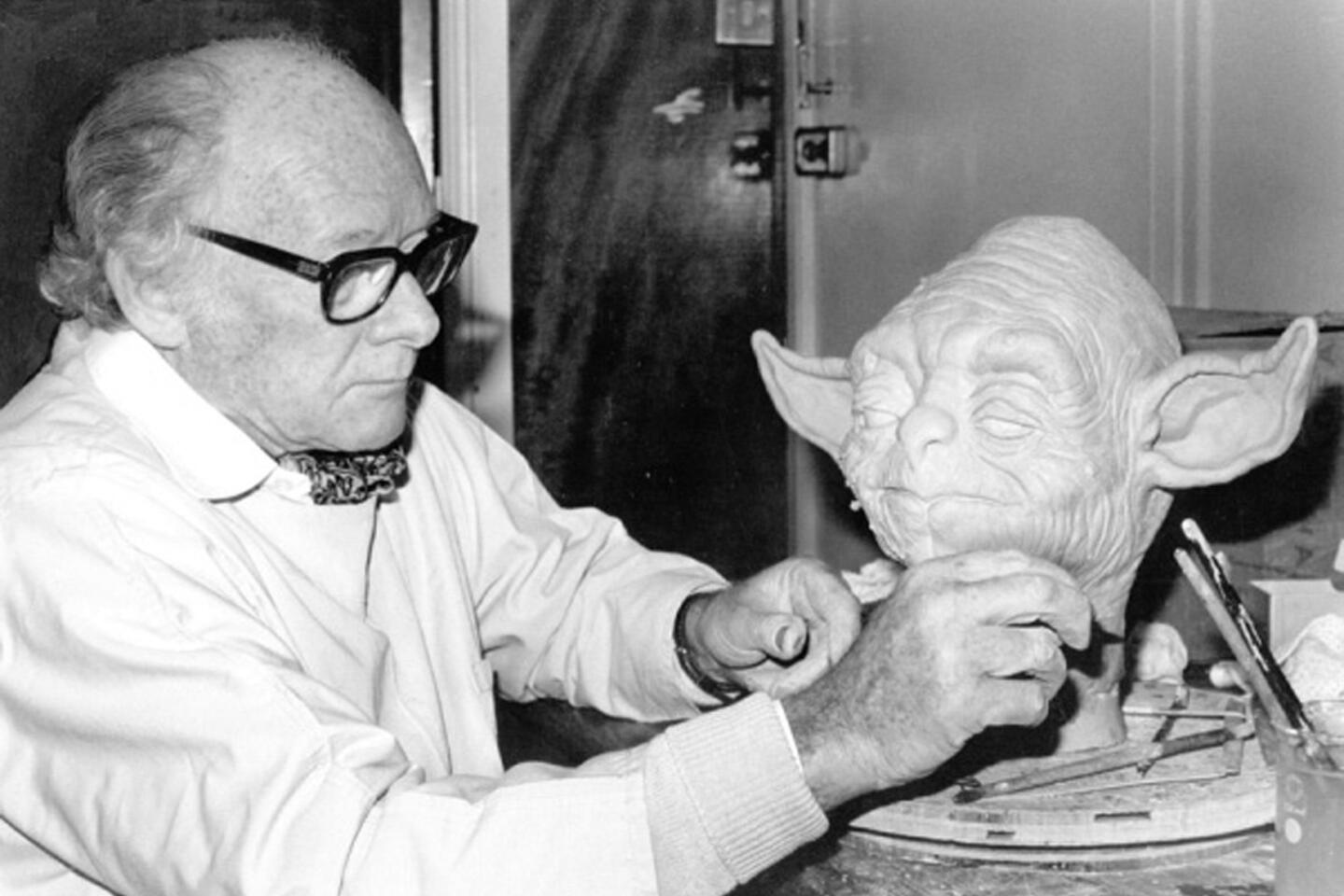

Micky Moore dies at 98; director and early Hollywood actor

- Share via

Micky Moore and Hollywood grew up together.

He was a toddler in 1916 when he began his career as a child actor in silent films and sat on the laps of such leading ladies as Mary Pickford and Gloria Swanson. As a 5-year-old he worked with legendary director Cecil B. DeMille, who would mentor Moore as he transitioned to directing in adulthood.

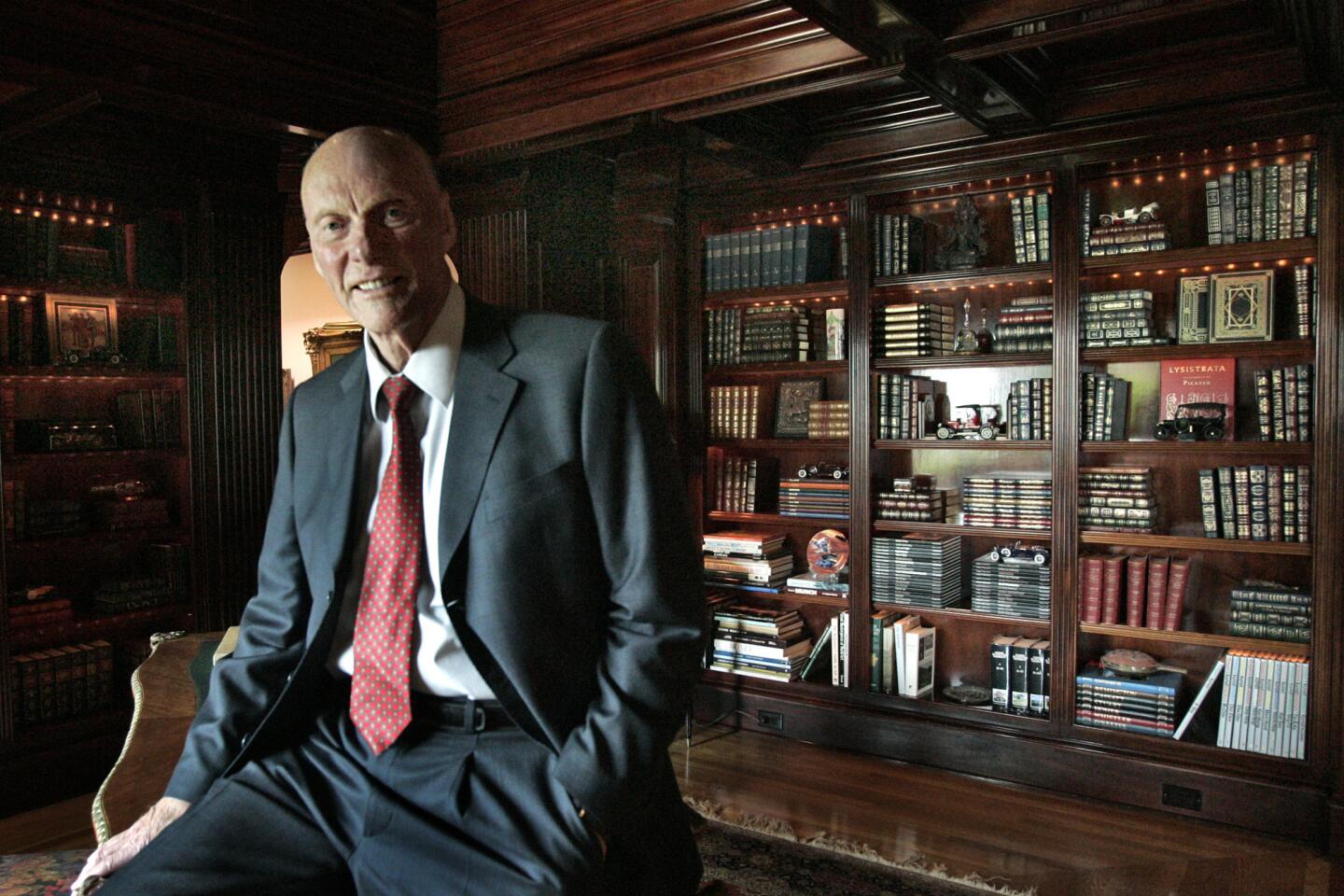

As the motion picture industry moved from silent pictures to sound and into the digital era, Moore would contribute to more than 200 movies over nine decades. He experienced so much Hollywood history firsthand that he was moved to preserve it in a memoir published when he was 95. He called it “My Magic Carpet of Films.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

When Moore finally retired from the business, in his late 80s, he was regarded as a leading second-unit director for his work on such films as “Patton,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and the first three “Indiana Jones” movies.

Moore died March 4 at his longtime home in Malibu of congestive heart failure, his family announced. He was 98.

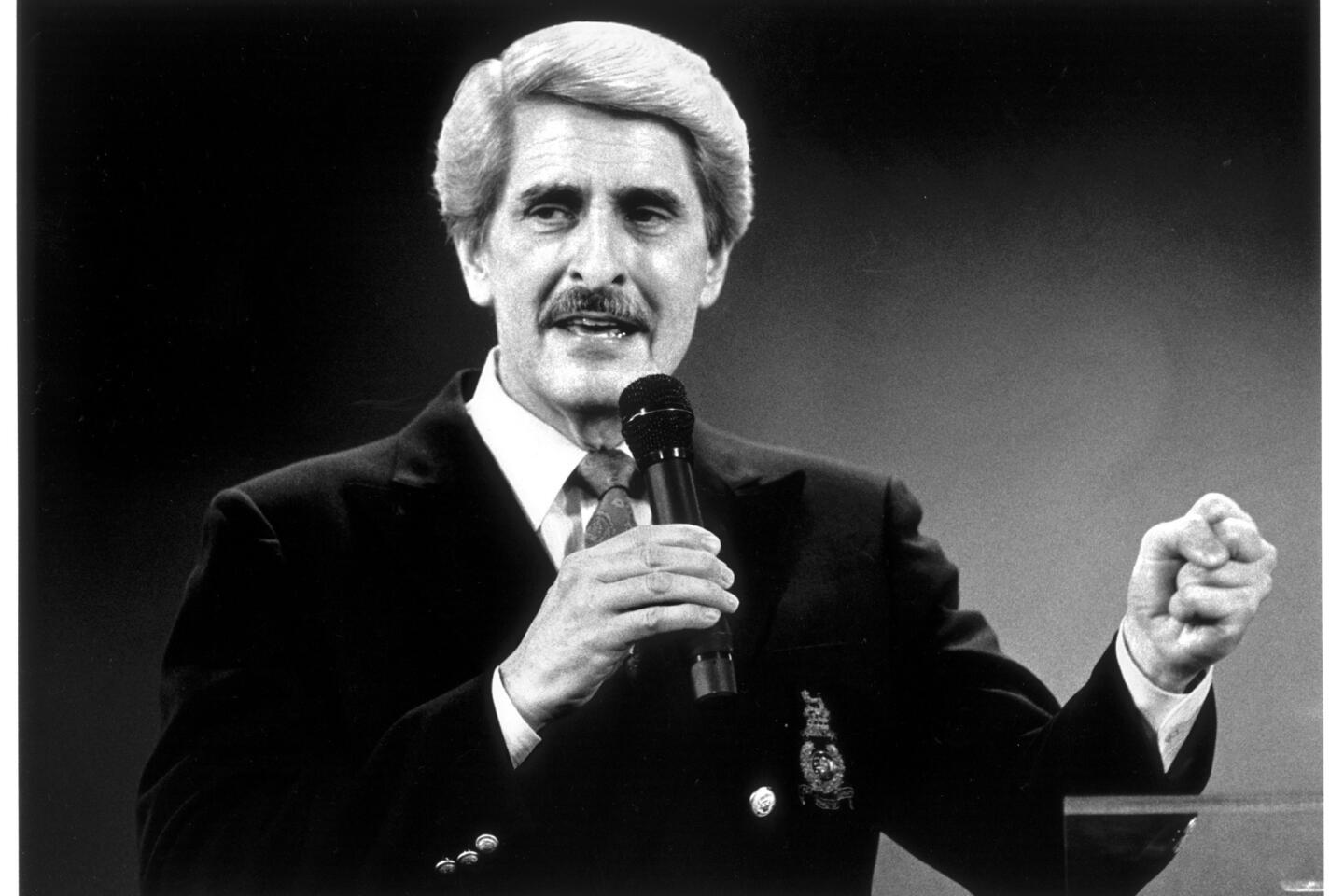

“He was amazing because the pictures he was second-unit director on, such as ‘Patton’ and ‘Indiana Jones’ have the highest reputation for their action. And who did the action scenes?” film historian Kevin Brownlow asked rhetorically in an interview with The Times.

The answer is, of course, Moore.

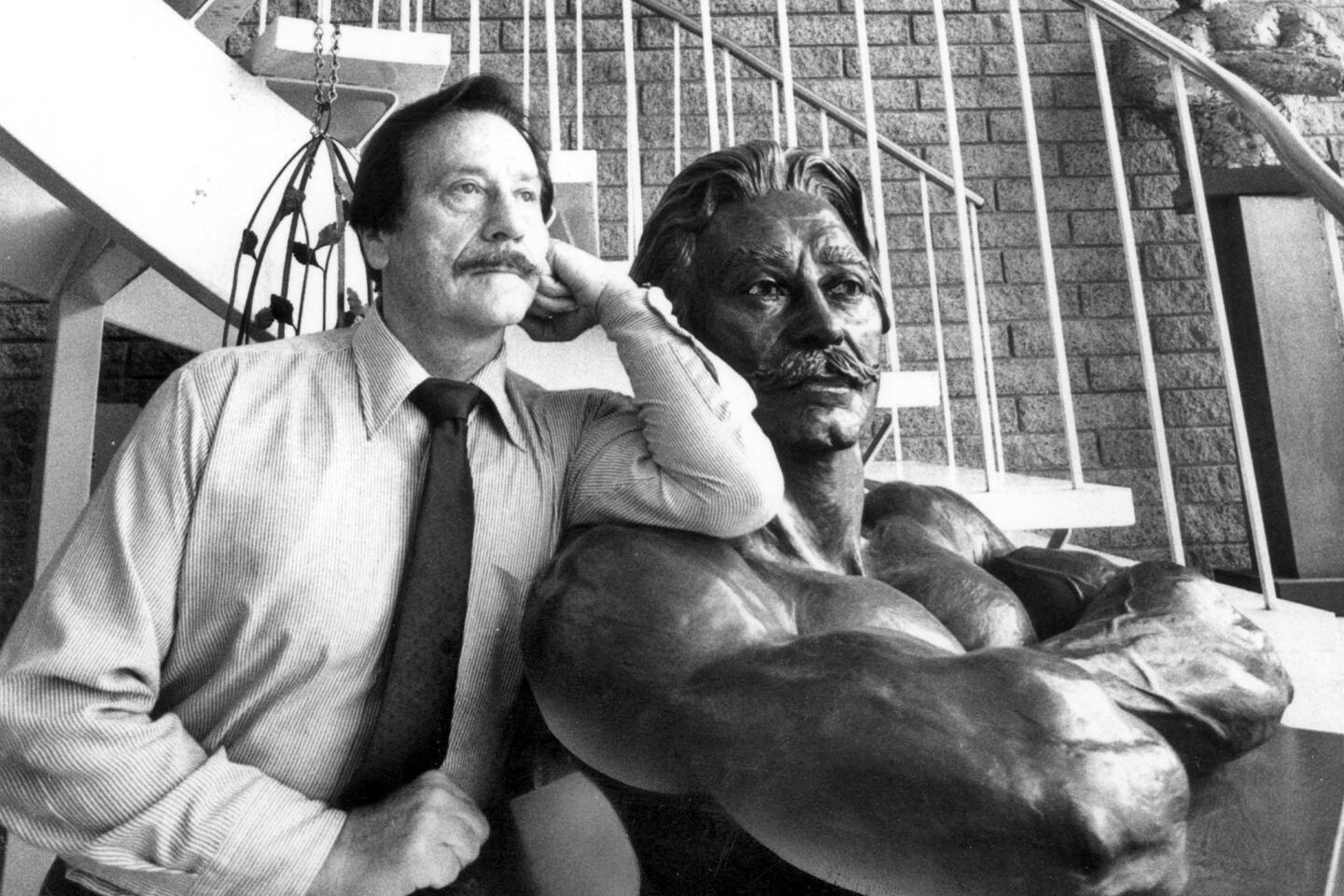

Over three decades he made nearly 40 films as a second-unit director shooting action and background footage while the primary director was engaged elsewhere. Hewing to another director’s vision didn’t bother Moore, known for bringing kindness and gentleness to his Hollywood sets. Besides, he said, the top directors had the confidence to take his advice.

“If you are good, you shouldn’t even be aware that a second-unit director has been involved,” Moore said in 2009 in the Malibu Times. “I just did the best I could possibly do on each shot, so they kept asking me to make more movies.”

When filmmakers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg needed a second-unit director for “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981), Moore was their first choice, and a perfect one, Lucas later recalled.

“Micky Moore was exceptional.... He was confident behind the camera and knew when to speak up to make things better,” Lucas wrote in a foreword to Moore’s 2009 book.

After Moore suggested that the truck-chase scene he would direct in “Raiders” could be improved by moving it from an empty desert to narrow tree-lined streets to give it context, the change was made. The results, Lucas wrote of the now-iconic scene, “speak for themselves.”

Spielberg wrote in another foreword to Moore’s book: “He saw around the corners of my imagination and made significant contributions. For this and for his friendship, I shall always be grateful.”

He was born Dennis Michael Sheffield in October 1914 in Vancouver, Canada, one of four children of Thomas Sheffield, a shipbuilder from Britain, and Norah Moore, an actress from Dublin.

After his family arrived in Santa Barbara by boat in 1915, they lived near a branch of the American Film Manufacturing Co., known as the Flying “A” Studio. When a neighbor suggested that brother Patrick, then almost 4, audition there, 18-month-old Micky — with his mop of curls and expressive eyes — was soon employed as well.

To further their careers, the family moved to Los Angeles in 1916, and Micky Moore was making $200 a week in 1920. His mother wanted the boys to use her last name professionally.

Patrick appeared in dozens of silent pictures, including the 1923 version of “The Ten Commandments,” and later worked at Paramount Studios in music and sound editing. He died at 91 in 2004.

Their father maintained a lifelong affinity for the water. He was a founder of the original Santa Monica Lifeguard Service in 1916 and helped pioneer the American Red Cross safety program on the West Coast.

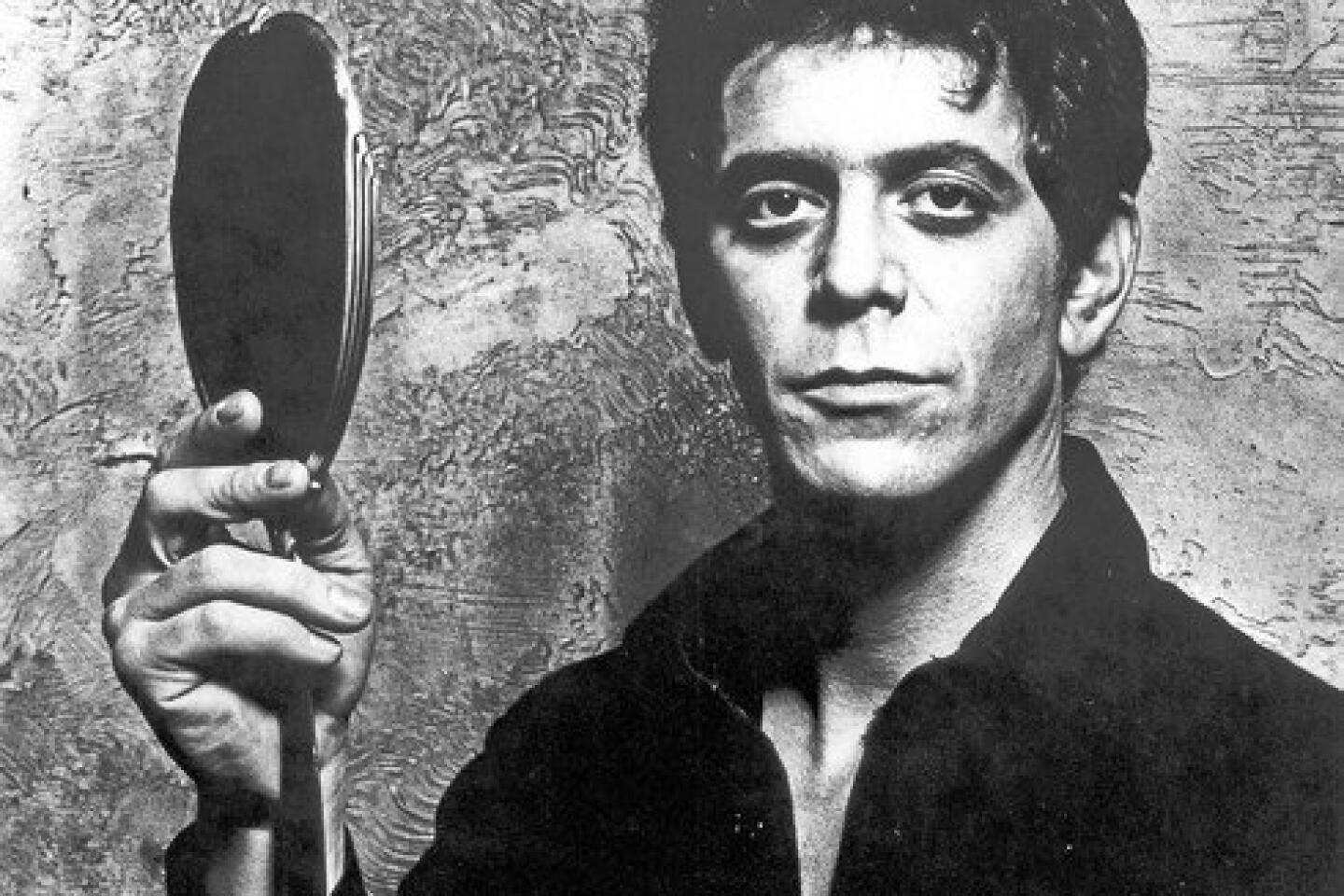

Young Micky soon joined the new Lasky studio, known as the Famous Players-Lasky Corp., where he spent much of his childhood. He often played the son in the dozens of silent films he made until the late 1920s.

The first film he made in the emerging Hollywood was “The Poor Little Rich Girl” (1917) with Pickford.

According to Brownlow, some of Moore’s more significant films as an actor include 1921’s “All Souls’ Eve” with Mary Miles Minter; “Abraham Lincoln,” a 1924 production lost to history; 1926’s “No Man’s Gold” with Tom Mix; and “The Lost Romance,” a 1921 movie directed by William DeMille, Cecil’s brother.

While making “For Better, for Worse,” a 1919 movie starring Swanson, Moore came to know director Cecil B. DeMille, who “helped to shape my character and made me the person I am today,” Moore wrote in his book.

At 12, Moore was cast in one of his final lead acting roles, as the young apostle Mark in the 1927 biblical epic, “The King of Kings,” directed by DeMille.

The difficulty of moving from child actor to more mature roles was compounded by the Great Depression, which hit his family hard just as silent movies were going out of vogue. At 15, he appeared in his final film.

He worked on fishing boats off Santa Monica but didn’t like it much, and in 1933 he married Esther McNeil, his sweetheart from Venice High School.

Missing the movie business and needing to support his family, he made an appointment to see the man he always called “Mr. DeMille” and surprised him by asking to work in the property department. Late in life, Moore pointed to DeMille’s saying “yes” as the happiest day of his life because it set up the rest of his career.

In the late 1940s, Moore segued to the role of assistant director at Paramount Studios and also worked with DeMille in that capacity, including on his final film, “Ten Commandments” (1956).

As an assistant director, Moore contributed to “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (1957), the James Bond film “Never Say Never Again” (1983) and seven Elvis Presley movies. He helmed one Presley movie as director, “Paradise, Hawaiian Style” (1966).

After wrapping up “102 Dalmatians” in 2000, Moore retired.

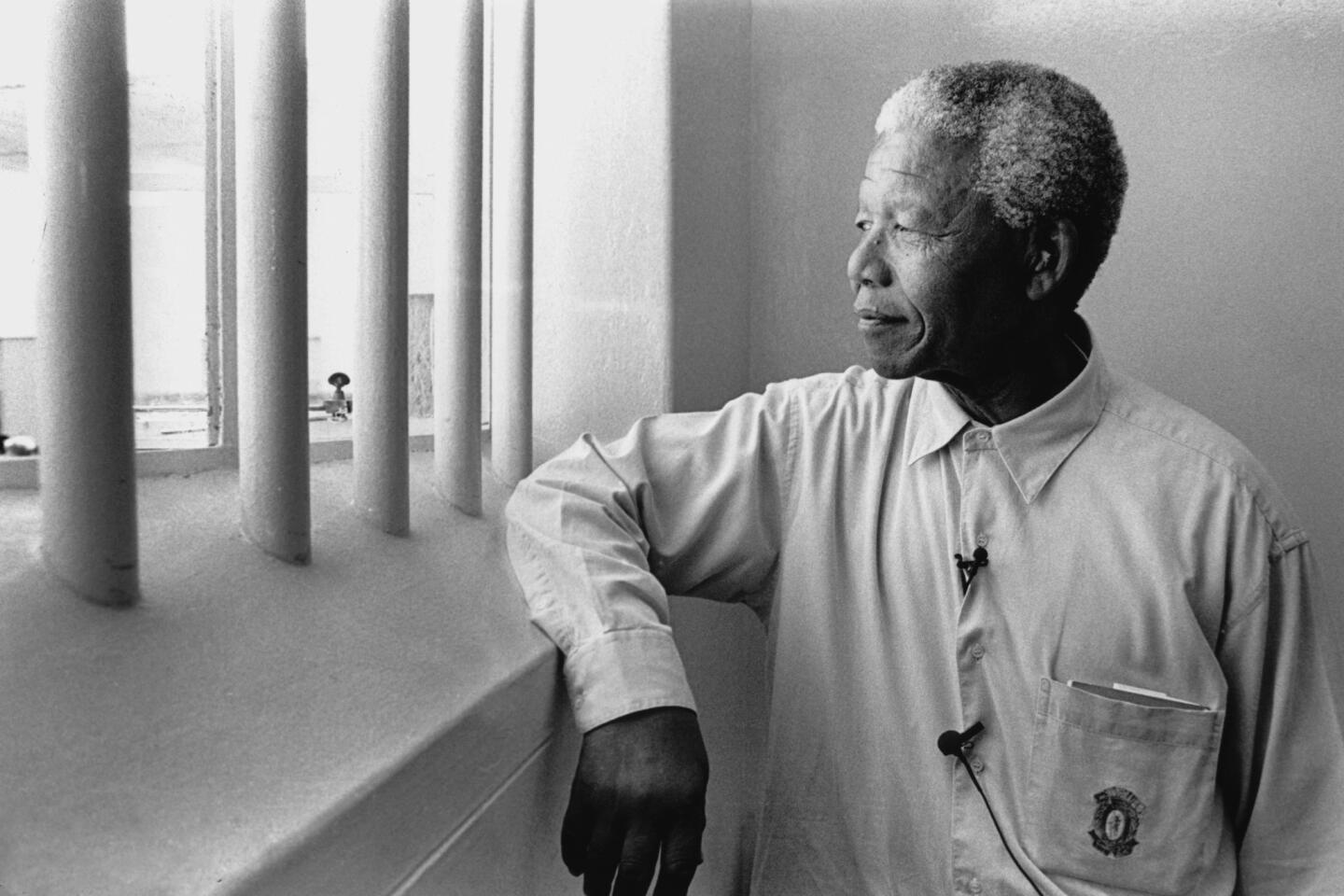

Since 1955, he had lived in an unassuming house on the beach in Malibu. His daily routine included swimming 40 laps at Pepperdine University’s Olympic-size pool, a regimen he maintained until he was 95 1/2.

His first wife, Esther, died in 1992. Five years later he married Laurie Abdo, who had been Howard W. Koch Sr.’s personal assistant at Paramount. She died in 2011.

Moore is survived by his daughters, Tricia Newman of Malibu and Sandra Kastendiek-Drake of Los Angeles; five grandsons; and four great-grandchildren.

Services will be private.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.