THE 1987 PAN AMERICAN GAMES : U.S Pitcher Dazzles ‘Em in a Lot of Different Ways : Abbott Prefers Good Arm Is Seen

- Share via

INDIANAPOLIS — The U.S. baseball players were going through calisthenics before a game last week, when an assistant coach, Brad Kelley, ordered them to touch their toes.

“You too, Abbott,” Kelley said.

Then he grinned.

So did Jim Abbott.

“There are some other things I can’t do,” Abbott said later. “Like my left cuff link. That’s a tough one.”

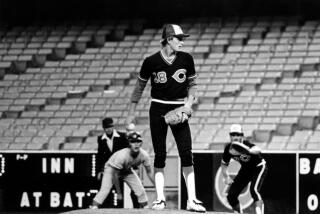

Just as the fact that Abbott, 19, was born without fingers on his right hand has not inhibited his sense of humor, neither has it been a handicap to his ability as a pitcher. The University of Michigan sophomore has been the United States’ most effective starter in the Pan American Games, allowing four hits and striking out six in five innings of an 18-0 victory last Wednesday against Nicaragua.

The Nicaraguans, like most teams facing Abbott for the first time, tested him. The leadoff hitter bunted to the left of the mound. But Abbott is accustomed to that. Leaving the inside of his glove balanced on his nub of a right hand, he fielded the ball with his bare left hand and threw out the runner by two steps.

“Fielding a bunt barehanded is a difficult play for a pitcher,” U.S. catcher Scott Servais said. “Jimmy does it routinely.”

Abbott laughed when someone suggested the Nicaraguans were less than sporting when they tried to bunt on him.

“The way I look at it, if a batter is weak on an inside pitch, I’ll throw inside,” Abbott said after the game. “If they feel I’m a weak fielder, then they should try to take advantage of me. I think of it as an easy out.”

The Nicaraguans did not try again, unlike a persistent team Abbott faced as a freshman at Central High School in Flint, Mich. The team bunted eight straight times. The first hitter reached first base; Abbott threw out the next seven.

“If you see him pitch a lot, you don’t even notice the hand,” U.S. Coach Ron Fraser said.

Abbott said even he can forget about it.

“I don’t even think about it until you guys come around to remind me,” he told reporters before a practice one day last week.

Talking to reporters is something else Abbott is accustomed to, having done his first interview when he was 12 years old in Little League. He said he does not mind.

“I like the attention,” he said, although it was clear he would rather be asked about his left arm than his right hand.

Of the hundreds of questions he has been asked since he arrived here, there is probably not one he has not heard before. But he is polite about it, patiently answering all of them.

“Everyone has limitations,” he said. “It’s just that mine are different from most people’s. So I learned to do things differently.

“When you’re little, learning to tie your shoes isn’t easy for anyone. But you learned, and so did I. I just learned to do it a little differently than you do.”

As for baseball, he said his worst moments are when someone hits a line drive back toward the mound.

Asked how he handles that, he smiled.

“I just duck,” he said.

“Seriously, there are some plays that are just tougher for pitchers to make than others. I know a lot of pitchers who have as much trouble as I do with line drives and bunts down the line.

“The only thing that bothers me is when a guy makes a good bunt, beats it out and then somebody says, ‘The pitcher would have gotten him if he had two hands.’ ”

At other times, he said he is amused by the comments he overhears.

“You get kids going down the line asking for autographs,” he said. “When they get to me, you can hear them asking each other, ‘Should I get his?’ I want to tell them, ‘I pitch! I pitch!’ ”

For his success, he credited his parents. His mother is an attorney, his father the manager of a beer distributor. They were both 18 and just out of high school when Jim was born.

“If they had ever discouraged me, even a little bit, I wouldn’t be here,” he said.

A few days later, his mother, Kathy, was asked about that.

“He always says that,” she said. “But all we did is let him do what he wanted.”

That began as early as kindergarten, when he insisted on ridding himself of a fiberglass artificial hand.

“The doctor told us if he didn’t have it, he wouldn’t be able to do things like tie his shoes and use scissors,” she said.

“But he didn’t like it. It frightened some of the other kids. Even the teacher expressed concern that he might hurt somebody with the hooks. He was self-conscious about it. We told him it was the best thing for him, but we finally gave up and quit making him wear it.”

After that experience, she said the other children accepted Abbott.

“That was when the bionic man was on television,” she said. “They associated the two of them with each other.”

She also recalled when she and her husband, Mike, encouraged Abbott to channel his athletic ability into soccer.

“We laugh about it now,” she said. “He didn’t like soccer. His brother, Chad (15), is the soccer player. The one sport Jim doesn’t need his hand for is about the only one he hasn’t gravitated to.”

He was particularly drawn to baseball, spending hours pitching a ball against a brick wall outside the family’s town house, practicing the fielding technique his father taught him so that they could play catch in the backyard.

Abbott uses the same technique today. As soon as he completes his follow through, he slips the glove, which has been resting on his fingerless hand, onto his left hand.

When the ball is hit toward him on the ground, he fields it, lodges the glove between his right arm and his body, takes out the ball and throws.

It may sound like a time-consuming process, but he does it so effortlessly that fans often leave his games with no idea of how he fields.

“I saw the game he pitched against Ohio State in Columbus last year,” said the Flint Central football coach, Joe Eufinger. “A lot of people went to the ballpark to see him, but, during the warmups, they couldn’t even pick him out from all the other players. Unless you see the stump, there’s nothing awkward about what he does.”

His parents were not aware of how much talent he had for baseball until he was 12, when they received a call from a reporter telling them that Jim was one of the best Little League pitchers in Flint.

“We hadn’t been paying much attention to what he was doing,” his mother said. “We just knew he was playing at the neighborhood fields and wasn’t getting into any mischief.”

By the time he was in junior high, he had caught the eye of Central High’s baseball coach, Bob Holec.

“The first time I saw him was in the city junior championship,” Holec said. “I was just as curious as everybody else. I wondered if he could handle balls hit back to him. I was talking to his father when a kid hit a high-hopper back to the mound. Jimmy threw him out.

“His father and I looked at each other, and I said, ‘I guess that answers that.’ ”

Already on the varsity baseball team by the time he was a sophomore, Holec talked him into playing football before his junior year because the team had no depth at quarterback.

“He had a good arm, obviously,” Eufinger said.

Abbott started the last three games of his senior year, throwing for 600 yards and 6 touchdowns, including 4 in a playoff game. He also punted as a senior.

“I honestly feel he is good enough as an athlete that if his first love was football he could have been a quarterback at the college level,” Eufinger said.

But his first love was baseball. Besides pitching, he also played first base, left field and even shortstop in high school. As a senior, batting cleanup, he hit .427 with 7 home runs.

“If I was a college coach, I’d definitely have him hitting,” Holec said.

Abbott was not heavily recruited by college coaches, not as much because of his right hand but because of his fastball, which was that in name only. He was clocked in the low to mid ‘80s. The Toronto Blue Jays drafted him out of high school in the 36th round, low for a left-handed pitcher.

Since then, he has filled out to 6-feet, 3-inches and 200 pounds, which has enabled him to improve his fastball to about 90 m.p.h. He was 11-3 with a 2.08 earned-run average while earning most valuable player honors for Michigan last season.

“I wouldn’t have recruited him if I hadn’t felt like he could play here,” Michigan Coach Bud Middaugh said. “But there was no way I could have known he was going to turn out like he has.”

As for whether he will be a high draft choice when he becomes eligible again at the end of next season, major league scouts who have watched him here are noncommittal. But they say nice things about him.

“The general public watches him because of his right arm, but the scouting people are interested in him because of the arm he throws with,” Terry Ryan of the Minnesota Twins said. “You have to take a look at him because he’s left-handed. He has good velocity and a good curve. He’s a good athlete, real strong and agile.”

Glenn Van Proyen of the Dodgers also praised Abbott’s pitching ability but pointed out the one liability that all scouts do.

“Even with one hand, he’s an adequate fielder,” Van Proyen said. “But the one thing you worry about is a line drive going right at his head.”

Abbott’s mother said doubters are not new to her son.

“The coaches have been skeptical at every level,” she said. “In junior high school, they told him he wouldn’t be able to play in high school. He got to high school and everyone had reservations about whether he’d be able to play in college.

“He’s doing well there, but we’ve told him this might be his last step. We’ve been very cautious. We’ve tried to instill in him that he’s got to think beyond baseball and get his education. I don’t think he’s ever been overconfident that he’s going to make it to the majors.”

Fraser, head coach at the University of Miami for the last 25 years, admitted he also had doubts before selecting Abbott to the national team.

“Ron called me and asked the same questions that everyone else does,,” Middaugh said. “I told him not to take Jimmy because of the attention he would receive but because he would be one of the team’s better pitchers.”

Fraser was convinced when Abbott beat world champion Cuba last month in Havana before a crowd of about 50,000.

“I don’t think they took him very seriously,” Fraser said. “They looked at him as a handicapped guy.”

They learned otherwise when the swift leadoff hitter, Victor Mesa, hit a high chopper down the third-base line. Abbott fielded it barehanded and threw out Mesa.

“Abbott’s a national hero down there,” Fraser said. “They’ll be talking abut him 20 years from now. When he left the game, he got a standing ovation from 50,000 people.”

Abbott said he does not know what was more memorable about his trip to Cuba, the game or shaking hands with Cuban President Fidel Castro.

Asked to compare Castro and Michigan’s football coach, Bo Schembechler, Abbott said: “Fidel’s a little bigger, about 6-4 and real wide. But they’ve both got sort of a tough guy, dictatorial presence about them.”

Abbott’s most exhilarating moment as a member of the U.S. team came when he carried the flag during the parade of nations at the opening ceremony here.

But he said he does not consider himself an inspiration, at least not to others with physical challenges.

“Sometimes I meet kids, like a kid I met in Miami, who had the same situation I have,” he said. “It’s really not that big a deal for us. It’s something we learn to live with.

“For parents, it’s different. Maybe I give the parents something to shoot for.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.