Pakistan villagers flee military offensive, harsh militant rule

- Share via

Reporting from Bannu, Pakistan — For the tribespeople of North Waziristan, fleeing their homes amid a Pakistani military offensive was in many ways like escaping a torture cell.

Islamist militants had roamed through neighborhoods with impunity, villagers said. They collected taxes, controlled the streets and routinely detained and abused anyone they suspected of espionage, with no interference by Pakistani security forces stationed nearby.

“Virtually the entire government’s administrative system had collapsed,” said one man who fled to the town of Bannu. Like many displaced residents, he declined to give his name for fear of reprisals.

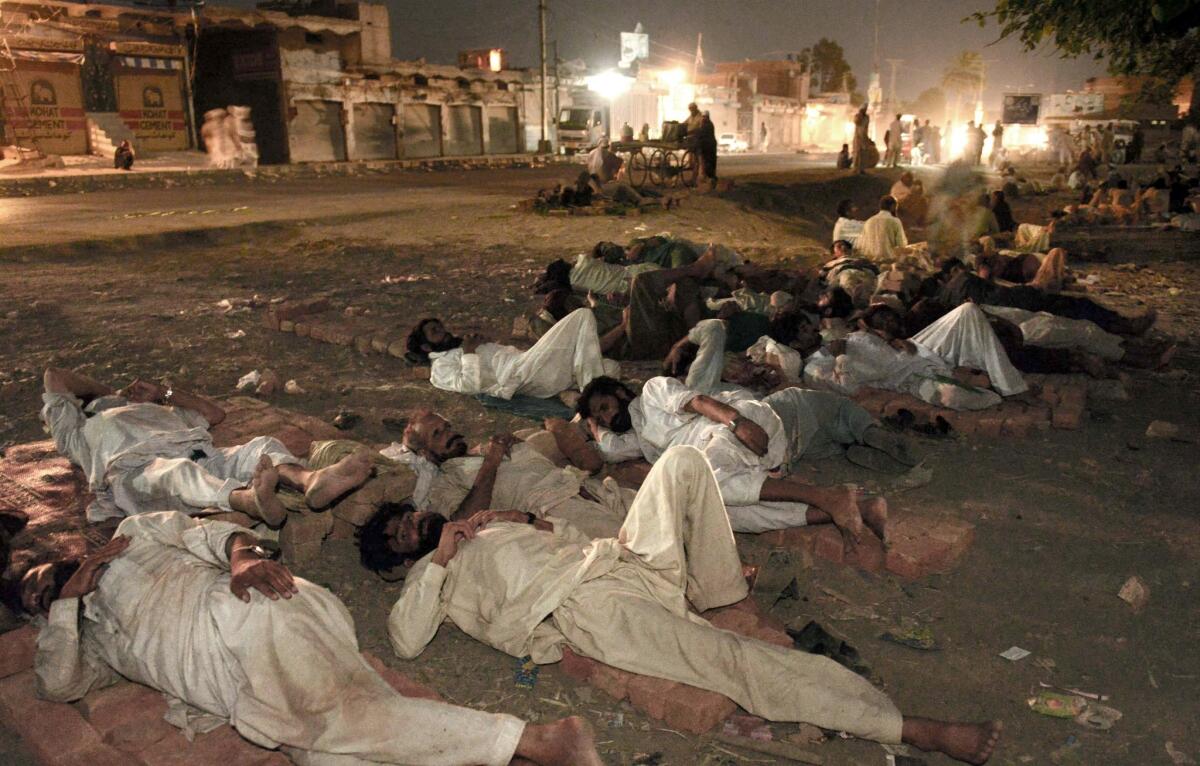

Since June 18, the Pakistani military has bombarded the North Waziristan tribal area in an operation that officials say has flushed out militants responsible for attacks on both sides of the Pakistani-Afghan border. It has also sent 1 million residents, most of them women and children, fleeing to other parts of Pakistan or to Afghanistan, overwhelming local authorities and international aid agencies.

Maj. Gen. Asim Bajwa, a Pakistani military spokesman, said Tuesday that more than 400 Pakistani and foreign militants had been killed and that soldiers had destroyed dozens of bomb-making factories and confiscated large quantities of explosive material from Miram Shah, the regional capital. Twenty-six soldiers have been killed, according to military officials, who have declined to specify how long the operation will last.

North Waziristan is in effect sealed off to outsiders, but many villagers believe that, as with previous operations, top militant commanders left the area before the bombings began. The offensive had been in the offing for several months as the Pakistani government’s attempts to engage the insurgents in peace talks collapsed, and even some military officials acknowledged that militants had time to flee.

“The fact of the matter is, the leadership at the moment is not present in the areas where we have carried out the operation. If they were, we would have apprehended them,” Maj. Gen. Zafarullah Khan, an army commander in the tribal region, told reporters last week at a briefing in a cantonment in Miram Shah.

Commanders said they had cleared militants out of Miram Shah, but many experts believe the most powerful insurgent leaders slipped across the border into Afghanistan, where they may be responsible for a recent increase in insurgent attacks coinciding with the country’s presidential election.

The Haqqani network, which has been behind some of the deadliest attacks against U.S. forces in Afghanistan, has been untouched by the Pakistani offensive, said C. Christine Fair, a Georgetown University professor and author of “Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War.”

The array of militant groups that found a haven in North Waziristan includes the Haqqanis, the Pakistani Taliban, Arab extremists loyal to Al Qaeda, Uighurs opposed to the Chinese government and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. Many began pouring into the area after a 2006 army operation against militants that ended in a cease-fire.

Activists say that despite the truce, the militant groups quickly reorganized and were joined by a flood of fighters from Russia, Central Asia, Germany, China, Turkey and European countries, many of whom came to fight U.S.-led forces in Afghanistan.

“The nightmare started when the Taliban, along with Arabs, Uzbeks and other foreigners, poured into the area after the army conducted the 2006 operation,” said Gul Wazir, a political activist in Bannu, a town at the edge of North Waziristan.

Some tribesmen tell of how militants enjoyed free rein in the towns and villages, with the Pakistani security forces mainly confining themselves to a small garrison in Miram Shah. The militants started off friendly, cracking down on a gang of criminals in Miram Shah and winning residents’ sympathies. Many fighters married local women.

“We never thought that they would become monsters,” Wazir said.

Even in the relative safety of Bannu, where hundreds of thousands have taken shelter in recent weeks, many villagers were hesitant to discuss the extent to which militants had taken over the rugged Pakistani-Afghan border.

Some said that fighters with the Pakistani Taliban collected taxes from drivers for transporting goods to and from North Waziristan, while security forces did nothing to intervene. As part of their parallel government, the militants developed an extensive intelligence network and regularly arrested and executed people they believed were passing information to the U.S. or Pakistani governments, residents said.

“A big worry of the militants … was that local people would spy on their activities,” said one man who said he was detained for three months in 2010 on suspicion of spying for Americans in Afghanistan.

He said he was held in one of several small cells in a large compound somewhere in North Waziristan, his hands and feet bound with steel chains. He denied spying and was released after three months, but a friend was killed in militant custody, he said, his body later found on a road, riddled with bullet holes.

The task of rooting out spies largely belonged to the fearsome Khorasan Group, described by experts as the intelligence wing of the powerful Pakistani Taliban faction led by Hafiz Gul Bahadur. These well-trained fighters often went barefoot, their faces covered with black cloth, with a black band around their heads that read, “God is great,” residents said.

The Khorasan Group had its own torture cells and detention centers where an unknown number of civilians were killed. The group recorded confessional statements by those accused of spying. Beheaded bodies were found hanging from trees, bearing warnings not to bury them for three days, contravening Islamic custom.

A doctor who said he had treated fighters said the militants devised new techniques to terrorize residents. One morning he saw 29 human heads placed in a row outside the government hospital in Miram Shah, opposite a security base. Later, militants began kicking the heads, he said.

“I have never seen such a horrific scene in my life,” he said.

Special correspondent Ali reported from Bannu and Times staff writer Bengali from Mumbai, India.

For more news, follow @SBengali on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.