Telstar Turns 25: It’s a Small World After All : Satellites Have Become Town Criers for the Global Village

- Share via

EAST MONTPELIER, Vt. — A mile from the nearest paved road, James Murphy sits in his mobile home and steers a 10-foot-wide satellite dish that stands out by a stone wall.

Up pops Ronald Reagan, translated into Spanish. Boston Bruins trivia. Shop-at-home socket wrenches for $19.95. News in Italian. The First Baptist Church choir of Del City, Okla.

Satellites have been beaming a crazy-quilt world into the snug Vermont living room of Murphy and his wife Alice for nearly three months, ever since they bought their dish in April for a little more than $3,000.

“The kids were after me,” said Murphy, a 76-year-old retired crane and shovel operator. “They said, ‘Why don’t you get a dish so you can enjoy yourself?’ And we really have.”

The world has become a smaller place for Murphy and everybody else in the quarter century since communication satellites began circling the Earth as the relay towers of the Space Age.

Before satellites, continents were linked only by clumps of copper cables. Film footage had to be sent across oceans by plane. Long-distance phone calls were considered special occasions in most homes.

Telstar the Granddaddy

This Friday marks the 25th anniversary of an event that changed all that: the 1962 launch of Telstar I. The experimental “bird” was the first to receive, amplify and simultaneously retransmit telephone and television signals and thus was a forerunner of the modern communication satellite.

Telstar’s first transmission, a phone call to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, “ranked with such historic accomplishments as the first transmission of a telegraph message by Samuel F. B. Morse in 1844,” bragged its owner, Bell Telephone Laboratories.

Today, communication satellites are fixtures in the firmament. Link Resources Corp., a market researcher, predicts that satellite services in the United States alone will generate $3.75 billion in revenue by 1991, growing about 15% a year.

Satellite owners are reaching out to new customers. Coca-Cola Co., for example, used satellites to beam a two-hour presentation to 15,000 bottlers in Australia, Africa, Japan, Brazil and Great Britain. Johnson & Johnson used video conferences to get information out quickly during its Tylenol scare.

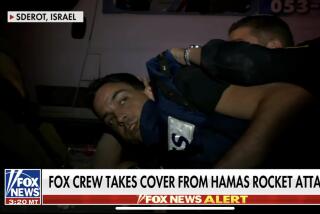

The latest innovations include tiny dishes that news organizations can assemble like petals of a flower to broadcast live from remote war zones and disaster areas.

On the other hand, satellites hover above a dangerous landscape, filled with competitive threats and political squabbles. Among them:

Competing technologies, such as optical fibers that cheaply transmit pulses of laser light, are bringing some voice and data traffic back to Earth.

Several rockets have blown up or gone astray with $100-million satellites aboard, bringing most launches to a temporary standstill and driving insurance rates into the stratosphere. More than two dozen satellites had been on the waiting list for the space shuttle before the explosion of the Challenger in 1986.

Hackers like the infamous “Captain Midnight,” who interrupted Home Box Office Inc. last year, have highlighted the vulnerability of satellites to sabotage.

The French, Soviets and even Chinese are trying to muscle in on the satellite-launching business with government subsidies. Japan, too, is reaching into space. Next February, Mitsubishi is scheduled to put up the first communications satellite designed, built and launched entirely by Japan.

Third World nations that depend heavily on satellites are opposing efforts by the United States to allow the launching of private international communication satellites, which they fear would skim off profitable traffic and force up their transmission rates.

The actual Telstar I was a short-lived phenomenon, succumbing to radiation just seven months after its launch. Now deaf and dumb, it continues to zip around the globe in a lopsided orbit every 2 hours, 40 minutes, passing within 600 miles of Earth at its nearest point.

Telstar’s roughly 120 descendants, in contrast, are crowded into a lofty band 22,300-miles high, an orbit that keeps them in lock step with the rotating surface of the Earth so that they appear to remain stationary overhead.

A single modern communication satellite can carry as many as 30,000 telephone calls and three television channels at once.

The historic effect of Telstar can be measured in a monthly phone bill. In 1963, when AT&T; began offering service to American Samoa in the South Pacific, the calls went through a radio operator in Oakland--when one was available--and cost $33 for 10 minutes.

Today, a 10-minute call to Pago Pago can be dialed directly and costs just under $17. Other consumer prices have nearly quadrupled in the same quarter century.

Telstar’s influence can also be seen on the nightly news. During the Vietnam War, when filmed scenes of jungle combat and dead bodies began making their way to American living rooms, satellites were still primitive.

The nearest dishes to Saigon were in Hong Kong, Thailand and the Philippines. They had to be booked in advance, and they cost about $3,000 for the first 10 minutes, remembers David Buxbaum, director of special events for CBS News.

“It had to be a pretty major story in the early days” to justify a satellite, Buxbaum said. The normal procedure was to put the film on the next commercial flight back to the United States.

A few years ago, CBS News began using a collapsible dish that fits in a few packing crates and allows correspondents to report live to anchors in New York from nearly anywhere in the world. Its first use was covering the downfall of Ferdinand E. Marcos in the Philippines.

Other networks that had been lugging satellite dish trucks around on giant cargo planes quickly followed suit. The results are evident almost every evening now on television, when reporters in odd locales converse with anchors in New York.

Extravaganzas such as Live Aid, the international concert for African famine relief, are another outcome of advances in satellites.

“I know the warmth these cold birds can bring. These are man-made meteorites made out of metal and silicon, but I tell them what to do,” said Tony Verna, president of Global Media Ltd. in Marina del Rey, the maestro who produced Live Aid and Pope John Paul II’s June prayer for world peace.

There is spectacle and then there is business, where money-making opportunities still abound. For example, satellites have made possible such budding “fourth networks” as Rupert Murdoch’s Fox Broadcasting Co., Ted Turner’s Turner Broadcasting System, Home Box Office Inc. and Showtime/The Movie Channel Inc.

One hot area is VSATs, for very small aperture terminals, which are dishes just a few feet across that have come down in price and are being used by companies mainly to transmit streams of data.

There is even some profit potential in the troubled launch business. General Dynamics Corp. announced in June that it would build 18 Atlas-Centaur rockets during the next five years to launch communication satellites. The firm is joining McDonnell Douglas Corp. and Martin Marietta Corp. in trying to fill the void in launchers left by the Challenger explosion.

The U.S. rocket builders are competing for the business of both foreign and U.S. satellite companies--such as AT&T; Communications; Communications Satellite Corp.; GTE Spacenet Corp.; Hughes Aircraft Co.; Western Union Corp., and RCA American Communications Inc.

Still, the greatest fascination of Telstar and its progeny remains their human touch. Although vulnerable to the sabotage of clever hobbyists like “Captain Midnight,” communication satellites have obliterated the old boundaries that once limited the reach of the everyday phone call or the selection of shows available for an evening in front of the television set.

In Vermont, Jim Murphy discovers that the Boston Bruins scored 14 goals against the New York Rangers on Jan. 21, 1945. On another channel, the Salt Lake City, Utah, fire chief is discussing abnormal snow melt in Colorado’s Wasatch Mountains.

“We’ll turn it to something and if we like it, we’ll watch it,” Murphy said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.