Iraqi shoe-thrower’s case is adjourned

- Share via

Reporting from Baghdad — It was the hottest ticket in town. It drew spectators from as far away as Sweden and sparked a scramble for choice seats. Police formed human chains to block the crowds that surged forward to glimpse the star attraction: a defiant-looking man in black loafers.

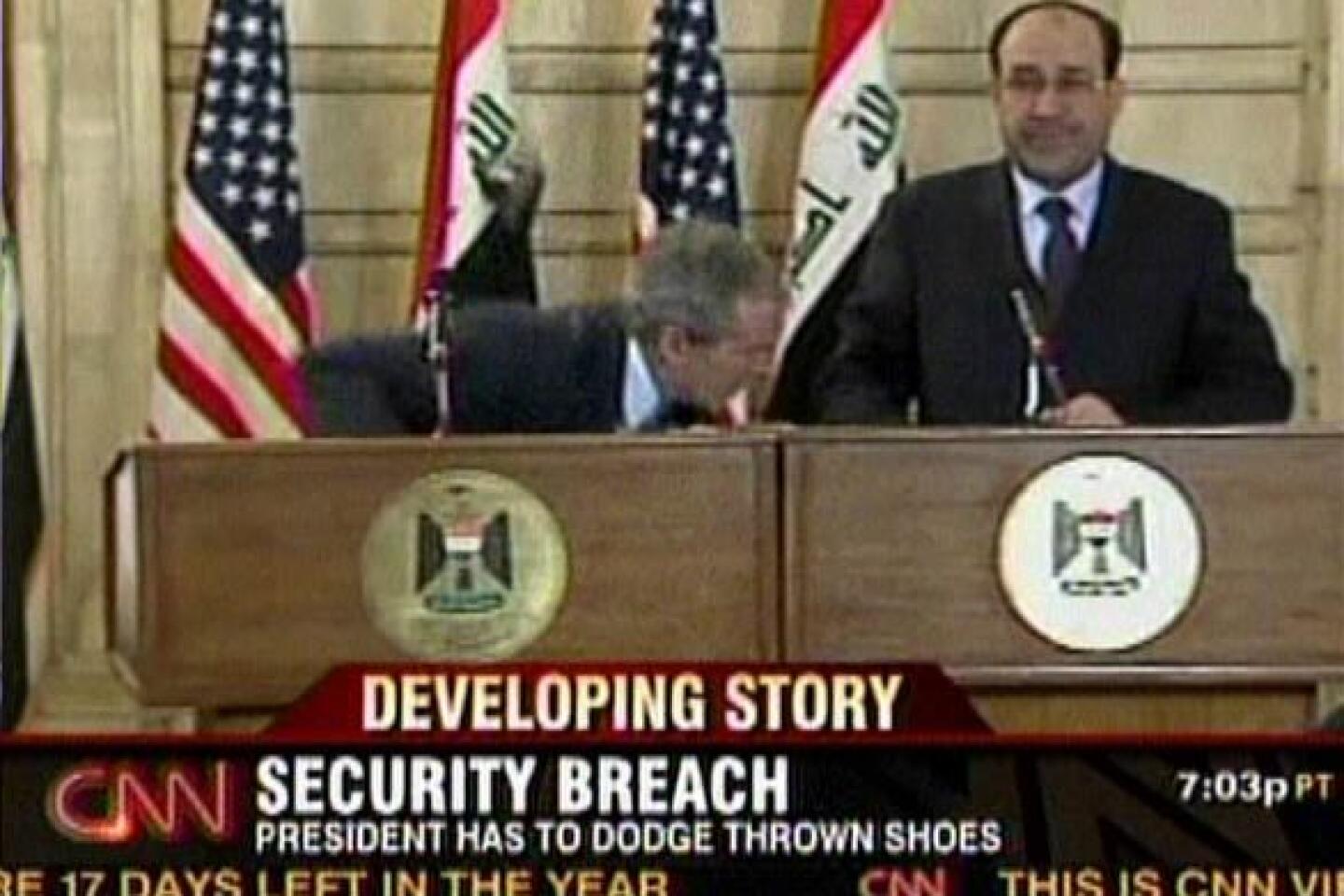

This time, Muntather Zaidi’s shoes stayed put as he went on trial Thursday for flinging his footwear at President Bush during a December news conference in Baghdad. If convicted of assaulting a visiting head of state, the Iraqi journalist could face 15 years in prison.

Nobody questions whether Zaidi, 30, hurled his shoes at the president’s face during Bush’s farewell visit to Iraq on Dec. 14. The act was captured live on TV and has been replayed endlessly, like a spectacular touchdown pass.

Nor does Zaidi deny trying to clock Bush as he stood at a lectern beside Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Maliki that night, shortly before the two leaders sat down to dinner.

On Thursday, standing in the wooden defendant’s pen, Zaidi said he acted in a burst of rage as Bush, “smiling that icy smile,” spoke of achievements in Iraq since the U.S.-led invasion of the country in March 2003 and mentioned his upcoming meal with Maliki.

Zaidi, voice calm but forceful and an Iraqi flag draped like a cravat around his neck, said it was more than he could bear.

“I thought about what the achievements were -- killing about a million Iraqis,” Zaidi said.

Everything but his target faded to black, he said, as he yanked off his shoes and threw them, one after the other. “I didn’t see anything but Bush.”

Zaidi’s legal team, more than 20 lawyers who jostled for space around the pen, cited two principal reasons why their client should not have been charged.

Bush was a drop-in guest, they said, not an official visitor to Iraq, hence Zaidi should not face charges of assaulting a visiting dignitary. Second, because the incident occurred in the U.S.-controlled Green Zone, they said, technically Bush was not visiting Iraq at the time.

Beneath those legal quibbles lies what Zaidi’s supporters consider the main issue: freedom to publicly oppose the U.S. presence in Iraq. They argue that throwing one’s shoes and calling someone a dog, as Zaidi did -- both supreme insults in the Middle East -- were his way of protesting the war and the presence of about 140,000 U.S. troops.

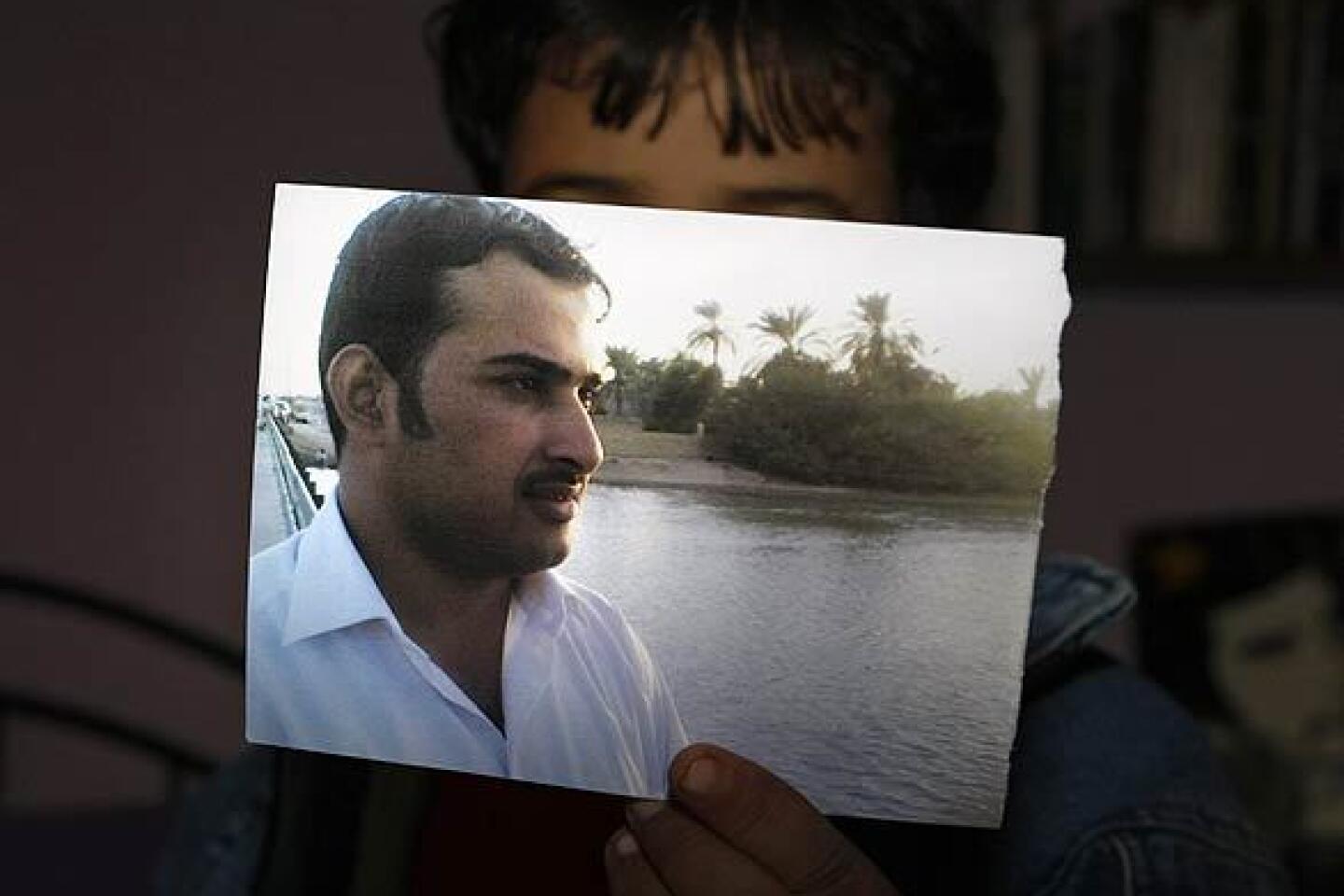

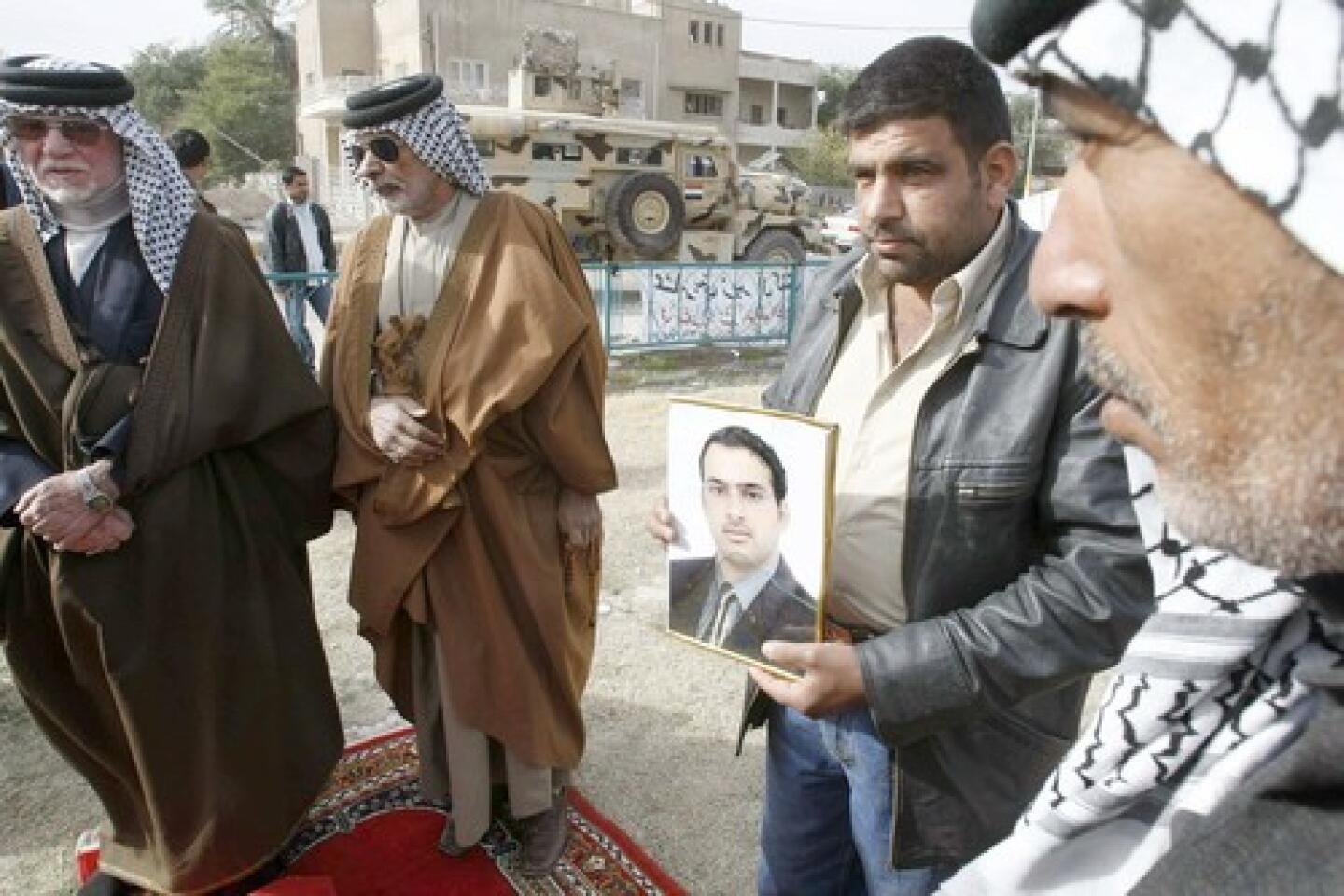

“My professors tell me this trial is unfair,” said one of Zaidi’s brothers, Maitham, a law student in Baghdad. He was holding court at a cafe beneath a giant shade tree outside the courthouse before the session began early Thursday.

Maitham was there with three of Zaidi’s five sisters, as well as aunts, uncles, young nieces and nephews and two other brothers. He said he would not feel different if the fast-flying shoes had hit their target and drawn blood. Neither touched Bush.

“It’s the principle,” he said. “It was just to insult George Bush. It’s freedom of expression.”

Asked whether it would be all right for someone to hurl shoes at Iraqi Prime Minister Maliki if he visited the United States, Maitham replied, “Yes, if Maliki occupied you!”

As he spoke, the Zaidi clan sat around tables drinking tea and eating a breakfast of meat tucked into soft, white bread. The men wore loafers, most in the style favored by Iraqi males -- leather, with square toes bending upward like banana boats.

Attorney Yayha Attabi, a loafer wearer himself, scoffed at the idea that leather shoes such as the ones his client threw could hurt anyone. “It was a light shoe,” Attabi said of the offending footwear, which lawyers say was destroyed by security forces for fear they might be rigged to blow up.

“There were no nails protruding. It was soft leather. Even if it were thrown strongly, it would not have hurt him,” Attabi said, speaking outside court at the close of the session.

The hearing began promptly at 10 a.m. in a vast courtroom with white stone floors, wooden benches and heavy green drapes. All 200 seats were filled, and extra chairs were brought in to accommodate spectators, who for the most part were seated on a first-come, first-served basis. The two front rows were reserved for relatives and close friends, including Jumana Kurawi, an Iraqi woman living in Sweden who said she knew Zaidi from many years ago.

She recalled Zaidi phoning her in Sweden on Dec. 14 to say he would be covering the Bush-Maliki news conference for his employer, the Cairo-based satellite network Baghdadiya TV. Kurawi tuned in to see “what kind of question he would ask.”

Two days later, after learning that Zaidi would face criminal charges, Kurawi flew to Iraq to support him and his family.

As the defendant entered the courtroom, applause erupted and most spectators stood up, either to get a better look or to express support. Zaidi glanced at the crowd but remained poker-faced.

The judge ordered quiet as Zaidi entered the pen. One of Zaidi’s young nephews waved at him. A little girl, one of Zaidi’s nieces, squirmed and began to fuss. No loafers for her -- she wore miniature faux gold lamé cowboy boots with rhinestones. The prosecutor’s cellphone rang.

After things settled down, two witnesses briefly gave accounts of the incident and suggested that Zaidi’s claims of having been beaten savagely by those who grabbed him after he threw his shoes were exaggerated.

When his turn came, Zaidi testified that he had been subjected to electric shocks and brutal beatings while in jail.

He also acknowledged that he had practiced throwing his shoes in hopes of one day having the chance to hurl some at Bush.

But he denied that he went into the Dec. 14 news conference planning to do it.

Instead, Zaidi said his emotions took over. “I was feeling that the blood of Iraqis was flowing beneath my feet, and he [Bush] was smiling,” Zaidi said as a man in the front row wept.

With a legal dream team objecting to the case on technicalities, court was adjourned after 90 minutes until March 12, when a three-judge panel will decide whether the charge is warranted.

Pandemonium erupted. Friends and relatives rushed to the pen, hoping to touch or kiss Zaidi. Guards yelled at the crowd to behave and leave the room.

In the corridor, police linked arms to prevent hundreds of onlookers from closing in on Zaidi. He waved at the mostly cheering crowd and raised his fist in the air before disappearing down the staircase, surrounded by guards.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.