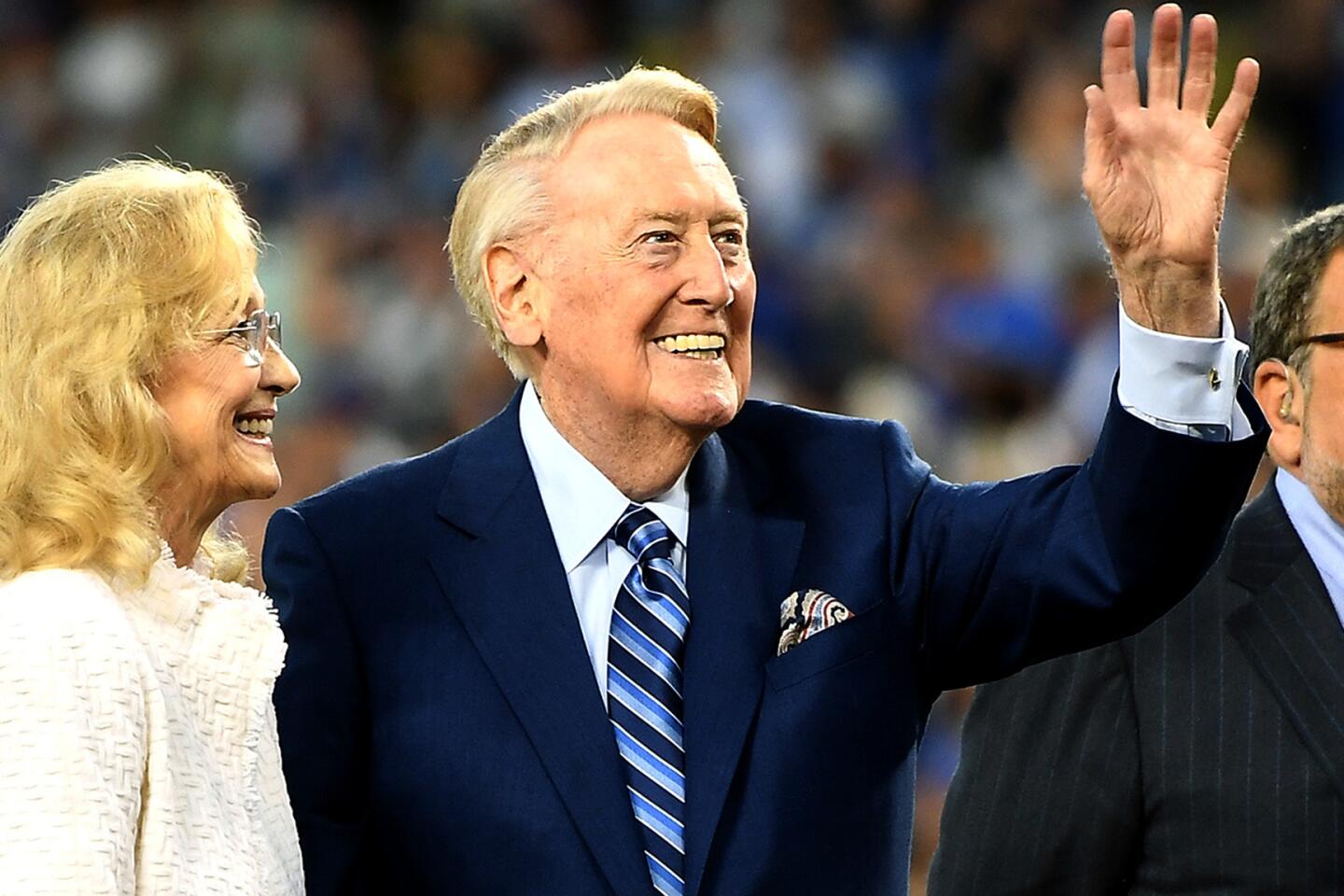

Vin Scully’s support team is thankful for the memories of working with a master

- Share via

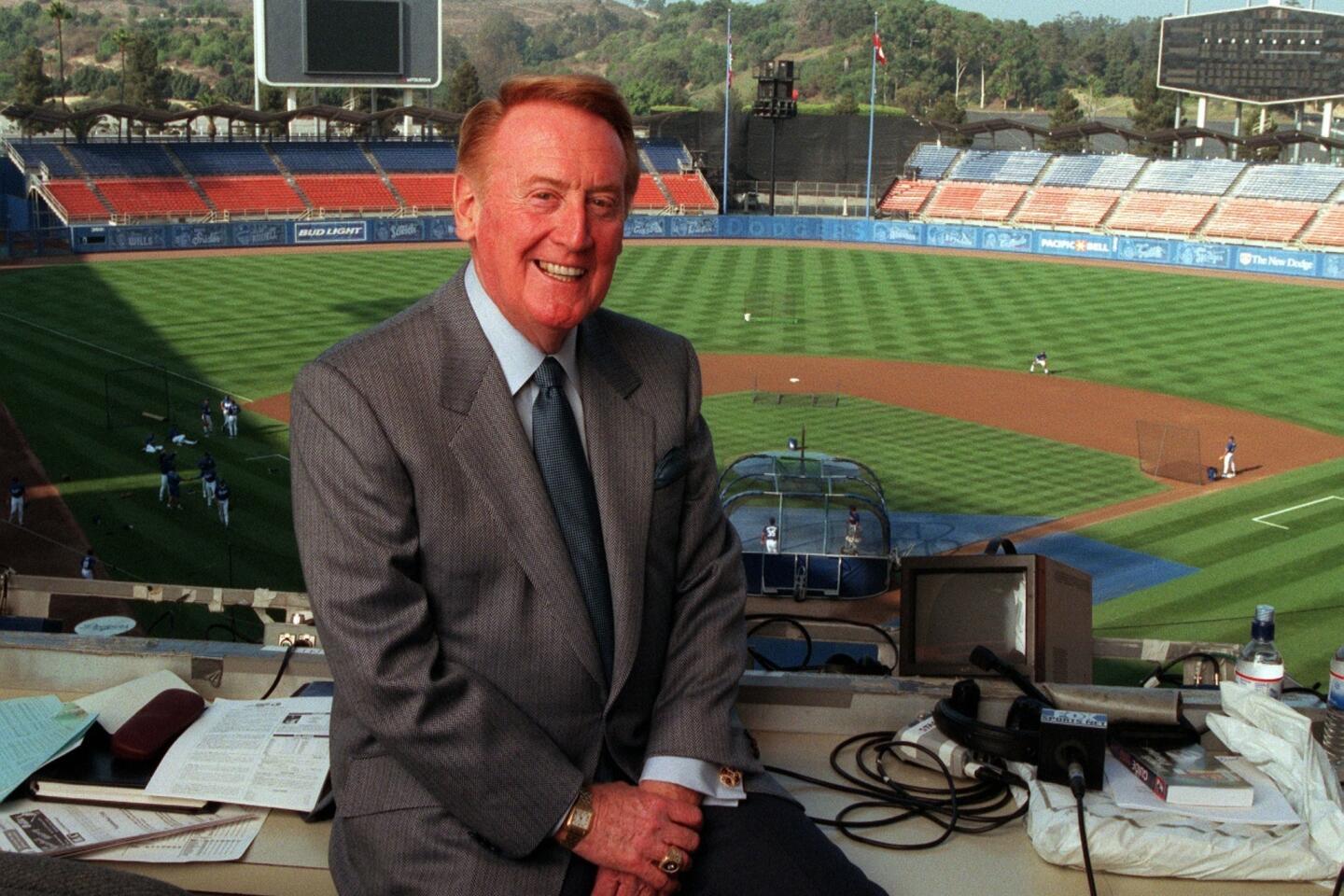

Listen to Vin Scully tell a story over the radio or television and it’s as if he is talking directly to you.

More likely, the person he was actually speaking to was Brian Hagan, a 56-year-old statistician who sits in the second row of the television broadcast booth.

When Scully shares an anecdote, he often does it with his chair turned toward the back of the room, his eyes locked with Hagan’s, taking an occasional glance over his shoulder to track the action on the field.

“He has to have an audience,” Hagan said, “and I’m the one who’s least busy.”

Hagan laughed. “Magical,” he said.

Hagan is the junior member of Scully’s support team, which also includes stage manager Boyd Robertson and camera operator Rob Menschel.

If the countdown to Scully’s retirement has marked an emotional period for fans, imagine what it’s been like for this group. They have worked alongside Scully night after night, game after game. Many of the stories or statistics he recites on the air come from them. They have a feel for the kind of information he likes, as well as how and when he likes to receive it.

Robertson and Menschel are in their 28th seasons working Dodgers broadcasts. Hagan is in his 10th full season.

Scully values the consistency they offer, which is why he has made it a point to keep the group together whenever the Dodgers have changed broadcast partners.

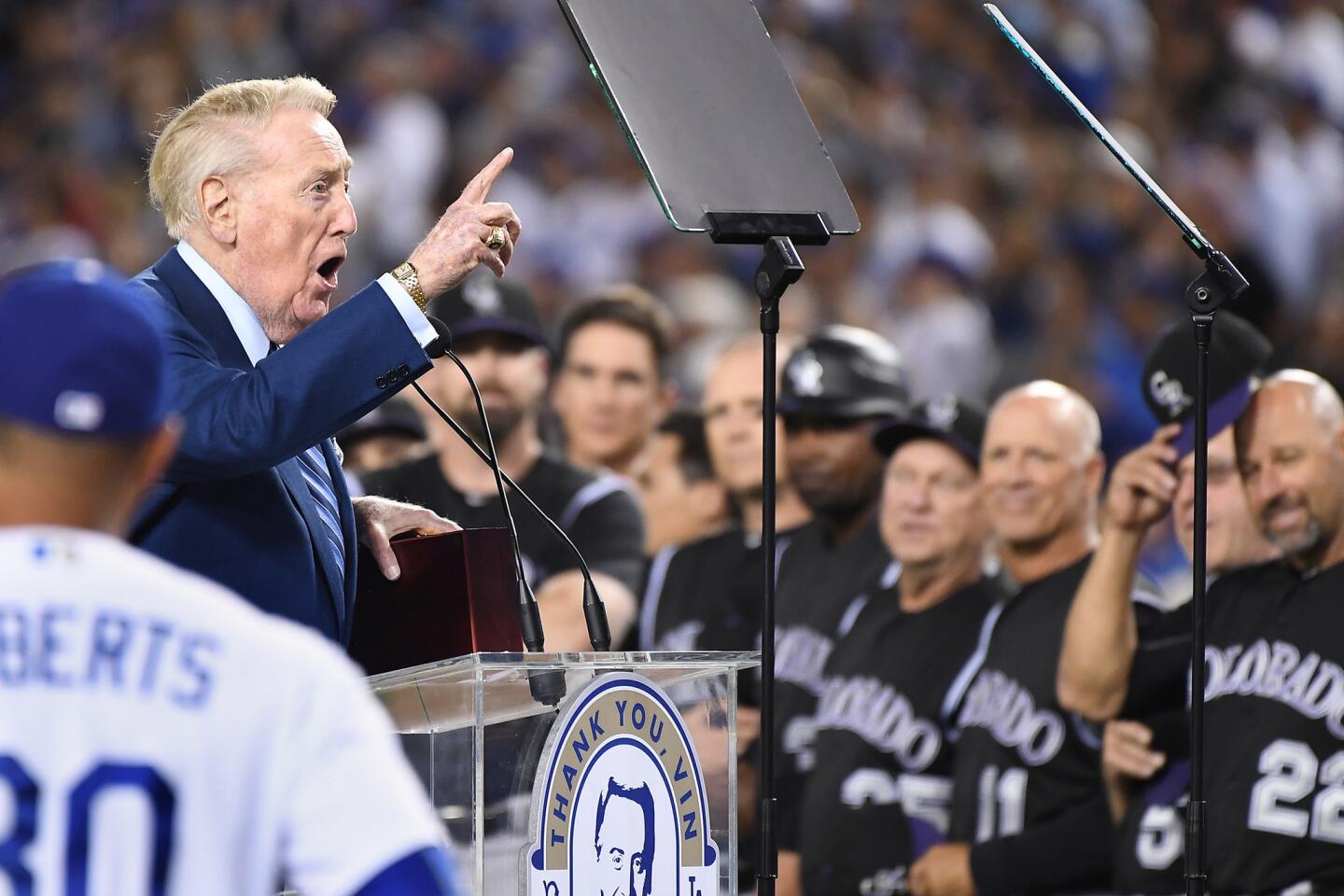

“The pinnacle of my professional career,” said Robertson, who has also worked with Bob Miller, Tom Kelly and several other big-name broadcasters.

Robertson and his colleagues are delighted Scully will be able to retire when he wants and how he wants.

Even so, “It’s obviously bittersweet,” Menschel said.

Working with Scully changed their lives. How Scully treated them changed how they viewed themselves.

Robertson was a nervous wreck when he showed up to work with Scully for the first time, on opening day in 1989. The Dodgers were in Cincinnati.

Robertson introduced himself. “I’m Boyd Robertson, Mr. Scully,” the Oklahoma native said.

Scully replied, “If we’re going to work together, it’s Vin.”

Anyone who has met Scully has a similar story, but it remains one of Robertson’s favorites.

“He was putting me at ease,” Robertson said.

Robertson was proudest whenever he heard Scully refer to him as his “sidekick.”

Hagan also counts his initial interactions to be among the most important moments of his life. “I don’t have a lot of confidence,” he added.

He was born in New York but moved to Southern California when he was 12. He listened to Scully almost every night on the radio and played baseball as a child, but didn’t try out for his high school team.

Hagan started working with Scully in 2006 as a fill-in for statistician Doug Mann.

One of his first games was future All-Star Chad Billingsley’s major league debut. The game was in San Diego.

“I was scared to death,” Hagan said.

As was the case with Robertson, Scully knew what to say to him. When the game ended, Scully turned to Hagan and told him, “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Scully wasn’t talking about Billingsley. He was talking about how Hagan was able to find some obscure statistics for him to use.

“I was flying,” Hagan said. “I flew home from San Diego and I didn’t have an airplane.”

Hagan joined the crew full time the next season.

Scully did more than build the crew’s confidence. He also taught his assistants how to work.

Chick Hearn knew that would be the case. That’s why when Robertson told him he had a chance to be Scully’s stage manager, Hearn encouraged him to do it, even though it would require him to miss some Lakers broadcasts.

Robertson worked with Hearn for 15 years.

Overlapping work schedules never allowed Scully and Hearn to become well acquainted. But listening to Scully, Hearn was certain Robertson would learn something from him.

Robertson found out the two broadcasting legends had something in common: They came to work prepared.

“Every day is a learning experience,” Menschel said.

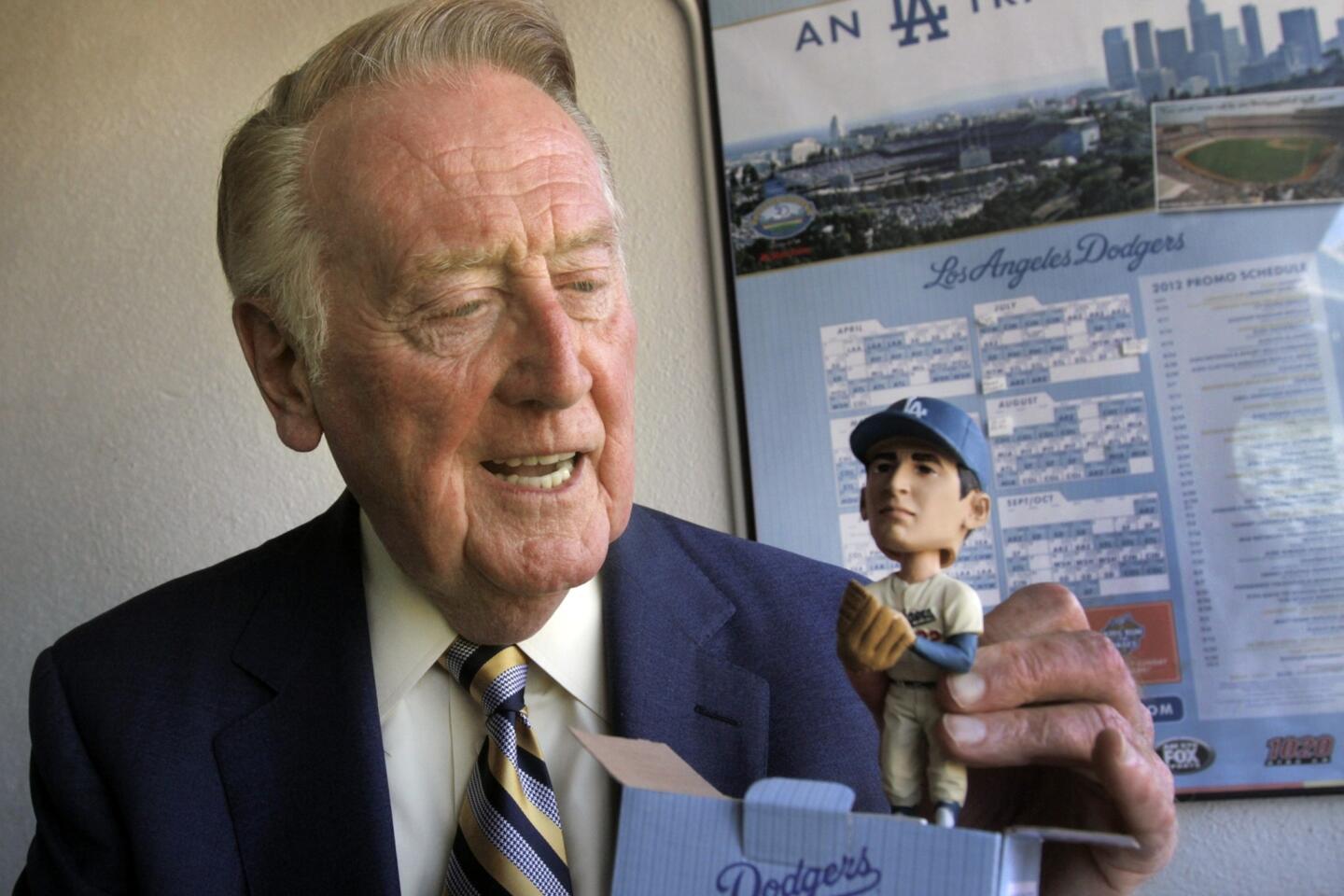

Scully does a substantial amount of his own research. He reads newspapers and magazines.

If he finds something he can use that day — or maybe even in a couple of months, if it pertains to an out-of-town player — he will clip the article and set it in a binder. He has a binder for every team.

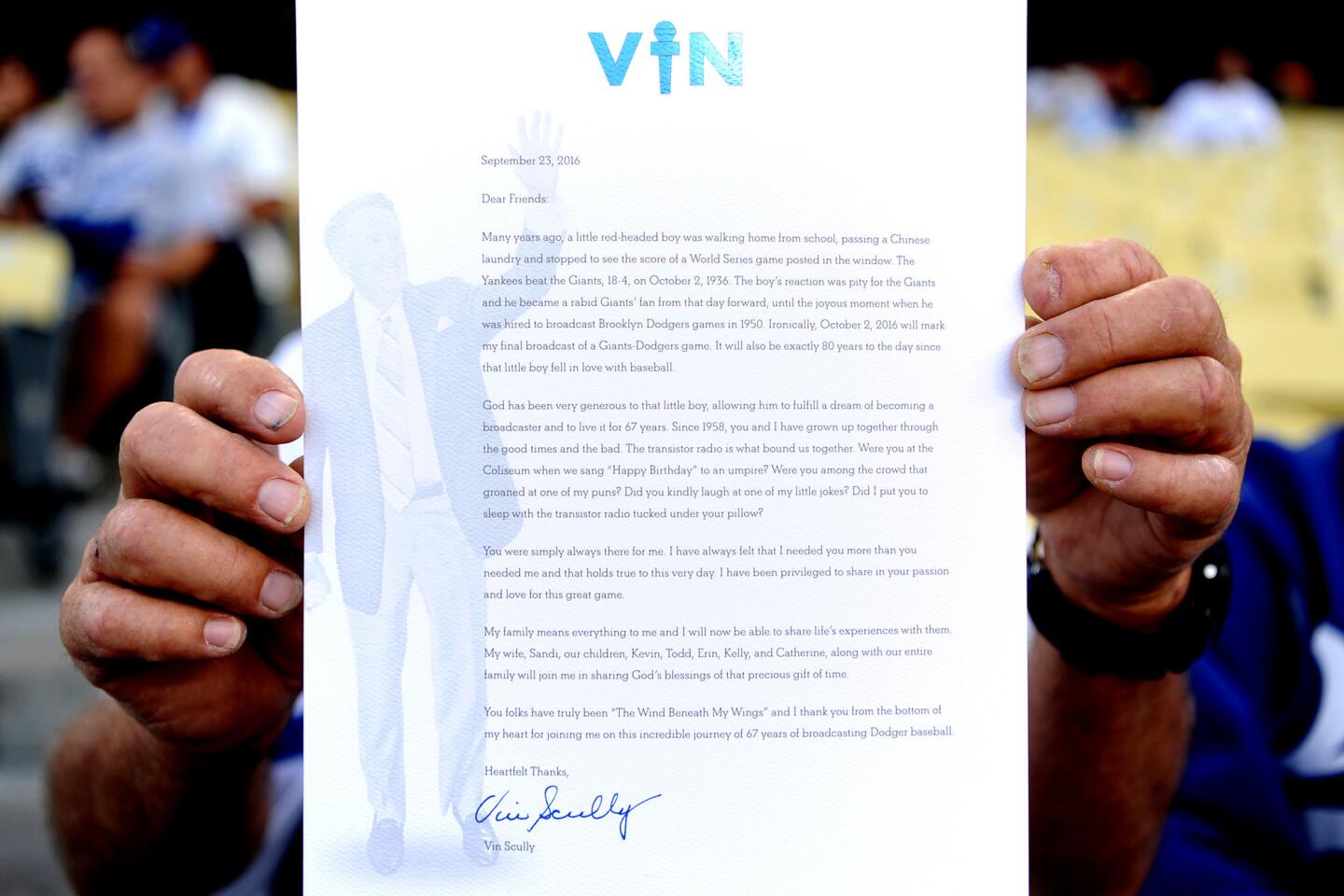

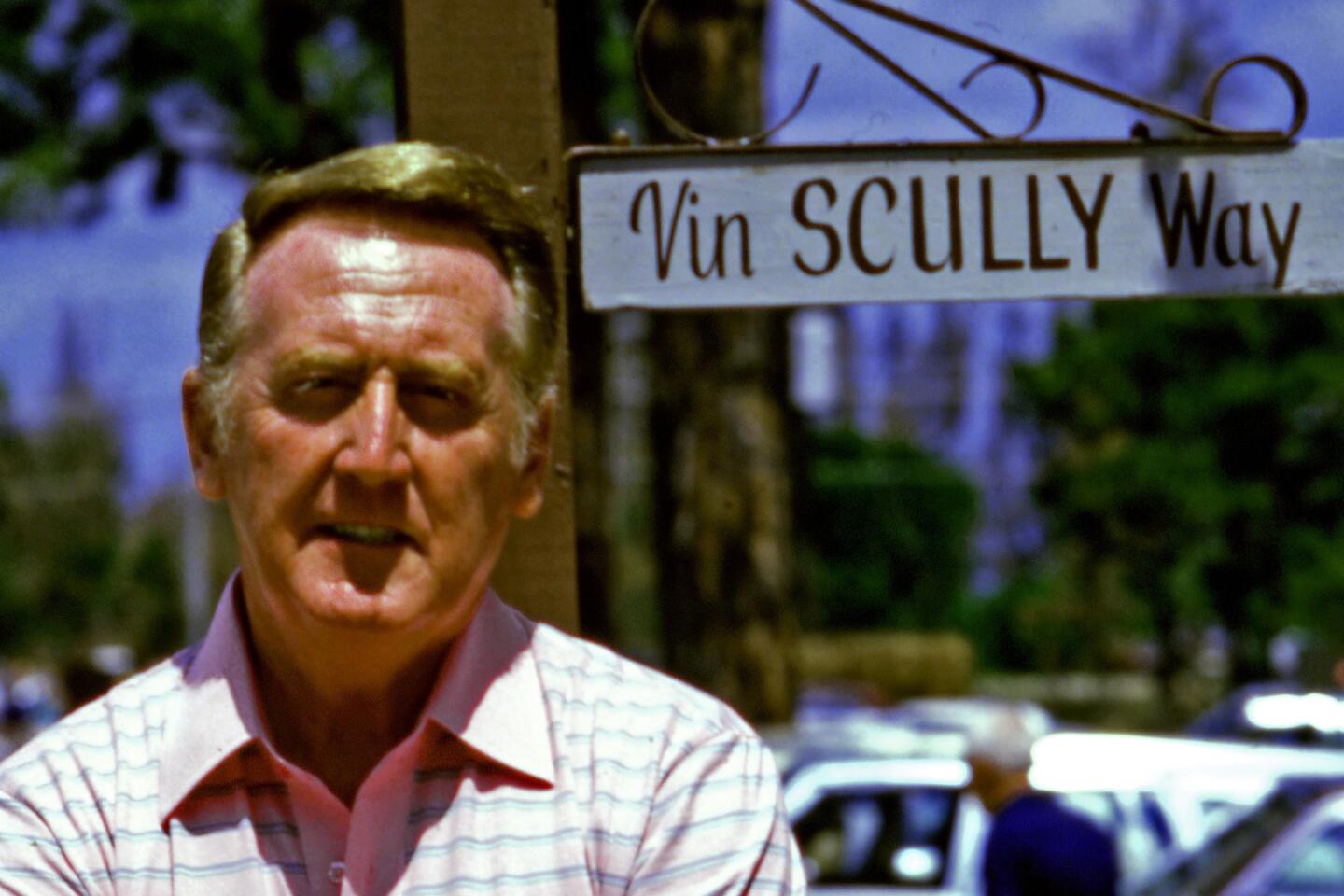

Scully, 88, doesn’t limit himself to traditional forms of media. He used to travel with a laptop computer. He later upgraded to an iPad. He also owns a smartphone.

Menschel said he has heard Scully use the word “Google” — as a verb.

For a 7 p.m. game, Scully will meet with Robertson and Menschel about 3 1/2 hours before the first pitch to map out the night. He might ask them to look something up. Or he might want to know the start times of games that could affect the Dodgers’ place in the standings, so he can plan on when to provide his listeners with updates.

Whatever their intentions, the group improvises once the game starts.

Scully sits in the front row, on the far left. Robertson, who is the liaison between the booth and the television truck, is next to him. On Robertson’s right, Menschel handles a camera.

Hagan, a row behind, sits next to audio engineer Dave Wolcott.

While they are on the air, they communicate with hand signals. As the game unfolds, Robertson, Menschel and Hagan will pass notes to Scully, usually on an index card.

They estimate their contributions make the air about 20% of the time. They marvel at how Scully can read a card while speaking, digest the information and seamlessly incorporate it into the broadcast on the fly.

“If it’s out of left field, I probably had something to do with it,” said Menschel, who, like Scully, was born and raised in New York.

Bill Plaschke discusses the magic of Vin Scully’s words and silence after Kirk Gibson hit a home run in the World Series.

One of Menschel’s favorite moments this season was when Scully informed his viewers that Boston Red Sox outfielder Mookie Betts was named after former NBA player Mookie Blaylock.

“A light went on in my head,” Menschel said.

Menschel started to write notes on a card.

Moments later, Scully said on the air, “Do you remember when Mookie Blaylock was the original name of the group called Pearl Jam?”

Scully continued, “Their legendary debut was titled ‘10.’ That was Blaylock’s uniform number.’”

Scully chuckled and said, “What made it so very interesting, in the album, ‘10,’ they have 11 songs.”

The reaction on social media was instantaneous.

“Twitter went ballistic,” Menschel said.

Menschel, Robertson and Hagan remain awestruck by how Scully always seems to be able to complete a story before the end of an inning.

“He’ll be the first to tell you, ‘Don’t start a story with two outs,’ but he always does it,” Menschel said.

Whenever he does, nervous glances are exchanged within the group.

This is going to be the time, they think. Except the baseball gods always seem to intervene; four consecutive pitches will be fouled off and Scully will finish his story before the inning is complete.

Robertson said that what appears to be divine intervention is more a reflection of Scully’s ability to adjust at a moment’s notice.

“He’s off-the-charts smart,” Robertson said. “He edits the story as he goes along. He can stretch it out or he can shrink it.”

What amazes Robertson, Menschel and Hagan the most is how he has treated them.

“Live television turns people into monsters,” Hagan said. Except Scully, who doesn’t yell over mistakes.

“We had a window,” Hagan said, “to something so beautiful.”

dylan.hernandez@latimes.com

Twitter: @dylanohernandez

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.