A fiery populist and a business-friendly centrist: Contrasting paths toward a Democratic resurgence in West Virginia

West Virginia state Sen. Richard Ojeda, a Democrat, is running for Congress in a Trump stronghold. The former paratrooper and a strong union advocate is harnessing his anger at energy and pharmaceutical companies he argues are getting rich while hur

- Share via

Reporting from Huntington, W.Va. — It is the end of a sleepy holiday week, and sheets of rain flood the roads, but nearly every seat is filled at a town hall hosted by the heavily tattooed man wearing combat boots and seeking to win a congressional seat here.

The turnout would impress the most jaded political consultant. But Richard Ojeda doesn’t have any. That’s probably a good thing. The hourlong riff the blunt-spoken Democrat launches into in this Trump stronghold might have sent the average strategist running back over the hills toward Washington.

The former paratrooper rips into a White House immigration policy that has strong support here in West Virginia’s 3rd Congressional District. He brands coal and natural gas executives as slippery operators. He renounces the belief he held while a soldier that America is the world’s greatest country, saying the poverty and opioid addiction strangling his home state make him ashamed of the nation.

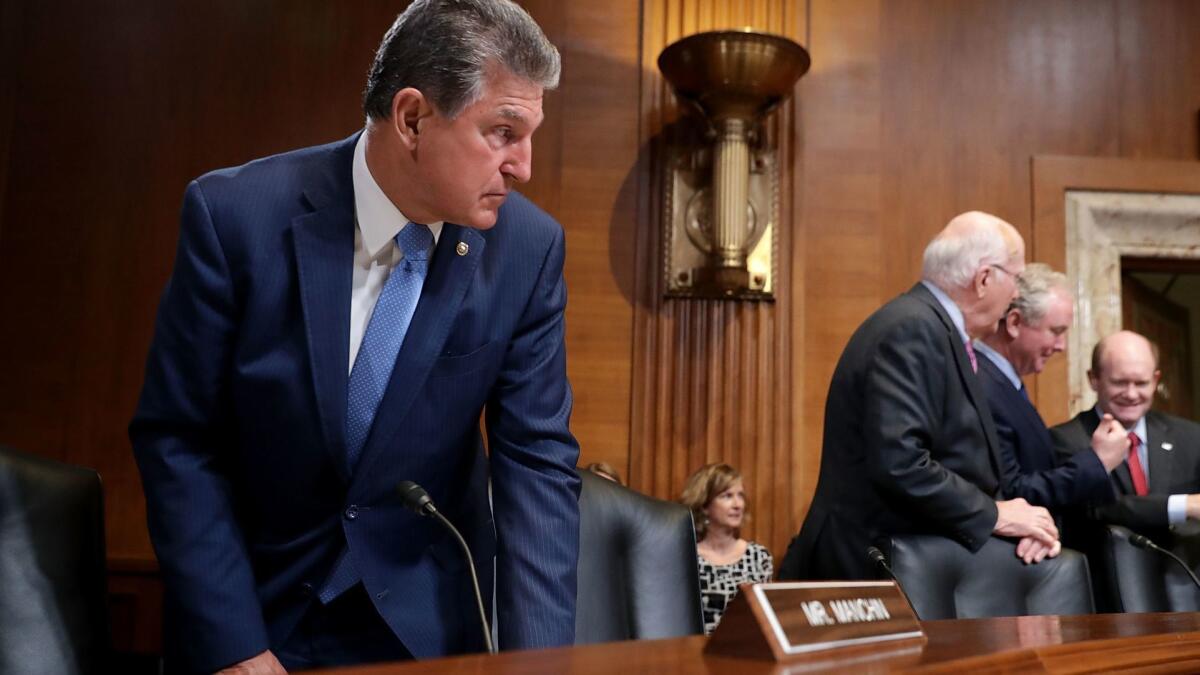

A cauldron of populist anger, the 47-year-old Ojeda breaks most every rule the Democratic consultant class has laid out for winning back coal country. He is nowhere near the playbook of West Virginia’s Democratic U.S. senator, Joe Manchin III, the folksy centrist and on-again, off-again President Trump ally who many in the party see as one of the last hopes for steering Democrats back to power in Appalachia.

But right now, according to strategists in both parties, he’s winning.

Both Ojeda and Manchin are — at least for now — defying conventional wisdom by leading in polls in places where the 2016 election results suggest Republicans should be far ahead. Trump won this state by nearly 42 points. He won Ojeda’s district by nearly 50. A recent poll by Monmouth University showed Ojeda six points ahead of his Republican opponent, Carol Miller. Manchin holds a similarly sized lead in recent polls.

Their campaigns reflect two very different paths Democrats are testing as they seek a way back to relevance in white, working-class communities that abandoned the party for Trump, and where support for the president remains strong.

Both candidates are keenly aware that a poll-tested policy agenda alone won’t cut it here. For all their differences, their campaigns display at least one belief in common: Sharp instincts for the identity politics of the region will be needed to cut Trump’s coattails short in the upcoming midterm. It’s a point that many party activists in coastal Democratic strongholds struggle to comprehend at a time when Democratic candidates feel intense pressure to take up the talking points of the Resistance.

Ojeda voted for Trump. West Virginia politicos generally agree Manchin’s biggest career misstep may have been endorsing Hillary Clinton.

Manchin has spent the last 18 months trying to make amends with his electorate. He endeared himself to Trump enough to warrant consideration for the post of energy secretary. When Trump, instead, nominated Rick Perry of Texas for the job, Manchin introduced him at the Senate confirmation hearing.

Ojeda, for his part, has soured on Trump since the election, but it irks him that party leaders remain perplexed about how a fiery progressive like him could cast a ballot for the New York billionaire.

It’s simple, Ojeda said: The economic vision the Democrats offered for Appalachia was insulting and hopeless.

“You can’t take a coal miner making $95,000 a year, the only work in these parts where you can support a family without having to hold down three jobs at once … and tell them you can make minimum wage or we can give you job training for jobs that don’t exist in West Virginia,” Ojeda said during an interview at his threadbare office in his hometown of Logan.

Sure, he said, Trump’s promises were overblown. “But when one person says we will train you in something that does not exist here, and another person says, ‘I can keep coal alive, I can help you maintain the job making $95,000 a year and help you take care of your wife and children,’ what are you going to do?”

The latest look at the Trump administration and the rest of Washington »

Outside, hundreds of locals wandered among the trinket stalls and carnival acts at the struggling coal town’s annual Freedom Festival. Most of those who stopped to talk with a reporter had three things in common. They work in coal. They are Democrats who support Trump. They adore Ojeda.

“What’s not to like about him?” Trump supporter Kendall Dingess, a 42-year-old coal miner, said about Ojeda as the candidate worked the crowd with a fistful of balloons. “He’s a straight shooter, like Trump. He tells it like it is. There is no bull… .”

Ojeda’s campaign is run entirely by gut. His communications director’s last job was minding the cash register at a Dollar General; his campaign manager is a long-haul truck driver. Yet this grandson of an immigrant who came here illegally — Ojeda says his grandfather helped tend the horses of Pancho Villa’s army before making his way to West Virginia to lay track in the mines — is schooling the power brokers in Washington on the ways of Appalachia.

“This is not about the message, it is about the messenger,” said Robert Rupp, a professor of history and political science at West Virginia Wesleyan College. “He is one of us. Even if voters don’t like what Ojeda is saying, they like where he stands.”

The message is a form of in-your-face populism stylistically similar to Trump’s, but different in the targets of his anger.

“We have to stop letting people come in here and make millionaires and billionaires of themselves off of West Virginia while West Virginia remains poor,” Ojeda said, as he launched into one of his signature indictments of big energy and big drug companies.

“You deploy to other countries and fight this nation’s wars because you have this sense that maybe these people can enjoy what we have in America because we are the greatest. And then you retire one day and you return and realize it was all a bunch of garbage. It was a lie.”

That populism marks a turnabout from West Virginia’s tradition of electing less volatile politicians, like Democratic Sens. Robert C. Byrd, John D. Rockefeller IV and also Manchin, valued for their ability to work within the system. Now, the system no longer works for most voters here.

Ojeda, a first-term state senator, shot onto the radar of labor leaders last year after unflinchingly taking up the cause of West Virginia’s teachers, who went on a strike that rattled school systems nationwide. He is angry that as teachers struggle to pay rent, energy companies eager to extract the state’s massive deposits of natural gas balk at an extraction tax that could be used to boost their pay.

As his community reels from the opioid crisis, he says to any politician “helping or protecting big pharma while they are killing our people, you are a murderer.” He blames feckless legislators beholden to drug interests for delaying implementation of a medical marijuana law Ojeda muscled through the Legislature.

In his own, more measured way, Manchin is also seizing on healthcare. The potential unraveling of the Affordable Care Act by Republicans and a more conservative Supreme Court is a key campaign issue for him in a state where 800,000 people have preexisting conditions, and most of them can’t afford insurance without government help.

“If insurance companies can go back to playing the games they played before, they can decide the fate of most of West Virginia,” Manchin said Wednesday at a Washington conference held by the Economic Innovation Group. “Whether they can buy insurance, afford insurance or whether they are one illness away from catastrophic ruin. These are the things we deal with.”

But the senator made clear his frustration with his own party, a theme that plays well at home. He recalled how Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) asked him after Trump’s election, “What happened to the West Virginia Democrats?”

“I said, ‘Not a thing. They want to know what happened to the Washington Democrats,’” Manchin said.

When the ringing of his mobile phone interrupted Manchin, fellow panelist Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) joked that the caller was probably Trump. Not skipping a beat, Manchin replied that it probably was.

Manchin, who is running for reelection against West Virginia attorney general Patrick Morrisey, is sitting on an impressive campaign war chest. Money is a bigger problem for Ojeda. His race against Miller, a wealthy Republican legislator expected to have considerable resources, is fast becoming a test case of how far modern grass-roots fundraising can take an unconventional candidate.

Help has also come from an unexpected place: Silicon Valley. Last year, as his campaign got underway, Ojeda found himself at a Palo Alto wine bar, pitching his vision to tech innovators at an event sponsored by the People’s House Project, a political action committee established by the journalist Krystal Ball to boost working-class Democrats running for office. Ball worked with Rep. Ro Khanna, the Democrat who represents much of the Silicon Valley, to introduce Ojeda to the tech world.

“That trip was unbelievable,” said Ball. “Richard had been all over the world with the military, but he had never been to California. He got in a room with these tech lawyers and entrepreneurs and executives and said, ‘I don’t know why you don’t think we have smart people in West Virginia.’

“These were progressive people who saw themselves as open-minded and not bigoted. They realized they had a lot of stereotypes about what West Virginians are like.”

Khanna, who has been travelling to coal country in an effort to build economic and political alliances, said Ojeda has a message the rest of the party should listen to.

“We default to the same platitudes and talking points people have been running on for the last 20 years,” the congressman said in an interview. “Party leaders can learn from [Ojeda]. Here is someone doing well in a part of the country where we have not been doing well.”

More stories from Evan Halper »

evan.halper@latimes.com | Twitter: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.