Medical Team’s Car Safety Crusade Helps Save Lives of Children

- Share via

EL TORO — Fran Antenore had the first suspicion that something was amiss about 7:30 p.m. one Friday early in June, 1981. That’s when she walked into the family’s Modjeska Canyon home and found everything dark. Her husband, Jim, and son Jeff, not quite 2, should have been home, with lights on and dinner ready.

Then the phone rang.

Would she come immediately to the emergency room at Saddleback Community Hospital? Her husband and son had been in a car accident. Jeff, the caller said, seemed pretty much OK, but Jim had leg and head injuries.

“My knees sort of went out,” Fran said. “I had to call a neighbor to take me to the hospital.”

When she got there, Jeff did appear OK. But her husband was still incoherent; it would turn out his ankle was broken, his knee was torn apart and his head injuries would result in a hearing loss on one side.

The two had been on their way home from school; Jim teaches social sciences at Irvine High School and had picked up Jeff at a day-care center.

Jim was driving the family van along a particularly bad stretch of old El Toro Road, a spot where there was a 90-degree turn, with construction along the side; Jim was observing the speed limit and taking special care.

Then a young man coming the other way in a car decided to “pass three cars at once,” Fran said. The driver made it past the three cars but was unable to slip smoothly back into line, said the Antenores. The car hit the dirt at the side of the road, careened back onto the pavement, and slammed into the Antenore van.

Jim, who had been wearing a seat belt, was pulled from the van unconscious. Jeff, who had been strapped into a well-anchored child’s car seat, wound up with a bruised arm and bits of glass in his hair, but basically unhurt.

What if they had not been wearing those restraints? Jim, who now considers himself back in pretty good shape in spite of the pin in his knee and some remaining hearing loss, shakes his head. “If not, I don’t know if we would be here.”

Not surprisingly, the Antenores --who always believed in buckling up--are ardent supporters of car restraints. When parents don’t belt in their youngsters, Jim said, “it really borders on criminal behavior, endangering the child.”

“By the way,” Jim asked his visitors, “did you buckle up today?”

There’s urgency in the voices of Phyllis Agran and Diane Winn as they point out that automobile accidents are the No. 1 cause of death and injury among children from 1 to 14 years old, and as they tell the stories:

- The child who fell out of the moving car, even though there were four adults riding in the same vehicle; the child was run over by the car and killed.

- The 3-year-old riding on his father’s lap, the so-called “child crusher position,” while the father was driving . . . and after he plowed into a water tank, doctors found an imprint of the steering wheel on the dead child’s chest.

They have other stories, equally searing. “Unrestrained children in vehicles are essentially unguided missiles,” Agran said.

Shortly after a picture of the Antenore accident appeared in the newspaper, Agran, a pediatrician who practices at the UCI Medical Center and Childrens Hospital of Orange County, wrote a letter to thank the paper for mentioning that Jeff was in a car seat.

For Agran, concern about the safety of children riding in cars had begun when she was a medical student training in the emergency room.

She watched as young children were brought in after car accidents, and she was distressed to discover that most of them--an estimated 80%--had not been wearing restraints.

Though Agran did not continue working in the emergency room after receiving her degree, she never lost her concern for those youngsters--or her determination to do something about them.

Eventually, she formed a team, including Winn, a registered nurse who holds a master’s degree in public health, and Debora Dunkle, a Ph.D. and research specialist, to launch what has become a five-year project.

It has turned into a home-grown, Orange County effort to make a difference in child safety.

The team lobbied hard for passage of a bill requiring that children under 4 or lighter than 40 pounds be belted in--and saw it become state law Jan. 1, 1983.

They also worked to gather the kind of facts that would be convincing to legislators when the time came to seek future legislation --facts that would prove restraints make a difference.

Sponsored in part by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and California State Office of Traffic Safety, the team went fact-gathering at nine Orange County Hospitals.

They sought to show that the law had actually gotten youngsters into car seats, and that more restraints would mean fewer injuries and fewer deaths.

They checked how many youngsters brought to the hospital following accidents had been wearing restraints--and compared those figures with results of earlier studies at the same hospitals.

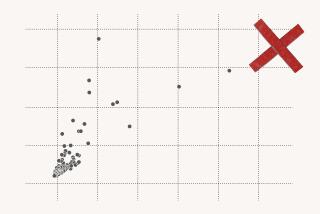

They found that restraint use was up: Car seat use for infants under 1 jumped better than 20%, from approximately 32% in 1982 (just before the law) to 55% in 1983; use by children age 1 to 3 rose from about 25% to 45%.

And, the team determined, a higher percentage of youngsters involved in accidents survived without injury in 1983 than had the year before.

They got good news, too, from the California Highway Patrol, which reported the number of injuries among children covered by the law has gone down--even though the number of children in that age group actually is up.

The team made one other interesting discovery: Use of restraints within the county had surged the previous year (1982) as well, not long after a child restraint education program was introduced by the Orange County Trauma Society.

That group, headed by Shirley Gower, began working with hospital obstetrical departments in May, 1981, encouraging them to educate new mothers about car restraints. The society soon began renting out car seats--even giving them to some mothers who could not afford them. Then they developed a preschool curriculum featuring puppets named Buckle Bear and Belt Man.

An Early Problem

One early problem, Gower said, was to convince everyone involved that new mothers should not ride home cradling newborns in their arms. Even health personnel at first “thought we were crazy,” she said. “They would say, ‘You can’t put a newborn in a car seat.’ ” But now “all 21 obstetrical departments in the county are very cooperative,” Gower reported.

The pediatrician, obviously, is pleased with the success so far. But she has more plans down the road.

For one thing, she would like to get older youngsters into the seat belt habit--perhaps by extending the law to cover youths to age 14. Figures clearly show that older children never have used restraints as much as younger ones, and that they lag even further behind now, Agran said.

“Parents are relatively good about restraining the young ones,” Agran said. “Then, with increasing age, these kids start to get difficult to deal with, and by the time they are old enough to handle themselves in the car, they are mostly not restrained at all.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.