‘The people who call me have developed a sense of trust.’ : Talkradio Psychiatrist Quick to Unmask a Lie

- Share via

If Dr. David Viscott had gone into police work instead of psychiatry, he’d have been the big guy gnawing on the toothpick, tapping his foot, sweating the crook under the spotlight. The quick confession expert.

The real Viscott is not big, nor does he chew toothpicks or deal with nasty forms of coercion. But KABC Talkradio’s syndicated on-the-air psychiatrist does deal with confessions, dozens of them each week, and he can usually extract even the most convoluted ones in about the time it takes to boil an egg.

From 2 to 4 p.m. Wednesday through Friday, he will refuse to let a caller ramble, or evade a question, or speak at any time what Viscott determines to be nonsense or lies. On one recent program, for example, he determined that one caller’s extreme nervousness was caused by a longstanding feeling of grief over the death of his father, that a teen-ager’s anxiety about being left alone had its roots in lack of comprehension of the death of her grandparents and that a middle-age man’s feelings of worthlessness were groundless--each conclusion reached and warmly but simply communicated in five minutes or less.

It is no-frills psychiatry. But the approach works so well, Viscott claims, that he has made it the basis of his entire method of analysis.

The Viscott Method, as he calls it, basically involves three elements: simplicity, speed and a relentless pursuit of the truth, all of which he used as touchstones in his explanations before and during a lecture on the topic of personal freedom last Saturday at Rancho Santiago College in Santa Ana. Freedom, he told his audience, means finding one’s true self through belief in oneself, willingness to confront the truth and ability to “come from love”--base one’s actions on love for self and others.

“Rancho Santiago College has had a long history of presenting lectures by personalities from KABC, and the lectures have always been well attended,” said Jane Eimers, who is in charge of program development in the college’s community services office. “Also, we know Dr. Viscott has a large audience in the Orange County area.”

(Jamie Maskell, KABC’s market research director, estimated that Viscott’s weekly audience in Orange County was slightly more than 104,000--about a third of the total figure for the Los Angeles metropolitan area.)

Members of Saturday’s audience were lined up outside the gym door nearly an hour before Viscott’s talk and, once inside, filled the gym floor and most of the bleachers on either side of the room. Strictly attentive but not boisterous (Viscott is not a cheerleader) audience members appeared relaxed during Viscott’s talk and unhesitatingly offered answers, both individual and collective, when he posed questions such as, “How many of you can say exactly what you mean to the person who needs to hear it most?”

The lecture was sponsored by Fullerton, Rancho Santiago and Irvine Valley community colleges.

Speaking in the campus gymnasium to nearly 1,000 people, Viscott frequently returned to the theme of stripping away “lies we tell ourselves” in the attempt to find the truth about the way we behave. It is a psychoanalytic technique, he said earlier, that he uses in rapid-fire fashion on the air.

“I try to present as clearly as possible in the time I have the one piece of advice I need to give to that person,” he said. “I don’t just sit there and listen. I’ll say: ‘Why do you feel so sad? What’s going on here?’ In a situation like that, if a psychiatrist just sat back eating India nuts, he wouldn’t make it.”

Viscott, 48, a native of Boston, who now lives in the Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles with his wife and four children, received his MD from Tufts Medical School in 1963. He became a resident in psychiatry at Boston University Hospital in 1964 and was an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA from 1980 to 1982.

Viscott is part psychiatrist, part entertainer, part philosopher, part entrepreneur--an eclectic jumble that has been the source of a prodigious output of work, including 12 books, several lines of greeting cards, self-help video and audio cassettes, magazine articles and columns, an analytical game called Sensitivity and the Viscott Institute, a Sherman Oaks outpatient psychiatric center.

And upcoming, a self-produced magazine, titled Feelings, that will deal with human emotions and attitudes, is scheduled to begin publication and nationwide distribution next year. And, he said, a nationally syndicated television program produced with Dick Clark Productions, “In Touch With Dr. David Viscott,” probably will go on the air in the fall of 1987. The show will be a kind of extension of his radio program, Viscott said, bringing together several people with similar problems at one time.

Each enterprise, he said, is a fresh manifestation of his zeal to help people find their own true and best selves.

“I’m awake and I want everyone else to be awake,” he said. “On an average day I’ll have at least three or four ideas about different projects or different ways to do things. I feel very dedicated to my profession, but I try to keep my ego out of it.”

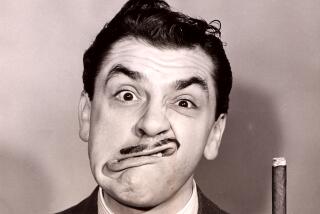

He speaks with the passion of a crusader and the timing of a stand-up comic, looking not unlike a charged-up teddy bear in a summer suit, gesturing broadly, frequently asking for en masse answers from the crowded room.

‘Confrontive’ Therapy

It is an extension of his on-air persona, which he calls, among other things, “confrontive.” Callers--he has an estimated million listeners a day in more than 60 cities--may deny they know why they feel unlovable, or unmotivated, or fearful, but the denial lasts only as long as it takes Viscott to cut in and cut through the caller’s defenses. His tone is familiar, not clinical. He will frequently ask, simply, “So . . . what’s going on?” or refer to a caller as “my friend.” He probes, often in an urgent voice, and is not reticent about telling callers that they are talking nonsense when they hedge a question.

“I’m a catalyst,” he said. “The therapy I do on the air is as genuine as going to a psychiatrist. The program has served as a model for confrontive therapy.”

In 1984, he institutionalized that model in the Viscott Institute, which offers a kind of turnstile psychotherapy that Viscott says is unique in his profession.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the institute’s therapy program is its brevity. Patients are seen for a maximum of four sessions, each session lasting two hours and costing $350. Sessions are recorded on an audio cassette, and the cassette is given to the patient to review at home. There is no time spent in review of a previous session.

“They’re being confronted heavily with very heavy stuff,” Viscott said. “With the tapes, you can sit down and listen to all the lies you told the therapist and recognize them and correct them. You can lie to the therapist, but when you listen to the tape, you can’t avoid the truth.”

The nearly 2,500 patients who were treated by psychiatrists at the institute during its first year of operation enjoyed a high rate of success, according to Viscott, who called his method “ bedrock psychiatry.” At its simplest, Viscott’s method classifies patients as having one of three types of defense mechanisms: denial, excuses or pretense. It then determines whether they are experiencing pain from their past (anger), pain in the present (hurt) or pain concerning the future (anxiety).

“And that’s it,” said Viscott. “Bang. Next question. That’s what therapy is all about. Therapy is about work, and the therapist is the employee of the patient.”

Such an approach is not a usual one in the psychiatric profession, where, said Viscott, many therapists tend to be slower and more passive.

‘Not Disciplined’

“They’re fascinating people to be with,” he said, “but they can be incomprehensible even to themselves. They’re a laughingstock because they’re not disciplined. Psychiatrists tend to play certain roles, and the profession avoids confrontation with itself. I love my colleagues, but I find myself so far away from them.”

Viscott’s more simplistic approach to psychotherapy did not reveal itself overnight but actually grew out of years of writings and other projects that appear anything but simple when listed on paper.

Among his books is the bestselling “The Making of a Psychiatrist,” published in 1973, in which Viscott said he tried to “demystify” his profession and humanize the figure of the psychiatrist. In 1969, he developed Sensitivity, a game in which adults are assigned hypothetical life problems to act out and solve. He has produced several lines of popular greeting cards--among them Sensitivity, Intimate Afterthoughts and In Touch--designed to help people communicate intimate or personal thoughts which they may have difficulty verbalizing. The In Touch line is distributed in 30,000 stores in the United States and Canada and is being translated into foreign languages, Viscott said.

The cards, he said, help people to “walk before they can run,” expressing such hard-to-say thoughts as “If I can’t say no, I can’t say yes . . . and I want to say yes.”

Avoids Burnout

Currently, however, Viscott is known primarily through his radio show. (He began the show on Saturday nights in 1980, eventually taking over the three-day-a-week slot last November from Dr. Toni Grant, KABC’s former on-air therapist.) He has admitted to the audience that listening to his callers’ woes one after the other can be trying. However, he said, his incisive method of questioning and quick solutions have helped him avoid burnout both on the show and in private practice by preventing him from dwelling on patients’ problems and becoming absorbed by them. Rather than dwelling on problems, he steamrolls them.

“My listeners have developed a long-term relationship with me,” he said. “And the people who call me have developed a sense of trust. They don’t see me as a psychiatrist but as a wise friend. I don’t think I’m saying, ‘Look how bright I am,’ but I think I succeed because I get right into it. I’m not afraid. (But) I’m not a maverick. I’m a child of the new age, and I think this is the age of feelings. And I still have 50 years of good energy to give away.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.