Despite Modernization, Home Weavers Still Backbone of Donegal Tweed Industry

- Share via

DONEGAL, Ireland — Irish crofters used to weave Donegal tweed on hand looms in their cottages and then bring the distinctive cloth to market on the family donkey.

Today they still weave the cloth on the same looms--which have been passed down from generation to generation--in this remote and ruggedly beautiful corner of northwest Ireland.

But now it is collected by van from the whitewashed cottages and taken to a Donegal factory, where designs from the fashion houses of Paris and New York are plotted by computer and the tweed cutouts are printed by laser pens.

To many fashion-conscious shoppers around the world, Donegal means tweed, and much of the credit for that immediate word association must go the weavers.

Part-Time Weavers

They are hill farmers who have to find time to weave the tweed in between feedings cows, cutting turf for peat fires and tilling small vegetable plots.

Nowadays their talents are part of a highly organized chain, which starts with their being given high-quality yarns to weave at home.

They then go through the factory process, being meticulously checked for quality and washed, scoured and pre-shrunk in the gentle peaty waters of the River Eske, which runs through the town of Donegal.

Magee, the largest tweed maker in Donegal, employs about 50 outside weavers among its 600 workers. Still, the industry is at the mercy of ever-changing fashion tastes.

“Cyclical” Business

Lynn Temple, managing director of the company, which has annual sales of about $22 million, said the business is “very cyclical.”

“Everything in the garden is rosy when people want chunky tweeds,” he said. “One of our strengths is the diversity of our markets.

“The United States is very difficult at the moment. Japan and Italy were particularly good last year.”

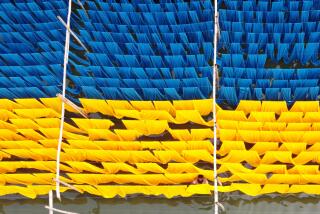

Asked what makes Donegal Tweed so distinctive, Temple looked disparagingly at a reporter’s jacket and said: “That’s obviously Italian. The colors are much flatter. Italians make Donegal-type cloth, but they do not have the richness of color we get in Donegal.”

Matter of Survival

“The reason it (the business) began in Donegal was that people had to survive on poor land and needed to augment their income,” Temple said. “This is an unusually intelligent population with a natural aptitude.”

About 500 visitors a week tour the Donegal factory in summer to see everything from the old wooden looms, practically unchanged since biblical times, to the modern, power-driven ones.

Old intermingles with new, such as a computerized system that plots out exact pattern sizes for the cloth, cutting wastage down to practically nothing.

“As a product, it (Donegal tweed) has developed with the technology of the time while retaining its hand-woven aspect,” said Peter Sweeney, a Magee director who takes visitors around the factory with obvious pride.

‘Appealing Life Style’

Of the firm’s outside weavers, he said: “It’s obviously a life style that appeals to them. It’s the ultimate in flexitime for the hours of work.

“They can be saving hay or turf when it’s a good day. And when it’s raining, they can come inside to do the weaving.”

But the weavers still must be disciplined links in the chain because, Sweeney said: “This cottage industry is set up on a tight production schedule. The romantic story is fine, but the customer in Tokyo or New York still needs his cloth on time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.