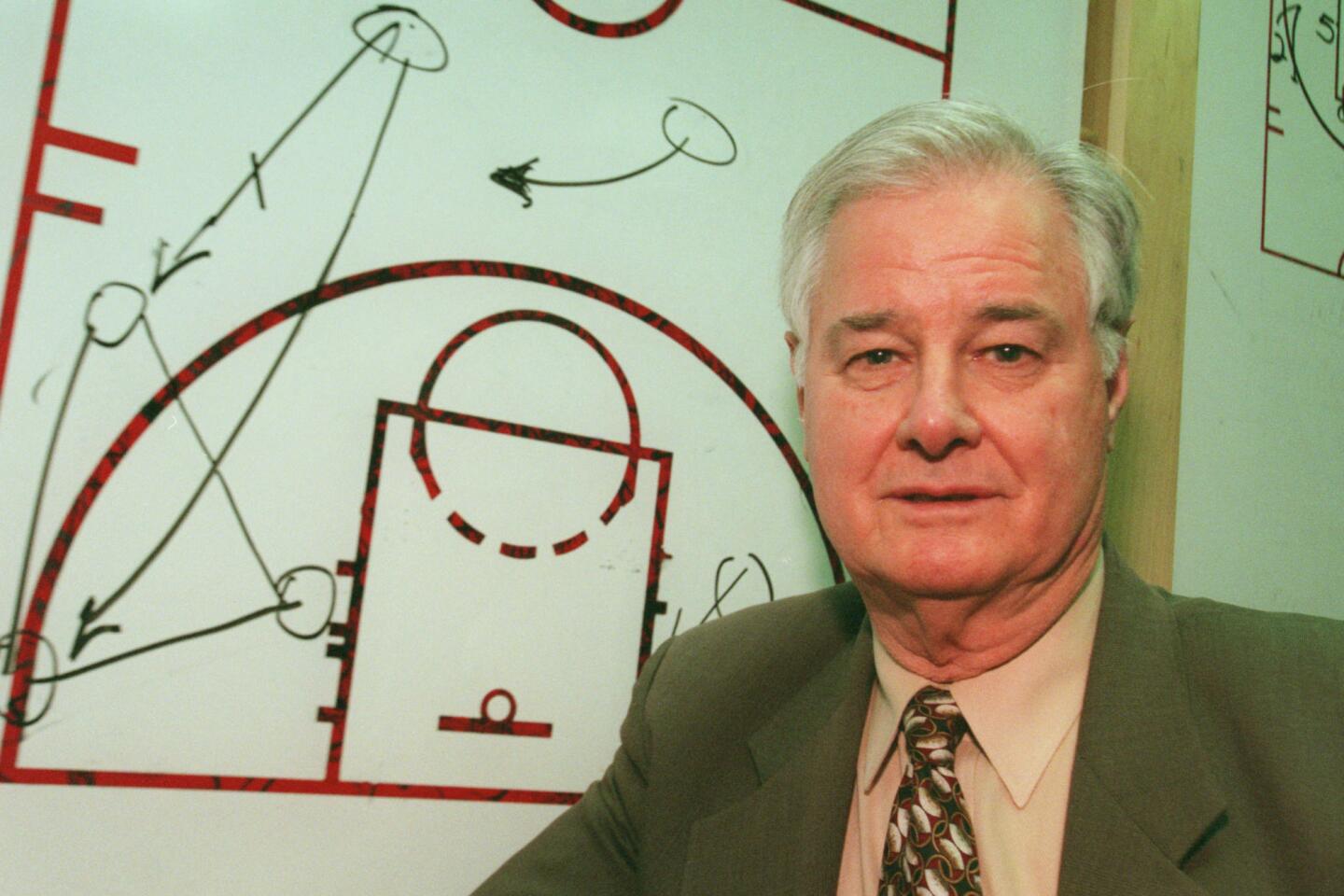

Appreciation: Tex Winter was about more than the triangle offense; he was a stickler for details

- Share via

Michael Jordan, the greatest shooting guard in NBA history, moved with an incredible fluidity. The quick shake of his shoulders, a wiggle of his hips, a tilt of his head could all leave defenders helpless.

The same can be said for Kobe Bryant — the closest thing to Jordan that has ever existed — a guard who could spin around and slice through whatever a defense put in his direction.

And Shaquille O’Neal, a player bigger, quicker, more agile and stronger than any other center in the league, couldn’t be stopped by anyone. Just throw him the ball and get out of the way.

The three players had the talent to do whatever they wanted, to ignore gravity, to shrug off double teams, to put teammates on their backs and out-talent anyone unlucky enough to be put in front of them.

It could be individualism at its finest, the will of one man meaning more than anything or anyone else.

And it was absolutely not to Tex Winter’s tastes. His system required more than the greatness of one.

“It’s like five fingers in a glove,” Winter once said of his preferred offense.

Basketball, for Winter, was more structured and more basic. A man standing in the post, a man in the corner and one with the ball weren’t three individuals. It was a triangle — and it became the defining principle for a generation of NBA basketball.

The Chicago Bulls and Jordan won six titles running Winter’s favorite offense. The Lakers won five utilizing his system. That’s 11 titles over a 20-year span.

Winter, who was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2011, died Wednesday at the age of 96.

“He was a master of the triangle,” O’Neal said. “I liked to go out of the triangle every now and then, but, he would just convey the message that it works and we’d sit and watch film and he had to say, ‘Sometimes you have to be not Shaq the dominant guy, you got to be like a decoy, get others involved.’”

Winter’s legacy extends beyond the offense. He coached all over the country — Marquette, Kansas State, Washington, Northwestern and Long Beach State at the college level. He trained himself to become a top-class pole vaulter at Compton Community College. He was a pilot in the Navy and a guard on the basketball team, playing for Chuck Taylor, later known for his association with canvas sneakers.

It was a Forrest Gumpian existence — interesting places at interesting times — but the final half of his career, as an assistant to Phil Jackson with the Bulls and Lakers, put him at the epicenter of professional basketball, with the game’s most talented players doing things his way, even if it was reluctantly.

“The better the basketball player is, the more you might expect that they might not want to accept it because it involves … it’s a team concept,” Winter said during a 1992 Bulls broadcast. “It involves giving up the ball.”

Beyond the offense, those who played for and coached with Winter remember him as being obsessed with details. The corners of the triangle? They should be 15 to 18 feet apart. Rebounds should be grabbed with two hands, and passes should be thrown with two as well.

“He was a stickler for everything regardless of the situation,” former Lakers forward Robert Horry said. “You could be up 20 and he still wanted you to run stuff to the T. We just thought it was funny and crazy. It’d be like the last five minutes of the game and he’d be arguing about something, like, ‘You need to do this.’ I’ll give him this: He knew his stuff about basketball. With him, you couldn’t have a break sometime.”

Winter had an obsession for the fundamentals — a word he repeated almost constantly when people remember his contributions to basketball.

“Tex Winter was a basketball legend and perhaps the finest fundamental teacher in the history of our game,” said Bulls executive vice president John Paxson, who played for Winter. “He was an innovator who had high standards for how basketball should be played and approached every day. Those of us who were lucky enough to play for him will always respect his devotion to the game of basketball.”

He could help improve players’ footwork, shooting form and body positioning. He couldn’t, Winter would tell his team, do the rest.

“There’s no replacement for effort and energy,” former Bulls guard B.J. Armstrong said. “I can remember him always telling us that.”

The offense itself is still controversial in some corners — was it simply put into the hands of some of the best basketball players ever or was it the best possible system to turn players such as Jordan, Bryant and O’Neal into champions.

Neither Jordan nor Bryant ever won a championship running a different offense.

He was direct with his players. Armstrong said that Winter asked him for his permission to coach him honestly and truthfully.

“Tex was the best coach of all time and he was going to keep it real,” former Bulls and Lakers guard Ron Harper said. “I can recall when he saw me my first year with the Chicago Bulls, then in my second year he told me, ‘I thought you couldn’t play basketball anymore.’ That’s what he told me. … After we won the championship, he said, ‘You have proven me definitely wrong.’ He said, ‘I told Phil you were washed up. You proved me wrong. … You gave me everything I asked and I want to tell you man to man that you proved me wrong.’

“I said, ‘Tex, I got nothing but love for you, because you were motivation for me to get to where I needed to get to.’ That’s one thing Tex would always do, he would keep it real.”

Winter never wavered from the foundation of his philosophy.

“Basketball is a game of geometry,” he said.

The court is a rectangle. The ball is a sphere. The rim and net form a cylinder. And an offense, when run properly, will produce triangles.

In 2009, a stroke robbed Winter of nearly all of his ability to carry on a conversation. (When asked to sketch plays, he would still grab a pen and draw a triangle.) At his Hall of Fame induction, one of his sons, Chris, spoke for him, trying to share his father’s philosophies.

“If you have something to offer, offer it,” Chris Winter said. “If you have something to give, give it.”

For some of basketball’s best talents, Winter offered a chance to play team basketball, a chance to win, a chance to be one finger inside the glove.

Those fingers, thanks to the triangle and to the man who taught it best, now have championship rings on them.

Staff writers Broderick Turner and Tania Ganguli contributed to this appreciation.

Twitter: @DanWoikeSports

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.