Hepatitis Cases Spur Inoculation Gun Probe

- Share via

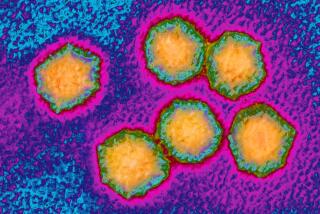

An unusual hepatitis epidemic at a Long Beach weight-loss clinic that began in 1984 has prompted federal health officials to reevaluate the safety of the “jet gun,” a device used widely for mass inoculations in the U.S. military and throughout the Third World.

The jet gun, introduced about a quarter of a century ago, previously had an unblemished safety record.

But now investigators for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control have traced a 64-case outbreak of hepatitis B at a Lindora Medical Clinic to a contaminated jet gun.

“The evidence is incontrovertible that the gun was involved,” said Dr. James Maynard of the Centers for Disease Control’s division of viral diseases. The inoculator was used daily at the Lindora clinic to inject patients with vitamins and a hormone medication.

The jet gun uses pressurized gas to force medications through the skin without the use of a needle and therefore is much more efficient than disposable needles and syringes. An experienced user can inject between 250 and 400 patients an hour.

Health officials are still trying to determine whether the jet gun’s design caused the problem or whether the weight loss clinic is to blame for using or cleaning the gun incorrectly.

“Most likely it was a combination of factors,” said Dr. Jeff Canter, an epidemiologist at the center who investigated the outbreak for the state Department of Health Services.

But Dr. Marshall Stamper, the clinic’s owner, disputed the center’s conclusions. He said the jet gun has been “unfairly blamed” for spreading the virus. But Stamper conceded, “I cannot give an explanation for the cases.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates medical devices, said it does not plan to take any action until its own investigation is completed.

The jet gun, made by Med-E-Jet Corp. of Cleveland, has been “used all over the world” in the last 15 years, according to company president and founder John J. Sibisan. Jet guns were last widely used in the United States during the 1976 swine flu mass immunization program.

“We have never had a single complaint,” Sibisan said in a telephone interview. He declined to comment on the Long Beach epidemic.

Lindora’s outbreak began, health officials believe, when blood from one or more hepatitis carriers contaminated the jet gun. In turn, the jet gun infected other patients. The outbreak “snowballed” as more patients became infected and re-contaminated the gun, Canter said.

Injections by jet gun may cause minor bleeding or bruising even when done properly, he said. If used improperly, the gun can lacerate the skin, causing significant bleeding.

In laboratory experiments designed to simulate normal immunization conditions, Centers for Disease Control scientists showed that if the outside of the jet gun became contaminated with the virus, the inside of the gun did also.

Once contaminated, the jet gun cannot be easily cleaned by the methods recommended between injections, according to Dr. Miriam Alter, chief of hepatitis surveillance at the center.

“If this particular gun is misused or poorly maintained, the potential for transmitting disease is increased,” she said.

It was a Long Beach Health Department epidemiologist who first noticed the unusual cluster of hepatitis cases in May. The clinic, at 3736 Atlantic Ave., stopped using the jet gun on July 2, 1985, a day after the state and federal investigation began.

Subsequently jet guns were removed from the 28 other Lindora medical clinics throughout Southern California. No hepatitis cases have been reported among patients treated at Lindora’s other clinics, including a second one in Long Beach.

During his investigation, Canter said, Stamper and other Lindora officials told him they were unaware of any serious problems with the condition of the jet guns--although an internal memorandum showed that well before the major 1985 outbreak was detected, clinic officials had apparently become quite concerned about improper use of the inoculators.

The March 8, 1985, memorandum, obtained by The Times, warned employees that some jet guns were in “extremely poor condition” and others were “caked” with medicines.

The memo, signed by Nell B. Stamper, Marshall Stamper’s wife and Lindora’s general manager, also said some patients had been lacerated by “poor injection technique.”

Marshall Stamper, in an interview, said he had never seen the memo. “Nobody thought it was important enough to bring to my attention,” he said. Nell Stamper said, “We sent out an exaggerated memo so the nurses would pay a little more attention to what they were doing.”

Records Reviewed

The Centers for Disease Control’s conclusions implicating the jet gun are based on a probe that included a review of medical records, interviews and blood tests of patients who attended the Lindora clinic, particularly in the first six months of 1985. Most patients were receiving jet gun injections at least several times a week.

Over a two-year period ending last November, 31 patients developed hepatitis, a form of liver inflammation, according to Canter.

Another 33 patients developed laboratory evidence of infection without actually becoming sick. Exposure to the jet gun was documented in all patients who developed hepatitis, Canter said.

Hepatitis patients usually recover in 6 to 12 weeks, even without therapy, although a small percentage develop chronic liver disease or become virus carriers.

Detailed Study Made

A key aspect of the center’s investigation was a detailed review of how the jet gun is actually used. According to Lindora’s written procedures, the patient’s skin is first cleaned with acetone. Then the jet gun is pushed firmly against the skin and the medicine is injected. The head of the gun is wiped with a cotton ball moistened with alcohol before each injection.

Lindora nurses were instructed to periodically wash out the jet gun with alcohol during the day. And at day’s end, the jet gun was to be cleaned, scrubbed and soaked in alcohol.

“The clinic’s written procedures for using the gun appeared adequate, but we couldn’t reconstruct how all the the shots were actually given,” Canter said.

In an additional laboratory experiment, center researchers were unable to contaminate the jet gun by a series of five injections into a chimpanzee who had chronic hepatitis B infection.

The center’s Maynard acknowledged that this experiment may not have been sufficient to prove that the jet gun “could not be easily contaminated” during actual use.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.