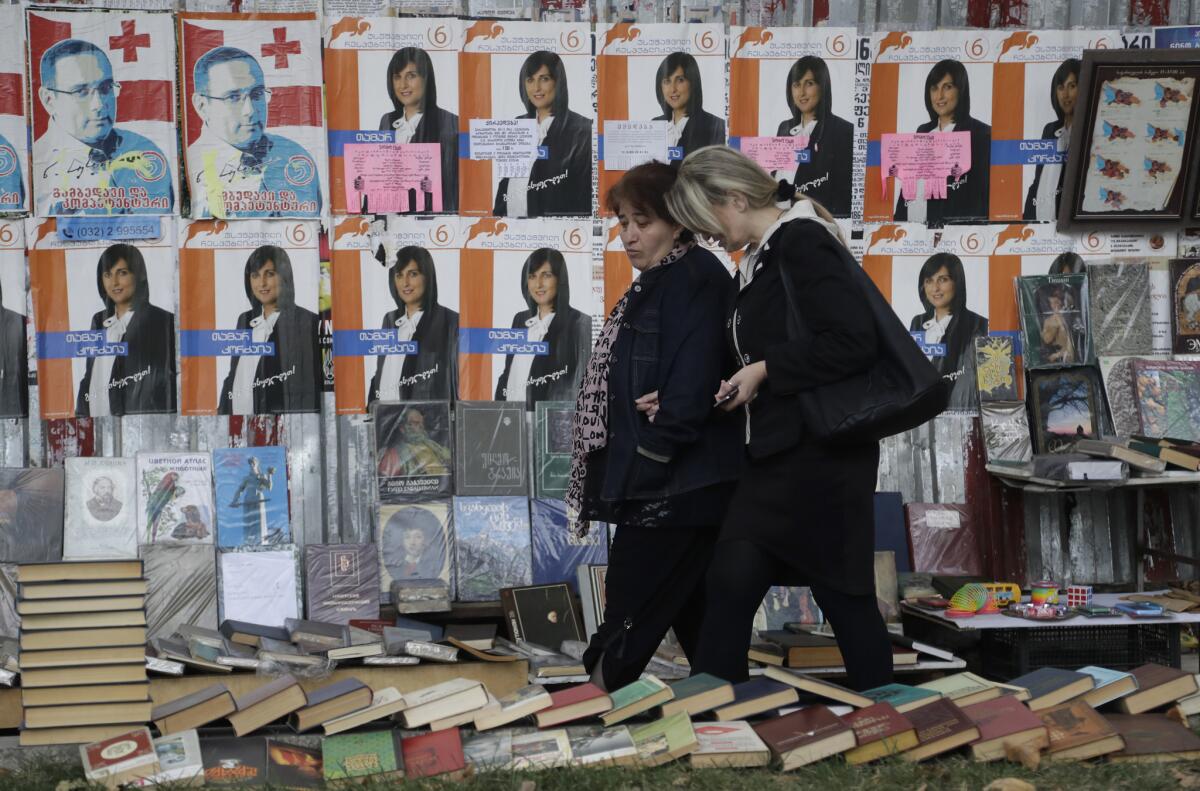

Will Putin get his way in neighboring Georgia? Elections test how far Russia radiates its power

- Share via

Reporting from Tbilisi, Georgia — It captured just about 5% of the vote, but an ultranationalist party has won enough votes to join the Georgian parliament for the first time, presenting a challenge to the two pro-Western parties that have dominated the country’s politics.

The sounds of election night victory reverberated across the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, late Saturday as supporters of the ruling Georgian Dream party honked car horns and proudly waved their party’s blue and yellow flag in the heart of the city.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Oct. 10, 12:50 p.m.: This article misidentifies Gutsa Gvelesiani and incorrectly transcribes her comments about election gains made by the Patriotic Alliance, a pro-Russian party. Gvelesiani is a member of an advisory office on NATO issues, not a Georgian representative to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. While referring to support of the Patriotic Alliance from Russian President Vladimir Putin, she was quoted as saying: “All I can hope for is that they don’t care at all about actually governing. They’ll just take Putin’s money and disappear.” Her quote should read: “My hope is that they don’t know anything about actual governing and they’ll lose [the next election]. Anyway, it [their support] is all from Putin’s money.”

------------

The incumbents reportedly captured between 40% and 54% of the vote, with the main opposition party, the United National Movement, or UNM, garnering upward of 32% of the ballots cast, according to various unconfirmed news reports.

The ultranationalist Patriotic Alliance, meanwhile, has tapped into the growing discontent with the West, and initial exit polls indicate that the alliance and other pro-Russian parties made significant gains in Saturday’s election

“It looks as though for the first time since the Soviet Union we will have several small pro-Russian parties in the national government,” journalist Tamar Svanidze said.

Georgia’s political culture is defined by a rough and tumble character and corrosive brand of personality-driven politics.

This year’s campaign season has been no different, with televised punch-ups, incriminating sex tapes, assassination attempts and coup plots.

After breaking free from Moscow’s orbit following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Georgia spent the next decade mired in a self-destructive cycle of civil wars, reprisal killings and rampant organized crime.

It was not until Mikheil Saakashvili led the 2003 pro-democracy Rose Revolution that Georgia began to turn the corner.

As president, Saakashvili quickly implemented several key reforms that overhauled the country’s economy, but those early advances were slowly undone by what many Georgians described as unhinged behavior.

Following an ill-advised war with Russia over the breakaway region of South Ossetia in 2008, the West’s support for Saakashvili dried up, though the former president still remains leader of the UNM.

Georgian Dream, led informally by its founder, billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, unseated the UNM in 2012, but the overwhelming majority of Western-educated Georgians view Ivanishvili with extreme skepticism, polls show.

Ivanishvili’s close association with Russian businessmen worries many Georgians as he guides the country down a more Moscow-friendly path.

Georgian Dream’s dismal handling of the struggling economy, which has scared away many foreign investors, and Ivanishvili’s lavish spending on eccentric vanity projects has angered the population.

“A lot of people in this country are looking for a savior … but what is important is that we don’t have another Misha [Mikheil] Saakashvili. The [Georgian Dream] may not be doing a lot, but it isn’t a party of dictators who arbitrarily arrest and kill people,” said Ia Giorgadze, a classically trained musician.

Though the UNM and Georgian Dream publicly bicker, the two agree that Georgia must pursue eventual integration into the EU and NATO military alliance.

But the process of Euro-Atlantic integration has been painfully slow, and Brussels has thus far failed to grant Georgia visa-free access to the EU. NATO has sent mixed signals in the hope it does not provoke Russia, despite frequently stating that it fully supports Georgia’s goal on joining the alliance.

Angry and disillusioned, a significant part of the electorate has turned to fringe ultranationalist parties with close ties to the Kremlin. The parties have been backed by a robust media presence that spouts anti-Western propaganda.

This has played into the Russian narrative that post-Soviet republics mean little to Western governments and should stay closely tied to Moscow.

Russia has coveted Georgia’s strategic position on its southern flank, by the Black Sea and Turkey, for three centuries, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has been waiting for an opportunity to bring the country back into Moscow’s orbit.

The Patriotic Alliance is known for its xenophobic, anti-Western rhetoric, and its platform claims to “uphold traditional Orthodox values” and rejects women’s and LGBT rights.

Its leader, Irma Inashvili, hopes to block Georgia’s moves toward joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

“The emergence of the Patriotic Alliance and now its likely representation in the next government is a disaster for the country. I am shocked, truly shocked,” Gutsa Gvelesiani, a Georgian representative to NATO, said.

“All I can hope for is that they don’t care at all about actually governing. They’ll just take Putin’s money and disappear,” she added.

Fringe pro-Russian parties like the alliance are seen as viable alternatives for Georgians with a deep nostalgia for the Soviet Union and are supported by radical members of the powerful Georgian Orthodox Church.

Led by the elderly former KGB informant Patriarch Ilia II, the church is helping to steer the country toward an open embrace of the “Eurasianist” doctrine espoused by Moscow Patriarch Kirill and Putin’s chief ideologist Alexander Dugin.

Georgia’s newly elected parliament will find itself at a major crossroads.

It can no longer rely on guaranteed Western support the way that it could more than a decade ago.

The question moving forward for the new government will be whether archrivals the UNM and Georgian Dream can bridge their differences and caucus with other pro-Western parties to reverse Putin’s most recent gains.

Waller is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Rival Syria resolutions by West and Russia defeated at U.N.

Moscow welcomes the (would-be) sovereign nations of California and Texas

Putin suspends deal with the U.S. on weapons-grade plutonium disposal

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.