Bacteria, Chemicals Go Undetected : Meat, Poultry Inspection Insufficient, Report Says

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The federal government’s meat and poultry inspection system--conducted for nearly 80 years primarily by sight, touch and smell--is no longer sufficient to detect modern health dangers such as bacterial contamination or toxic chemical residues, the National Research Council said in a report released Tuesday.

“The American life style has changed, and so have the hazards to human health,” said Robert H. Wasserman of Cornell University’s veterinary college, chairman of the study committee. “Techniques now allow the detection of microbial and chemical contaminants that are not apparent through traditional inspection methods.”

Wasserman added: “The first question on everyone’s mind must be: ‘Is our meat and poultry supply safe to eat?’ The answer is: ‘Yes, for the most part--if it is properly handled.’ ”

New Technologies

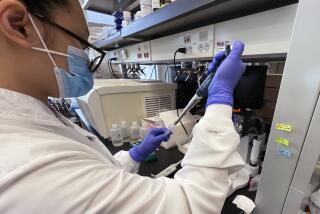

The committee, composed of experts on human and animal health from government, business and academia, urged the adoption of new technologies to spot such health threats as salmonella, a bacteria responsible for about a quarter of food-borne illnesses in recent years, and Campylobacter, an organism similar to salmonella.

In 1983, 44,000 cases of salmonella poisoning were reported in the United States, but thousands of additional cases are believed to go unreported, committee officials said.

The report also said that monitoring “should begin on the farm and in feed lots, where much of the exposure takes place,” instead of in the slaughterhouse, where it now begins.

Livestock and poultry farmers often practice mass production methods involving the routine use of antibiotics, growth hormones and commercial feeds prepared from grains cultivated with chemical fertilizers and pesticides--yet the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Department’s Food Safety and Inspection Service “does not extend that far” back, the report said.

“It’s clear the agency should have more enforcement power than it now has,” said committee member Thomas Grumbly of the Health Effects Institute in Cambridge, Mass. “It should be somewhere between dropping the atomic bomb on someone . . . and slapping them on the wrist.”

The committee recommended the establishment of an identification system through which records could be kept on food animals throughout their lives, enabling the government to trace residue samples back to the source of exposure.

“Right now, the meat inspection system does not look for microbial agents,” said Dr. Morris Potter of the federal Centers for Disease Control, who served on the committee. “The way we know meat is contaminated is after the reporting of human illness.”

The committee suggested that the inspection service employ such technology as ultrasound “for examining animal organs and detecting bone fragments and other materials in meat” and prepackaged testing kits for the rapid identification of residues or diseases in animals before they leave the farm.

Report Is ‘Blueprint’

Dr. Donald L. Houston, administrator of the Agriculture Department’s food safety service, which asked the research council to conduct the study, said: “We have no intention of letting this report gather dust as a ‘historical document.’ Instead, we will use it as a blueprint for future actions.” Some reforms may require legislation.

The current procedures, begun in 1906, “date to a time when acute infections were the leading causes of death” and inspectors were trained to remove diseased animals from the food supply by examining them before and after slaughter for lesions or other signs of disease, the committee said.

But “new information, new technology and new health concerns have severely tested the efficiency and adequacy of the present labor-intensive system,” it said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.