Anagrams by Lorrie Moore (Knopf: $15.95; 204 pp.)

- Share via

An anagram, for those who’ve forgotten or never knew, is a word or phrase made by rearranging its letters, as now , won or dame , made . In the plural, as in the title of Lorrie Moore’s first novel, the word means a game of making words by rearranging or adding letters. A baby, announces Benna Carpenter, heroine of the novel, is “not much more than a reconstituted ham and cheese sandwich. Just a little anagram of you and what you’ve been eating for nine months.” And a first novel, Benna might say, is a little anagram of the writer’s talent and what the writer hopes will work.

In her first novel, Moore ventures an anagrammatic experiment in storytelling. She takes four characters--Benna Carpenter; Gerard Maines, the love interest in various guises; Benna’s perfect, wise daughter Georgianne Michelle, and Benna’s wisecracking best friend, Eleanor--and changes their relation and circumstance in each chapter. Benna teaches aerobics to senior citizens, teaches creative writing at a community college, and is a nightclub singer in the Midwestern town of Fitchville, where the novel is set. Gerard teaches aerobics to pre-schoolers, sings in local nightclubs, is devoted, distant, a friend, a successful lover and a failed one.

Moore makes her novel even more of a game by letting us know early on that Eleanor and Georgianne are not real--as the fictional Benna and Gerard are--but are imagined by Benna. (Benna and Gerard sometimes indulge in such cute dialogue that one concludes that the difference between imaginary fictional characters and plain old fictional characters is that the imaginary ones get the better lines, at least in Eleanor’s case.)

This device, perhaps meant to show levels of imagination and perception, best serves the slow revelation of Benna’s childhood in Upstate New York and her relationship with her parents. But it is hard to care for the real imaginary and fictional imaginary characters when the writing makes little distinction between them.

Because of its form, the novel is episodic, often seeming like a series of one-liners or illustrations of contemporary middle-class social problems, a kind of novelized “Hers” column. I missed the sense of a continuing, dramatic present.

What Benna wants (at least in one incarnation) is a traditional family life. She says of her senior-citizen students, “They had, finally, the only thing anyone really wants in life: someone to hold your hand when you die.” But she seems thwarted in her desire by something that the novel never quite communicates. Is it her wit? A fear of intimacy? She has a lover whom she can’t accept because, as he puts it, he wants to be an orthodontist, and she wants him to be a tragic Vietnam vet.

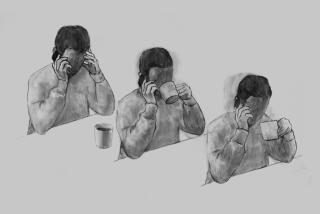

Perhaps the puns and anagrams are to blame for Benna’s loneliness and sadness. Nothing is accepted for itself. Every small piece of action sparks another game rather than a direct reaction. Benna as a teacher demands passion from her students, demands that their work look like pictures of their souls that she asks them to draw at the beginning of the term. I wonder what she’d think of this novel. If “Anagrams” is about writing, about the slipperiness of imagination, then the form might have been pushed further, to make this clearer to the reader.

There are passages in “Anagrams” where Moore shows feeling for language and for her characters all at once, and it is on such passages that I base my hope for Moore’s future work. She is best known for her book of short stories, “Self-Help,” and her first novel shows an appetite for the difficulties of the novel form that should serve her and her readers well.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.