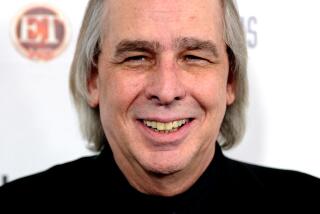

TUNED IN : Collector Philip Collins Finds Beauty in Old, Plastic-Cased Radios

- Share via

Philip Collins (he is not Phil Collins the pop singer--”I have more hair; he has more money”) has collected 200 radio sets dating between 1935 and 1952. One of his friends, mystified by his passion for the gaudy, plastic-cased radios, asked, “Why do you want so many? You can only listen to one at a time.”

It is the variety that attracts Collins. Some of the radios are bullet shaped; others look like miniature, old-fashioned refrigerators. Several are novelty models, in the form of pianos, Coca-Cola bottles, old-style microphones, lamps or giant Barbarossa beer bottles for use in bars.

Collins, who is in the movie business, came to Los Angeles from his native England in 1979. In England, he had collected old jukeboxes. He did not have room for them in his Los Angeles apartment. A friend from New York, actor and writer Larry Pippick, visited him in California and told him that collectors were snapping up old plastic radios at flea markets and swap meets.

So Collins went to the Rose Bowl flea market one rainy morning at 9. “It took me forever to find it; I hadn’t been in town long.” There he found his first radio, an unspectacular, brown Bakelite model made by Philco in about 1948-49. It has a gold-colored, half-moon-shaped dial with an AM band marked 55 to 160. “One of the reasons these radio sets are so accessible,” Collins explains, “is that when FM was introduced in the late 1940s, people discarded their AM sets in favor of AM-FM radios.” So a lot of the plastic sets were abandoned in good condition.

All the same, Collins finds many radios in sorry states. Restoring them is part of the fun. “When I buy them, they’re not cracked so much as dirty. They have 40 years of dust inside, they have knobs missing, the exterior Bakelite is stained. I get a buzz out of rescuing a set that I see in a flea market--broken down, forlorn, pathetic, priced at $5.” Often, the seller does not know whether the radio works. Collins brings it home and switches it on. It lights up feebly, “and I know I’m in business.” Collins admits that some purists might disapprove of the whole-hog way he restores the radio sets. He not only replaces the capacitors and tubes but often paints the plastic sets new colors. He takes the view that he has paid for them and that they are his to do with as he pleases. He has never paid more than $100 for a radio, although models in good condition sell in Melrose Avenue shops for $300 to $400.

Collins muses about why he began collecting old radio sets as opposed to old egg whisks. “I think part of it is my delight with the medium. Radio was a very potent medium that delivered 90% of the entertainment that people had, through those little three-inch speakers. Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds,’ news of World War II. It is interesting to consider some of these designs and to think that out of such beautiful things came the most horrendous news of Hitler’s bombings.”

Most of Collins’ radios are bought before 7 a.m. “That is why most people don’t see them around. The radios have gone by the time the casual browsers reach the markets. The best pieces are almost picked out of the trucks as they drive in.” Today, Collins faces competition not only from enthusiasts for old radios, but from a growing number of people who collect old plastic, whether radios, lamps or tea sets. “There is a very fine line between people who claim to be collectors and people who are in fact dealers,” he says. “Dealers don’t like the term dealers. For some reason they think there’s something vulgar about trade. Almost invariably, you find that people who advertise themselves as collectors are nothing more than dealers. They are only in it for the money. In Oscar Wilde’s phrase, they know the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

Collins does not have a condescending attitude toward trade. As a boy, he helped his father sell candy on the beach in the English seaside resort of Littlehampton. “We worked very hard in summer to maintain life in winter. It was a murderous profession; imagine relying on the sun for your living in England.” He was not, so to speak, switched on by radio sets in England. “Most of them were rather ugly Bakelite edifices that were cumbersome and utilitarian. They were purely functional--and I would say much the same about the radios of today in America. Purely functional. There is nothing aesthetically attractive about a stereo-component set. And this functionalism of home-use durables is leading to an accelerated nostalgia for the 1940s and ‘50s, when those objects did have some qualities beyond function.” He gestures rhetorically at a bullet-shaped 1944 Fada radio, one of his favorites. “Who wouldn’t like to have that sitting on their mantelpiece?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.