Scout Who Discovered Saberhagen Convinced the Royals With Radar

- Share via

Radar guns are as common in the bleachers at high school baseball games as they are in highway patrol cars.

Guy Hansen, a professional baseball scout with the Kansas City Royals, has firsthand knowledge of both.

A few years ago, while driving back to Los Angeles from the Arizona Instructional League, Hansen was cruising along at 65 m.p.h., 10 m.p.h. over the limit, when he was pulled over by an highway patrolman.

After unsuccessfully pleading his innocence, Hansen tried to prove that the officer had erred, challenging him to a round of dueling radar guns.

The two men stood on the shoulder of the road and trained their guns at passing cars. The instruments gave different readings.

“He told me to just forget it,” Hansen said. “Then he told me to get the hell out of Arizona.”

That type of gambler’s bravado has become Hansen’s scouting trademark.

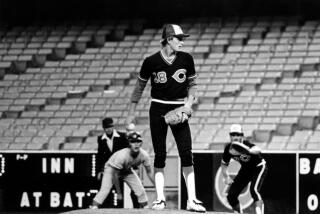

It was in evidence when he convinced the Royals to sign a skinny kid from Reseda named Bret Saberhagen.

“A lot of baseball people had written Saberhagen off as a top prospect and that explains why even we didn’t draft him in the first few rounds,” said Dick Balderson, the Royals’ former director of minor league development. “But Guy stuck with Saberhagen because he thought that Bret had the ability to be a major league player even if arm problems prevented him from pitching. It was, obviously, a very good piece of scouting.”

Hansen, 38, has worked as a scout for the Major League Scouting Bureau, the Royals and the Milwaukee Brewers.

A former pitcher at Taft High and UCLA, Hansen still holds several records for the Bruins. He once struck out 11 consecutive batters against Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. He was a teammate of future major leaguers Chris Chambliss and Bill Bonham on the only UCLA team to reach the College World Series in Omaha, Neb., in 1969.

That same year, Hansen was drafted by the Royals. He played four years in the minor leagues and got as far as Double-A Jacksonville before quitting to pursue a career as a professional golfer.

Hansen was a one-handicap golfer but returned to baseball to become a scout. He first saw Saberhagen pitch as a 15-year-old in American Legion ball.

“He had real long hair and he was playing the outfield,” said Hansen, who is the pitching coach for the Royals’ Class-A affiliate in Eugene, Ore. “He came in and pitched a couple of innings and I marked him down as a definite follow. He already had a fastball, changeup and a ‘nickel’ curve. He knew what he was doing out there.”

Every scout had Saberhagen tabbed as a player to watch when he was a junior at Cleveland High. But before his senior season, he hurt his shoulder. The fluid delivery that impressed the scouts was gone. The scouts lost interest.

Enter Hansen and his radar gun.

Saberhagen was pitching against El Camino Real in his senior year, and Hansen happened to be in the stands. For the first two innings Saberhagen was “pushing” the ball up to the plate.

“In the fourth inning, he got his arm back up on top of the ball and started bringing it,” said Hansen, who dispatched a young boy to retrieve the radar gun from his car and posted both the boy and the gun behind a fence where no one could see them.

“Saberhagen was throwing between 85 and 88 m.p.h.,” Hansen said. “I didn’t go back and see him the rest of the year because I didn’t want anyone to know how interested I was.”

Hansen pushed hard for Saberhagen’s selection with Balderson, who is now vice president of baseball operations for the Seattle Mariners.

The Royals drafted Saberhagen in the 19th round of the 1982 June free agent draft. A few days days later--four years ago today--Saberhagen pitched a no-hitter in the City championship game against Palisades. The rest--the 1985 American League Cy Young award, the 1985 World Series Most Valuable Player award and a $925,000 salary won through arbitration--is history.

Other major league organizations would do well to learn from the Saberhagen saga, according to Hansen.

“The story with Bret is so logical,” Hansen said. “After he was drafted, he went off to Hawaii and relaxed with a friend. He didn’t have to go to rookie ball and fight through his shoulder problems.

“He went to the Instructional League where he was monitored by coaches, played with good infielders and pitched in big, spacious parks under almost ideal conditions.

“Add to that his instincts and you see the results,” Hansen said. “I think a lot of baseball people should recognize the road he traveled and apply it to other kids.”

Hansen will scout the Instructional League next fall and then resume his scouting duties in the Valley, following his coaching stint this summer. He believes there is no science to finding future major leaguers; no radar system to nab every prospect that comes along.

“You have to be a little bit crazy to be a scout,” Hansen said. “If you don’t have a little imagination, you’re in the wrong business.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.