Ancient Rock Art Stirs Imagination

- Share via

RIDGECREST, Calif. — Strange and mystifying shapes, immediately capturing the imagination, literally cover the jumbled piles of boulders that form the canyon wall. On one rock a boldly etched stick figure clutches a wooden shaft weighted near one end; nearby a group of sheep tries to outrun a hunter; above, a painted body in feathered headdress glares at me through one large central eye.

It was intriguing, as I gazed about Renegade Canyon, that only a few people know of this place. These petroglyphs, the legacy of an ancient nomadic tribe that roamed the Coso Mountain Range thousands of years ago, constitute the largest concentration of prehistoric rock art in North America.

Just who the people were, why they made these drawings and then vanished, remains veiled in mystery. They disappeared long before the arrival of the Shoshone Indians who inhabited the area during Western exploration.

The drawings occur primarily in two canyons, Petroglyph and Renegade, within the China Lake Naval Weapons Center Firing Range at the northern edge of California’s Mojave Desert. The Navy acquired the area, about the size of Rhode Island, in 1943 for testing weapons and eliminated all public access to the petroglyphs.

In 1964 when the two canyons were dedicated as a National Historic Landmark, visiting restrictions were relaxed, but environmentalists’ constant monitoring of the canyons for “people” damage results in curtailing the number of groups admitted if any serious effect is noted.

Limited Numbers

The Maturango Museum within China Lake is authorized to conduct limited numbers of car caravan tours to Renegade Canyon during fall and spring.

On a Sunday morning, after obtaining clearance at the China Lake check point, I joined the line of gathering cars, vans and trucks in front of the Maturango Museum at 8 a.m. Time is allowed for a look at the museum, which is staffed by volunteers in a Navy-donated building and features Indian artifacts and wildlife from the area.

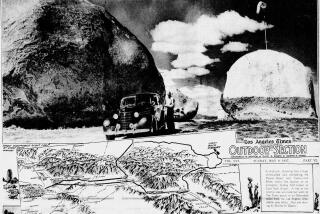

Then, armed with maps and guides for the journey ahead, our 15-car serpentine wound through the base and into the desert for an estimated two-hour drive to Renegade Canyon.

On a surfaced road we crossed the dried bed of prehistoric China Lake, along which you can make out the shoreline. At one point we stopped for a beautiful panoramic view of Indian Wells Valley.

As we began our ascent into the mountains at Mountain Springs Canyon we left behind our paved road for a dirt one. The drive into the Cosos afforded scenic views as well as the opportunity to see a wild burro or horse.

Arriving at the petroglyphs, we took a brief lunch break; then three hours allowed plenty of time to wander through the canyon, scrutinizing the drawings and matching wits with those before who tried to uncover their meaning. On hand to assist was George Silberberg, a physicist employed by the Navy and a weekend petroglyph guide for the museum.

A Wide Expanse

The drawings, divided between Early, Transitional and Late, cover a wide expanse of time. The oldest petroglyphs, possibly dating as far back as 4000 BC, occur at the head of Renegade Canyon and are deeply pecked shapes and small hemispheric pits arranged in lines or at random.

The Early period drawings are rather crude side views of sheep, atlatls (spear throwers) and human-like figures. Migration routes of Indians from South America date the introduction of the atlatl into the Cosos at about 2000 BC.

Showing the change from atlatl to bow and arrow, the Transitional period drawings depict square-shaped, human-like figures and stick men holding atlatls. The bow and arrow makes its appearance in the hands of highly stylized stick men. Frontal views of sheep further indicate an increasing attempt at realism, which dates around 200 BC when the bow and arrow was introduced from Asia.

During the Late period, about AD 300, the bow and arrow fully replaced the atlatl, and drawings show a general trend toward more stylization and better execution. The most dominant style for sheep is “boat-shaped,” with flat back, round belly, thin legs and tiny head.

But the most dramatic drawings of the Late period are the highly ornate human-like figures with feathered headdresses, earrings, painted bodies, fringed skirts and round balls containing concentric circles for heads devoid of features.

The arid Coso Mountains of today, where nothing but hardy desert plants can survive, provide a striking contrast to the lush region of ample vegetation that must have characterized these same mountains 3,000 to 4,000 years ago when great Pleistocene lakes still covered much of Eastern California and many animals, now extinct, roamed the land.

On the basis of material excavated from an early-man site near Little Lake at the western edge of the Coso Range, the people were hunters and seed gatherers. They hunted with the atlatl and later the bow and arrow. Their seeds were ground into flour with manos and metates; they prepared their game with knives and scrapers of obsidian and lived in brush shelters.

Linguistically, the Coso people were early ancestors to the Numic-speaking Shoshone and could be classified as Proto-Numic or Proto-Shoshonean. They took part in a widespread migration that began about 1,000 years ago, largely depopulating southeastern California and southern Nevada, spreading across huge areas of the Western U.S. and settling in regions as far north as Wyoming and east into Texas by the dawn of the historic period.

What caused these tribes to leave their ancestral homes on such a large scale? The appearance of the bow and arrow certainly was an important factor contributing to the migrations. The more sophisticated weapon would have allowed more sheep to be killed, thus upsetting the ecological balance.

Crudely Made

With the atlatl in exclusive use and sheep plentiful, the drawings appear crudely made. As the bow and arrow came into prominence and the number of sheep began to decline, the drawings became more elaborate, accompanied by decorated human-like figures.

Almost without exception, the rock artists made their drawings on migratory game trails, near hunting blinds in narrow gorges or along rock escarpments and in the vicinity of springs where watering animals could be ambushed.

For those interested in joining a car caravan to Renegade Canyon, write to Maturango Museum, P.O. Box 1776, Ridgecrest, Calif. 93555, or call (619) 446-6900. This spring, car caravans will depart at 8 a.m. on April 19, 20, 26, 27; May 17, 18, 31, and June 1, 8, 22.

The caravans frequently fill up a month ahead, making reservations a necessity. A fee of $5 per adult and $3 for children 8 to 15 years old is required to secure the reservation. Museum members are admitted at no charge.

An authoritative book, “Rock Drawings of the Coso Range,” by Campbell Grant, James W. Baird and J. Kenneth Pringle, available through the museum for $10 plus a $1.20 shipping fee, affords excellent background reading for your trip.

The 84-mile round trip provides no gas stations or restaurants, so vehicles going on the trip should be in good repair and have a full tank of gas. You will also want to take plenty of food and water.

China Lake, approached by either U.S. 395 or California 14, is about a three-hour drive from Los Angeles. For those wishing to stay overnight, there are several motels in Ridgecrest. Write to Ridgecrest Chamber of Commerce, Box 771, Ridgecrest, Calif. 92555.

Primitive camping is available at Red Rock Canyon State Recreational Area between Mojave and the 178 turnoff to Ridgecrest. The campground, beneath the spectacular rock formations, has 50 sites open all year that offer table, stove and piped drinking water.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.