Joseph Sax dies at 78; law professor wrote influential article on public trust doctrine

- Share via

In 1970, Joseph Sax wrote a law review article that laid the foundation for a court case that would become famous in the annals of California water.

More than a decade after publication of Sax’s seminal essay on the public trust doctrine, the California Supreme Court ruled that the state had a duty to take into account the public trust in allocating water resources — an opinion that ultimately forced Los Angeles to reduce diversions from the Mono Lake basin in the Eastern Sierra.

While arguably the piece that Sax is best known for, the Michigan Law Review article was just one of many influential works he wrote over the course of a long career as a legal scholar and law professor.

“I think Joe, more than anybody else, is responsible for the very existence of the field called ‘environmental law,’” said Barton “Buzz” Thompson Jr., a Stanford law school professor who with Sax wrote a leading textbook on water law. “Joe came up with some of the central concepts that are still key to environmental law.”

Sax died Sunday at his San Francisco home of complications from a series of strokes he had suffered since October, said his daughter Katherine Dennett. He was 78.

Sax had a reputation as an innovative thinker who pushed the law in new directions. “His whole theme was the community’s interest in natural resources as opposed to private interest in natural resources,” said Harrison “Hap” Dunning, professor emeritus of law at UC Davis.

The concept of public trust was not new, but Sax applied it more broadly to a range of natural resources, arguing that in the public interest, they deserved protection.

He was a driving force behind a provision of environmental law that has long been a thorn in industry’s side: citizens’ ability to sue to enforce environmental regulations.

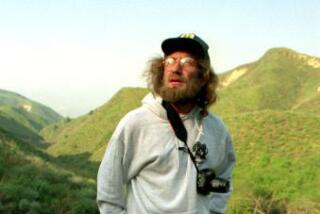

He hiked in the mountains and took his family on jaunts to national parks. “He was a solid environmentalist,” Thompson said. “He took the world seriously. To him it was not simply an academic exercise.”

Sax’s wife, Eleanor Gettes Sax, died in December. He is survived by his three daughters, Katherine Dennett and Valerie Sax, both of San Diego, and Amber Rosen of Los Altos, and four granddaughters.

Joseph Lawrence Sax was born Feb. 3, 1936, in Chicago and grew up in the city. He earned his undergraduate degree from Harvard University and his law degree from the University of Chicago. He taught at the University of Colorado and the University of Michigan before joining the UC Berkeley law school faculty in 1986. There he was the James H. House and Hiram H. Hurd professor emeritus of environmental regulation.

From 1994 to 1996, Sax served as counselor to Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt under President Clinton.

In a 2001 interview with the Portland Oregonian newspaper, Sax said that when he began teaching law at the University of Colorado, he was amazed that courses dealt with millions of acres of public lands but “were all about commodity development and private rights.”

So Sax designed a new course on conservation and the law. “Some people said, ‘It’s a fad. It shouldn’t be in the curriculum. You ought to teach something serious,’ ‘’ he recalled.

Among his books are “Mountains Without Handrails,” which dealt with the purposes and functions of the national park system, and “Playing Darts with a Rembrandt: Public and Private Rights in Cultural Treasures.”

Holly Doremus, who now holds the House and Hiram chair, met Sax when she was a law student and took one of his courses.

“I was just in awe of him,” said Doremus, adding that Sax, who wore bow ties, “had a kind of formal way about him that isn’t typical in the West.”

Later, when she started teaching at UC Davis, Doremus sent Sax an academic paper she had written. He invited her to address one of his classes.

“He was very welcoming to junior scholars. He was respectful, graceful in his scholarship,” Doremus said. “He could make really vigorous arguments. But there were never personal attacks on anybody.”

In recent weeks Doremus was collecting signatures from other academics to support Sax’s nomination for a lifetime achievement award from the environmental section of the California bar.

“Everybody wanted to be a part of this letter,” she said. “There are generations of environmental lawyers that have been inspired and educated by him and that wouldn’t be in their careers without him.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.