Working Well With Congress Should Top Reagan’s List

- Share via

Beyond the obvious lessons of the Tower Commission report, this is also an appropriate time to remember that our system of government works best when it has a strong, effective presidency. A strong presidency requires an effective National Security Council and staff and a recognition that the making of foreign policy is a shared constitutional responsibility between the White House and Congress.

The Tower report has been a major blow to the Reagan presidency. And ongoing investigations may well be even more damaging.

However, our system almost demands vigorous White House leadership in the policy process: We need Hamiltonian energy in the executive to make our many-splendored yet many-splintered Madisonian system of government achieve those long-cherished Jeffersonian ends of liberty and freedom.

Reformers will likely be pushing countless remedial recommendations that might have the effect of weakening the institutional presidency. We need to keep in mind, however, that it is not easy to contrive devices that would check a President or White House staff who would misuse their powers without hamstringing future Presidents and staffs who would use the same powers for democratically acceptable ends.

We need also to remind ourselves that a strong National Security Council and staff are essential to an effective Chief Executive. In many respects the incumbent President was hurt by an NSC system that was too weak, not too strong. It suffered from too much turnover (five advisers in six years). It suffered from too little stature at the White House staff level. It suffered from too few meetings of the official Cabinet-level National Security Council itself. And it suffered from too little sustained debate and discussion by the President and the Cabinet-level members.

Obviously the main fault lies with President Reagan, who lacked the curiosity and the interest in having the national-security system operate as the serious multiple-advocacy advisory system that it was intended to be.

Yet a strong presidency also is one that recognizes its limits and realizes that it is merely a co-equal branch, especially in the setting of national public policy.

Too many of the aides and advisers in this Administration, perhaps with an unbecoming hubris arising out of the 1984 presidential reelection landslide, grew impatient with Congress. As one senior Reagan Administration official put it to me this past month, “The framers did not expect the Congress to play a co-equal role in the making of foreign policy.”

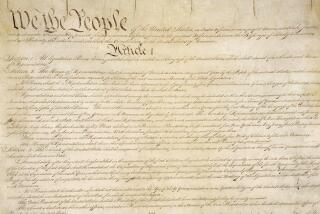

Wrong! Congress was given, quite specifically, the power to approve treaties, the confirmation authority, the lawmaking power and also the appropriation powers. To be sure, these powers were to be shared with the executive--but they were indeed intended to be shared. The framers realized, of course, that the day-to-day conduct of negotiating treaties or the day-to-day conduct of an ongoing war would be assigned primarily to the executive--but there are no provisions in the Constitution of the United States, nor were any intended originally, to allow a President and his aides the right to make policy as an ongoing proposition and to conduct extensive undeclared foreign policy.

Congress, for its part, may also have been lax in performing its responsibilities. Perhaps the time has come for Congress to reorganize itself in a way that will enable it to better collaborate and consult with Presidents, and vice versa. Perhaps, for example, there could be established a National Security Leadership Committee, made up of the ranking party leaders in both chambers and the chairpersons and ranking minority members of the foreign-relations, armed-services and intelligence committees--a group that could regularly be briefed by the President and the secretary of state and that in turn could regularly ask tough questions directly of these senior foreign-policy leaders of the executive branch.

Members of Congress do not represent the American people exactly as the President does, but the two houses collectively represent the people in ways in which a President cannot and does not. In the end the issue in this affair, as it was in the Watergate affair, is not whether the presidency should be stronger than Congress, or vice versa. The challenge here is that Congress and the presidency as institutions must both be strengthened to do the pressing collaborative work required for the well being of a constitutional republic.

The Tower Commission treated the Administration more gently, in all likelihood, than history will. Americans and the historians are generally harsh critics of past Presidents who left the office weakened and who violated the spirit of constitutionalism. Reagan still has time left to repair some of the damage. But if he is to have a strong presidency, it must be one with a strong staff system and one that recognizes the co-equal status of Congress as a policy-making branch.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.