His Real Estate Deals Prove Embarrassing to U.S. Judge

- Share via

While preparing to preside over the John Z. DeLorean drug trafficking trial, U.S. District Judge Robert M. Takasugi got word that he might have to stand trial himself.

Takasugi was named as defendant in a civil lawsuit that arose from his investments in East Los Angeles real estate.

It was a small matter--a workman accused the judge of failing to pay $6,600 for repairs on a house.

But its backdrop was an embarrassment.

Behind the suit stood the judge’s 20-year business relationship with a real estate broker, Jaye Marshall Uribe, whose reputation was as bad as Takasugi’s was good.

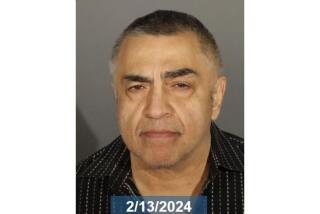

Uribe, who arranged for the workman to do the job, was known as an indiscriminate betrayer of trusts. He was known as that to his son, to his attorney, to his childhood friends and to assorted others who said they had painfully concluded over the years that he was unscrupulous or worse.

Uribe was also Takasugi’s partner and friend.

Irony was inescapable.

Takasugi was known, as one attorney put it, as “a defender of justice with a capital J.”

Conspicuous Sympathy

Perhaps because he had spent much of his boyhood in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II, he became a man who, as a judge, displayed a conspicuous sympathy for the underdog.

The judge supplemented his income by trading in real estate with Uribe.

Theirs was a small enterprise--one that Takasugi now calls “stupid.”

Uribe, who has been ill in recent months, declined to be interviewed for this article.

According to Takasugi, Uribe would spot Eastside houses for sale. Takasugi would supply money to buy them. Uribe would arrange to fix them up, rent them out and sell them. Then they would divide profits.

Takasugi said he owned only three to six houses at a time, and participated in an average of only one transaction a year.

But that didn’t stop Uribe from using the judge’s name.

Uribe displayed in his office a photograph of himself and the judge, and sometimes dropped Takasugi’s name to convince his own clients that he could be trusted, former associates said.

Judge’s Name Used

When those who claimed he had victimized them demanded their money back, Uribe would also use the judge’s name, without the judge’s knowledge, to scare them into dropping their claims, said the broker’s son, Jaye Mark Uribe:

“He would say, ‘I don’t have the money. It’s Bob’s money. He’s a federal judge.’ ”

Even so, Uribe was sued frequently.

In court papers he denied any wrongdoing.

Civil and default judgments piled up against him in suits alleging that he defrauded a widow in the purchase of a house, wrongly persuaded another widow to sell her house through him even though an escrow had already been opened for another buyer, took a client’s down-payment money but failed to apply it to the purchase price of a house, unlawfully refused to return a deposit on a house that Takasugi owned and failed to pay a workman who had labored on the same Takasugi-owned house.

Takasugi, who said he had no knowledge that Uribe was using his name and almost no knowledge of the suits, appears to have benefited from some of Uribe’s questionable deals.

For example, Takasugi apparently got part of a $35,000 loan that Uribe obtained on the strength of a document that, according to a handwriting expert and the supposed signer, was a forgery.

The loan, for which Takasugi co-signed, was made in early 1983 by a firm called Zenith Home Loan. To obtain it, Uribe put up as collateral a South El Monte house that Takasugi had deeded to him. The questioned document came into play when a hitch developed just before the loan went through.

Mechanic’s Lien Discovered

Zenith’s title company discovered that a mechanic’s lien had been placed on the property by the same workman who later sued Takasugi. The workman said he was owed $5,800 for repairs.

Because the lien ate into the value of the collateral for the loan, Zenith balked at making the loan.

But Uribe produced a document, purportedly signed by the workman, releasing the lien, Zenith officials said. Zenith then approved the loan.

Part of it went to pay $11,000 Takasugi still owed on the property, the officials said. And Takasugi said he also received about $17,000 from Uribe for deeding the property to him.

But the workman insisted he still had not been paid. He said his name on the document was a forgery.

The workman, Marcelo Reyes, was apparently convincing. Zenith’s title company wound up paying him for his work.

The Times retained an independent handwriting expert, John J. Harris, former president of the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners, who concluded that the workman was correct--the signature was not his.

Takasugi said he knew nothing of the document. “It doesn’t make any sense for me to jump on something for a lousy $16-$17,000,” he said. “Forgery of a document that I would--oh gosh, no.”

In other questionable dealings in 1983, Takasugi apparently had thousands of dollars worth of repairs made on three of his houses at a discount by another workman who claimed he was exploited by Uribe.

This workman, Miguel Gonzales, speaks only Spanish and gave this account through an interpreter:

Gonzales was a tenant of Uribe. Uribe agreed orally that Gonzales and his son would make repairs on various houses in lieu of rent.

Then Gonzales became a tenant of Uribe’s mother, and Uribe changed the agreement. He said that the Gonzales family would have to pay rent to Uribe’s mother, and that he--Uribe--would pay Gonzales separately for repairs.

Gonzales showed receipts indicating that rent was paid regularly in accord with a written agreement.

But he said Uribe paid him and his son only $3,200 for work on three of the judge’s houses in 1983, rather than an agreed-upon $7,700.

No Money or Credit Given

When Gonzales sought credit for his work or money for it, he was given neither. Gonzales said Uribe told him: “You don’t have proof that I owe you anything. . . . I do have proof. I have a rental contract.” Gonzales did not pay that month’s rent.

Uribe’s mother, the owner of record, went to court and succeeded in evicting the Gonzales family for failure to pay the rent.

Takasugi said he knew nothing of the workman’s woes.

In a third instance, Takasugi obtained a Pico Rivera house in late 1982 with Uribe’s assistance. The owner of the house says he was duped by Uribe.

Land records show that Takasugi acquired the house by foreclosing on Uribe’s interest in it.

Uribe had obtained his interest in 1981 by foreclosing on a trust deed that the owner said Uribe had pressured him to sign on a promise that it would not be recorded.

The deed secured a loan that the owner, Joseph T. Aguirre, a former Uribe employee and childhood friend, said had never been made.

In legal papers, Uribe claimed the loan had been made.

The owner’s story was partly corroborated by Uribe’s own lawyer at the time, James C. Cupp, who said that he had asked Uribe for proof that the former employee owed him money but that Uribe had not been able to provide any.

Takasugi said he knew nothing of this.

He said he had no idea that he had foreclosed on Uribe’s interest in the house. He said Uribe had led him to believe that the deal was an outright purchase.

Shown a copy of a land record that bore his signed name and authorized a step necessary to the foreclosure, Takasugi said the signature on the document was not his.

Harris, the handwriting expert retained by The Times, concluded that Takasugi was correct.

But the document was notarized by Uribe, who swore that Takasugi had in fact signed it in his presence.

Takasugi said he had not given Uribe permission to sign the document for him.

When Takasugi was told of the details of these transactions during a lengthy interview, he said he was stunned.

“I got conned,” said the judge. “. . . There’s no question about that.”

Takasugi said he had trusted Uribe. He said they were friends.

“Should I have known?” Takasugi said. “Am I purposely looking the other way?”

Takasugi’s answer was no.

“How do you know when you’re being used?” he asked.

Met in 1960s

Takasugi said he met Uribe in the 1960s. Takasugi was practicing law in East Los Angeles and he represented Uribe at a series of disciplinary hearings held by the state Department of Real Estate, with which Uribe was in trouble.

Uribe had proposed a house swap with a client, taken the client’s house, promptly encumbered it with mortgage loans, then sold his own house to someone else, the real estate commissioner found.

But Takasugi apparently provided an able defense. The commissioner revoked Uribe’s broker’s license but stayed the revocation to give him another chance on the ground that marital difficulties (Uribe has been divorced three times) stood in the way of his completing the transaction honorably.

Within months, however, Uribe had “secretly and fraudulently” sought to buy a half-interest in another house while serving as the broker for the house’s seller and converted funds to his own use that belonged both to his secret co-purchaser in the transaction and to the seller, the commissioner found.

This time the commissioner revoked his license outright.

Takasugi said he had been unable to provide Uribe with an effective defense in that case. He said that Uribe had armed him with information he could have used to establish bias on the part of the key witness against Uribe. But he said that Uribe then refused to allow him to use the information on grounds of chivalry.

Uribe had described the key witness--the seller of the house--as a former teacher of his whose romantic advances he had spurned, Takasugi indicated. Then Uribe said, as the judge reconstructed it: “ ‘I’d rather be disciplined than have to go into something like that against her.’ ”

“Jaye Uribe,” Takasugi said, “as far as I can remember, had problems, whether it dealt with a wife or whether it dealt with his relationship with girls, or his relationship with people in general.”

But the judge said that after Uribe lost his license in 1968, “he went through what I thought was a really impressive redirection in his life, i.e., banking degrees, real estate appraisal degrees and activities of that nature.”

(One of the degrees Uribe claimed was a 1973 MBA from Northwestern University. University officials, however, said they had no record of his having obtained such a degree.)

Accounting at Tax Time “I was really proud of him as a former client,” Takasugi said.

“I mean, today I can look at it and realize that the assessment was certainly stupid. But I was very much impressed with the fact that he went for self-improvement and I sincerely felt that he would be involved in absolutely clear transactions.”

Accordingly, in 1975, while in the midst of a rapid rise through judicial ranks, Takasugi wrote a letter of reference on Uribe’s behalf to the Department of Real Estate to help him get his broker’s license back, department records show.

When the effort succeeded, Uribe’s business relationship with Takasugi apparently took shape.

Takasugi had been named to the municipal bench in 1973, elevated to the Superior Court in 1975 and received a lifetime appointment as a federal judge in 1976.

Takasugi said he had little time for real estate.

“Generally speaking, what would happen,” the judge said, “would be that (Uribe) would call up and say there was a real estate venture, he needed some hard money and, accordingly, I gave him hard money with the responsibility on his part to manage the property, collect the rents, take care of repairs. And I would (get an accounting) at the time of income tax preparation.”

On occasion, the judge said, Uribe would also put up money and they would share in investments.

When a property was sold, the judge said, the two would divide profits.

But Uribe continued to have problems.

Between 1979 and 1983, he was sued a dozen times.

Takasugi said he was unaware of this.

And the judge disputed accounts of two people close to Uribe who said they raised questions with him about Uribe’s conduct.

Uribe’s son, Jaye Mark, said he visited Takasugi in 1981.

The son, then 21, had taken a sledgehammer and smashed the windshields of two of his father’s cars--provoked, he said, because his father had cheated him in some business deals.

The son said he told Takasugi about his problems with his father, and also told the judge that his father was taking advantage of the unsophisticated and the unwary.

He told The Times that his father had “burned so many people it’s unreal.”

Takasugi said he remembered the son’s visit. But he said that the conversation dealt only with the son’s perception that Uribe was “a lousy father.”

Uribe’s former lawyer, James C. Cupp, said in an interview that he too raised a question about Uribe in 1982 with Takasugi.

By then, Cupp no longer represented Uribe and was having his own problems with the broker concerning a foreclosure on Cupp’s house.

But in the course of telling Takasugi about his own troubles, Cupp said, he also mentioned difficulties faced by Uribe’s former employee and childhood friend, Joseph Aguirre, whose Pico Rivera house the judge eventually came to own.

“I said, ‘I think (Uribe’s) screwing Joe,’ ” Cupp recalled. “And (Takasugi) said, ‘No.’ ”

A Lot of Aggravation

Takasugi said no such exchange took place.

“I think that Uribe might have even pulled the wool over Takasugi’s eyes on that Joe Aguirre deal,” Cupp said.

Asked for his own assessment of his former client, Cupp described Uribe as “a real con artist . . . maybe on this side of the law, maybe not.”

But Uribe was apparently not successful financially. By late 1983, he had been kicked out of his office for non-payment of rent and had begun doing business through an answering service.

He frequently filed bankruptcy petitions that had the effect of staving off creditors.

All told, Uribe and his mother--who reported interests that were often indistinguishable--filed for bankruptcy 13 times from 1982 to the present, informing the court falsely in most cases that they had never filed bankruptcy petitions before. And in most cases their petitions were dismissed because of their own failures to follow through on them, court records show.

Takasugi said he had no knowledge of this.

But over the years, he said, he put up with a lot of aggravation from Uribe.

Takasugi said, for example, that he lost much more money than he made in his dealings with Uribe.

He said he almost always had difficulty getting Uribe to return his telephone calls.

He said he often had difficulty getting Uribe to meet deadlines.

He repeatedly had to make payments to mortgage holders, he said, rather than rely on rents to pay mortgage loans, because Uribe had difficulty collecting rents.

He acknowledged that he learned from an attorney in 1981 that Uribe had mishandled one of the judge’s investments.

And he said that he learned from Uribe--at income tax time--that Uribe had repeatedly borrowed money on one of the judge’s properties, a Montebello triplex, then sold it in early 1982, all without Takasugi’s permission.

But, Takasugi said, whenever a problem arose, Uribe had a “satisfactory” explanation.

In the case of the Montebello triplex, for example, Uribe claimed--falsely, Takasugi said--that he had obtained the judge’s permission to sell the property, then justified the sale by telling the judge that he had advanced his own money to make repairs.

Uribe was also “candid enough” to admit that he had needed funds for living expenses, Takasugi recalled.

The judge said he resolved to deduct the money Uribe used for living expenses from the broker’s fees on any future deals.

Takasugi said he thought Uribe might have been irresponsible but not dishonest.

Their business relationship continued. In recent years, the judge said, he referred two of his closest friends to Uribe for deals.

Then came the suit that named Takasugi as a defendant.

Takasugi relied on Uribe, who was named as a co-defendant, to handle it.

No Pretrial Defense

But Uribe failed to mount any pretrial defense and, as a result, he and Takasugi lost the case by default.

“I was flabbergasted,” Takasugi recalled.

Takasugi succeeded in getting the default judgment against him lifted in January, 1984. A judge ruled that Uribe had “essentially abandoned his responsibilities” as Takasugi’s agent and scheduled the suit against Takasugi for a still-pending trial.

At about the same time, a reporter visited Takasugi because of a complaint from one of the judge’s tenants that there was no heat or hot water in a house.

Takasugi said absentee ownership did not work and that he had decided to get out of the business.

During the next eight months, he sold two of the three properties Uribe managed for him.

Uribe was his broker for the sales.

A few months after that, the reporter visited Takasugi again and laid out a number of transactions, details of which Takasugi said he knew nothing.

Takasugi vowed to use another broker for the sale of the last of the properties.

” . . . I know I live in a fishbowl,” he said, “and I like to think I conduct myself in a way where there would be no embarrassment.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.