Collector of Drums : This Retired Dentist Doesn’t Miss a Beat

- Share via

His patients always knew that Dr. Joseph Howard marched to the beat of a different drummer--dozens, in fact.

Howard, a retired dentist, acquired his passion for drums as a boy when he spent three years in British Guyana. For the last three decades he’s made it a point to take every vacation in some enchanted far-off land in order to collect drums, rattles or other folk instruments.

Beloved Trophies

Slowly, the walls and shelves of his large two-story home in Central Los Angeles’ fashionable Lafayette Square filled with 600 of his beloved trophies. They include a donkey’s jaw from Cuba, in which the loose teeth create a rattling sound, an Egyptian drum made from flounder skin stretched across a clay bowl, and a Jamaican rattle that is a really a dried 18-inch bean.

Howard retired from his practice in 1981, but still works hard at collecting. Now 74, he will show 25 of his prized possessions at the Day of the Drum Festival at the Watts Towers on Saturday and next Sunday--two of only four public viewing days at the Towers this year.

The famed landmark at 1765 E. 107th St.--an assemblage of scrap steel, mortar, bits of tile and bottles soaring more than 100 feet--will be open from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. both days while drummers play on nearby stages and vendors sell foods and crafts.

Under Renovation

Fashioned over 33 years by Sam Rodia, an unlettered Italian immigrant, and acclaimed throughout the world as an artistic masterpiece, the structures have been under renovation since 1978 and available for group tours, but only occasionally for individual viewing.

This year, in addition to the Day of the Drum Festival, the Towers were open to the public two days during a festival in July.

Members of the Young People of Watts help provide security on festival days, and Capt. Stephen Gates of the LAPD’s Southeast Division said that since the festivals began 10 years ago, no major incidents have taken place at these public events.

Howard became fascinated with drums as he studied them and realized that, since antiquity, man has been moved by their rhythms.

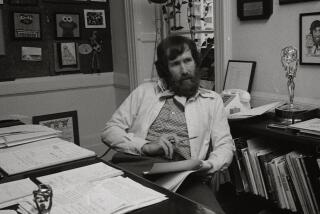

On a hot day recently, dressed casually in a sport shirt and lightweight slacks, he pointed to a bag of flutes hanging on his den wall. “The flute is probably the second most common instrument in the world,” Howard remarked. “The only place you can’t play a flute is a cold area because you can’t pucker.

“But you do find a drum. I haven’t found any culture that does not have a drum.”

Most of his instruments hang in a den and in a detached recreation room behind the home he shares with his son, Brock, 32, and daughter, Viki, 31, as well as a large, black Great Dane called J. C. His wife of 32 years, Bootsie, died in 1985.

Oriental, European, American and African drums fill each of the den walls. Howard keeps track of this hodgepodge from a small room beside the den crammed with shelves of phonograph records, books about drums and a file index of each of his 600 items.

He got interested in drums at age 6 when his mother died and he went to live with his grandmother in what is now Guyana. Young people there beat rhythms on large fruit cans. “The back of our house faced the beach and everybody used to come down and play,” he recalled.

When his father remarried three years later, Howard moved back to Chicago. He remembers friends using the wooden steps in front of his home as drums.

“We would (also) use wooden boxes or large tomato cans,” he said. “I’d go to the ice cream parlors and play the counter. We’d hum the rhythm to complete the sound of the drum.”

Moved Practice Here

After his graduation from dental school at the University of Illinois, Howard moved his practice here in 1952.

As Latin music became popular, he began the first of five years of drum lessons. “I was trying to improve my repertoire of (rhythm) patterns and I began to look at ethnic patterns,” he said. “Then I began to collect.”

Howard found most of his collection through stamps, which highlight the instruments of the issuing countries. “There is no better source,” he said. A stamp house sends him any new postage relating to folk instruments and he files them by country in a loose-leaf notebook.

This December he hopes to find more rare folk instruments in New Guinea, Australia and Fiji. On his drum hunts, Howard often gets help from local ethnomusicologists, writing ahead or contacting them on his ham radio to ask their aid.

“I’ve gone places and when I arrived, they’ve had it (waiting) for me,” he said, snapping his fingers to show how fast it was done. “It’s their hobby. You show an interest and they’re glad to help.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.