Genetically modified cells learn to fight mesothelioma

- Share via

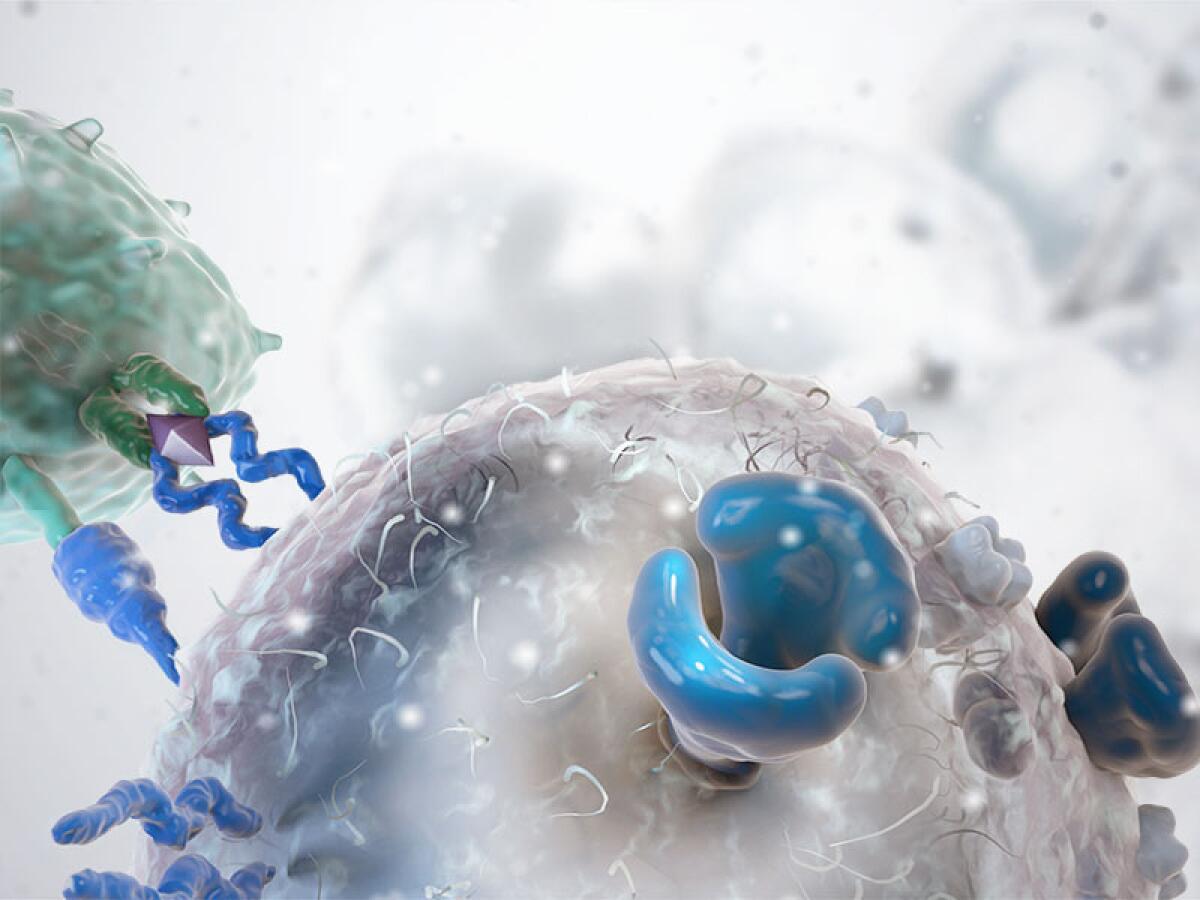

It’s been called the “fifth pillar” of cancer treatment: genetically reengineering the human immune system to recognize cancers and fight them.

The treatment has shown recent promise in fighting blood cancers such as leukemia. But hard tumors, such as mesothelioma, have proven to be more resistant to attack from these tinkered T cells when they were reinjected into the bloodstream.

Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York tried delivering the modified white blood cells directly to the tumor area, and found that they not only eliminated the cancer, but proliferated and persisted, successfully fighting off a reintroduced cancer. Their work was published online Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine.

The study, using human T cells and tumors in a mouse, helps pave the way for phase one clinical trials in humans. Pending approval from the Food and Drug Administration, such a safety trial could begin early next year, said lead researcher Dr. Prasad Adusumilli, a thoracic surgeon and member of the Center for Cell Engineering at Sloan Kettering.

About 2,500-3,000 people are diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma annually, often after exposure to asbestos, according to the American Cancer Society. But tumors that arise elsewhere, such as the breasts, pancreas or ovaries, often spread to the space around the lungs, known as the pleural cavity, where mesothelioma strikes.

“For whatever reasons, cancers tend to go there and I wanted to target that,” said Adusumilli.

The researchers tried both intravenous injection and introducing the rejiggered T cells into the pleural cavity of the mice.

“Surprisingly, what we found is the moment T cells go there, they see the enemy – the cancer cell – they activate themselves and they activate other T cells and they proliferate,” Adusumilli said.

The method was successful even with a dosage as much as 30 times lower than an intravenous dose, and even 200 days later, after a tumor was reintroduced, according to the study.

For more than a decade, researchers at Sloan Kettering, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and other institutions have experimented with genetically altering T cells to produce a receptor matched to the antigens on tumor cells.

Last month, researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported that 27 of 30 patients with advanced, recurring leukemia were in remission after their T cells were modified and reintroduced.

But four years ago, a patient died after such therapy apparently induced acute lung inflammation.

Adusumilli said it’s possible that administering the engineered cells via chest catheter, rather than intravenously, could bypass such side effects in the lungs. That and other factors will be tested in the clinical trial.

Get your dose of science. Follow me on Twitter: @LATsciguy