Op-Ed: GMO food labels are meaningless

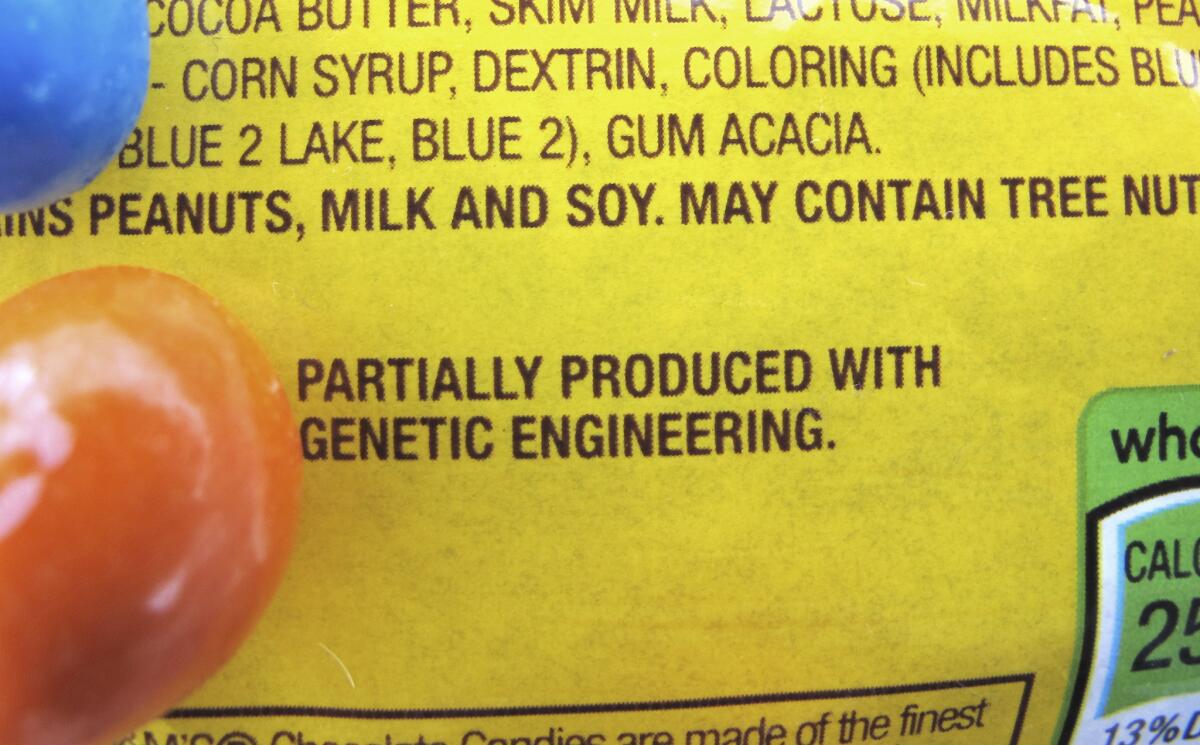

A new disclosure statement on a package of Peanut M&M’s candy in Montpelier, Vt. identifies them as being “partially produced with genetic engineering.”

- Share via

The push for labels on “genetically modi-fied” or engineered food is one of those social movements that sounds unimpeachable — like “Free the Whales” or “Save the Planet.”

What could be wrong with empowering consumers with knowledge about their food?

Plenty.

Many of the nation’s largest food companies, including Mars, Kellogg’s, Campbell’s Soup and ConAgra recently decided to label products that contain ingredients from so-called GMOs, or genetically modified organisms. The companies are responding to a Vermont law set to go into effect July 1, which — thanks to an arbitrary, scientifically meaningless definition of “genetic engineering” — will require adding labels to as much as 75% of supermarket offerings. (Many of these contain oils or other byproducts of corn, soy, sugar beet or canola modified with molecular techniques.)

In reality, there is no clear-cut category of GMO food.

In reality, there is no clear-cut category of GMO food, but Vermont’s law mandates “produced with genetic engineering” labels when certain modification techniques have been used on crop plants: “the direct injection of genes into cells, the fusion of cells, or the hybridization of genes that does not occur in nature.” That definition skirts both science and history to achieve nebulous public policy goals.

It’s the use of highly precise and predictable molecular methods of changing or adding plant genes that is the source of so much consternation today. But these methods date back to the 1970s and have been significantly refined since.

At the same time, there is a whole continuum of other techniques for genetically modifying organisms, most of which would fall outside the reach of Vermont’s law.

As a result, labels will appear on an illogical hodgepodge of new and old products that will in no way indicate risk, safety, quality or anything else that is meaningful.

Farmers and plant breeders have, of course, been selecting and hybridizing plants to enhance desirable characteristics for millenniums. A century ago, radiation mutagenesis became a common way to create new plant varieties. That is just what it sounds like: zapping seeds with radiation to scramble their DNA and create mutants, and then cultivating those that exhibit desirable traits. Thousands of popular crops — including lettuce, wheat, rice, oats and the popular Ruby Red grapefruit — were derived this way.

Skeptics of modern genetic engineering might remonstrate that old-fashioned techniques like that are somehow different — more “natural” — because they add no “foreign” genes to the resulting plant. But they’d be wrong about that too.

Since the 1930s, plant breeders have performed “wide cross” hybridizations, in which genes are moved across what were once considered “natural breeding boundaries.” This gives rise to plant varieties that cannot and do not exist in nature. In these hybridizations between different species or genera, the parental plants may be sufficiently compatible to produce a viable zygote, but it won’t survive. To overcome this obstacle, scientists devised mechanical and biochemical ways to “rescue” the embryos and make them viable. Commercial crops derived from wide crosses include common varieties of tomato, potato, oat, rice, wheat, corn, pumpkin and others.

Although they’ve been useful and generally safe, wide-cross hybridizations and radiation-induced mutagenesis represent far more drastic tinkering with nature — and lead to far less predictable results — than the modern molecular techniques used to alter genes.

Paradoxically, neither federal regulators nor pro-labeling activists have evinced any concern about creating new plant varieties with those older techniques. Even though the outcomes would by any reasonable definition be “genetically modified,” they aren’t subject to expensive mandatory testing or review before entering the food chain, or labeling when they are sold.

It is not the source of genetic material, or whether DNA from different organisms are mixed, that should concern us. What is important is the function of the genetic change. Could it, for example, make a plant produce a toxin or become more weedlike? Vermont’s labels don’t make such distinctions. Legislators, regulators, activists and ordinary consumers have had difficulty grasping that “GMO” or “genetically engineered” labels convey nothing useful — or “material,” in the jargon of Food and Drug Administration regulators.

And that raises the question of whether Vermont’s labeling requirement is even constitutional. In a 2015 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that labeling requirements like Vermont’s are “compelled commercial speech” and subject to “strict scrutiny” to ensure they don’t run afoul of the free speech guarantees of the 1st Amendment.

Without some compelling state interest, such as consumer safety or proper usage, Vermont’s requirement to label foods that contain “genetically engineered” ingredients is unlikely to survive the strict scrutiny standard. The Vermont law already has been challenged by a variety of food industry groups, and a decision from the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals could come at any time.

The labeling flap might be dismissed as much ado about nothing. In fact, it is costly and misleading. Activists may believe they are empowering consumers, but in truth they are distracting them from substantive issues such as product quality, safety and value.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. He was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.