Missing Link, Teamwork Mean Success for Inventors

- Share via

SCHENECTADY, N.Y. — History books frequently picture a scholar toiling in a laboratory year after year until--Eureka!--a sudden idea or an unexpected explosion produces a revolutionary invention.

But it rarely happens that way.

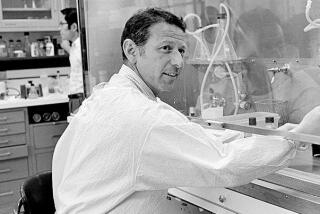

The act of invention is closer to the process of evolution and an inventor is more like a missing-link specialist than an overnight genius, according to Charles Eichelberger, an inventor following in the footsteps of Thomas Alva Edison at the General Electric Research and Development Center.

52 Patents Eichelberger has 52 patents ranging from a television camera the size of a wristwatch to a process that allows electronic circuits to be printed on glass, paper, steel and other materials. Someday he could be portrayed as a man, like Edison, who shook the world with his inventions.

Or that reputation could go to one of his 1,200 colleagues at the center, or his grandfather, William E. Paul, who also worked as a GE inventor and retired with 34 patents, including a circuit breaker used in power plants to help prevent blackouts in cities.

The Research and Development Center, started in 1900 in a barn, now produces roughly a third of the 600 or so patents GE obtains annually.

It is the workshop of a broad-based collection of researchers and inventors dabbling in virtually every scientific discipline, from biology to physics. In addition to inventions concerning appliances and lighting, the facility has created man-made diamonds, bullet-proof plastic and X-ray equipment.

Improved Products From places like this, consumers and industry get their new and improved products. Ideas from people like Eichelberger make the products possible.

“It’s always my aim to have the results of my work become a commercially viable product,” he said. “That’s the key to invention.”

Edison, the founder of GE and the most prolific inventor in U.S. history, had more than 1,000 patents. He developed, among other things, the phonograph and the motion picture camera, but he’s best remembered for the light bulb. But who remembers John Howell or William Coolidge, inventors who helped turn the innovation into a profitable product?

“Edison deservedly got all his names on the patents, but many of his ideas were either from someone else to begin with and he improved them, or they were his idea but they really wouldn’t have been workable and someone else improved them,” Eichelberger said.

Edison Team He said Edison managed to fill in “an awful big missing link,” but he also had a team of scientists working with him.

More than 100 years ago, Alexander Graham Bell said: “Watson, come here; I want you,” and earned credit for discovering the telephone. It’s not as widely known that Bell combined the existing technology of the telegraph and the musical telegraph for his invention, or that Edison improved upon Bell’s original creation.

“I get a lot of inspiration from Edison and Bell . . . and other well-known inventors,” Eichelberger said. “It’s great to think of inventing that way, but I think that in this day and age the problems are almost always so complex that the invention requires a team.”

Eichelberger, 39, said he gets many of his initial ideas “during long showers.” He hones the ideas by talking with other scientists or inventors in the center’s cafeteria.

Productive Snack Over a coffee and a danish, he can sometimes accomplish more than spending weeks in his laboratory.

“I really think the idea of the solitary inventor has pretty much gone by the wayside,” he said. “Anything that is significant in this day and age is going to require a team of people to really bring it to market.”

An example is his wristwatch-size TV camera, which is used to give factory robots sight and is mounted on telescopes to track the movement of distant stars.

While eating lunch, Eichelberger, who was working on ways to expand computer memory, sat down with two scientists who were working with radar. Listening to what they had done gave Eichelberger the missing link that led to the tiny camera, which was then refined by other scientists at the center.

“There are also times when I know of someone doing work in a particular field and can call them up or just walk down to their office, and very often from those meetings and discussions will come a new idea,” he said.

The discussions sometimes involve absurd solutions to problems or the “Rube Goldberg approach”--a roomful of electronics to power a thumbnail-size radio, or appliances that might require X-ray equipment in the basement or perhaps a neutron accelerator.

“We joke about the absurd solutions, but you boil them down and sometimes can find a few elements of worth,” said Eichelberger, who joined GE in 1968 after graduating from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in nearby Troy, N.Y., with a master’s degree in electrical engineering.

His father, who died when Eichelberger was 5, was a GE accountant, and his mother was a computer programmer for the company.

Grandfather Nurtured Talent

But his grandfather, who helped rear him, was the man responsible for nurturing Eichelberger’s talent.

Today Eichelberger is helping create new products and sometimes a whole new business for one of the largest companies in the country.

That was the case with a chemical process that allows electronic circuits to be printed on various materials. GE plans to sell special inks and instructions on the process.

Eichelberger’s latest creation probably will have the biggest visible impact on the nation. He has devised an electronic converter that will allow cable television companies to broadcast on twice the number of channels without having to lay new cables or change existing equipment.

Individual Filter In addition to doubling the number of channels, the converter lets a cable company filter individual channels for individual customers on a daily, even hourly, basis.

In a building with three apartments, each with the same cable service, one could pay to watch a boxing match on a particular day, while the apartment below could pay to watch a movie at the same time and the third apartment could receive a ballet.

The “addressable converter” box is expected to be put on the market sometime next year, for sale to cable television companies, Eichelberger said.

With 16 years of experience as an inventor, Eichelberger said: “I always used to think . . ., how could that guy have ever thought of that? But then you find out that he was working in the field, he knew what everybody else was doing, and what he found was the missing link.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.