2-Room Office to Lofty Perch : The 100-Year Odyssey of L.A.’s Oldest Law Firm

- Share via

Amid the skyscrapers that tower over the legal and financial center of modern Los Angeles, one 25-story building stands as a symbol of both the city’s past and future.

The bronze and granite structure, completed in 1983 at a cost of $95 million, is the headquarters of O’Melveny & Myers, the first major law firm in the United States to build its own skyscraper home.

Today the firm, the oldest and one of the most prestigious in Los Angeles, has grown into one of the giant legal firms of the nation, with almost 400 lawyers competing for supremacy in the booming Southern California economy.

Among its thousands of clients are some of the largest corporations in the world. Its influence extends from its hilltop perch on Bunker Hill to Washington and New York, and as far away as London and Tokyo.

But it was a different world that spawned O’Melveny.

Los Angeles was a tough, brawling frontier town of 5,000 people in 1869--plagued with gambling, prostitution, armed vigilantes, several murders a week and occasional lynchings.

Among the town’s newest residents was Harvey O’Melveny, a judge in Illinois who had come west for health reasons. He soon became one of the town’s most prominent citizens, serving as president of the town council and one of the first judges of Los Angeles County, formed just two decades earlier.

Harvey O’Melveny’s son, Henry, was 10 years old when his family arrived in California. Following in his father’s career, he became the most prominent lawyer in Los Angeles for decades. When he died in 1941, he was eulogized both as dean of the California Bar and one of the men most responsible for the cultural and economic development of Los Angeles.

In recalling his life, however, Henry O’Melveny said his most colorful memories were of the early period in Los Angeles--the years that shaped both the city and the boy.

Rife With Violence

“From 1850 to 1870 Los Angeles was undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation,” O’Melveny wrote. “It contained a larger percentage of bad characters than any other city and, for its size, had the greatest number of fights, murders, lynchings and robberies.”

At the age of 11, the youth witnessed the last public lynching in Los Angeles. Other boyhood remembrances included the looting of Chinatown and the murder of 19 Chinese by a mob of 500 men a year later.

Because of his father’s prominence, Henry O’Melveny also was a witness to the political maneuvering that produced one of the most important developments in the young city’s history--the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

In 1872, Southern Pacific was threatening to build its main line from San Francisco through the Cajon Pass, north of Los Angeles, toward San Bernardino instead of into Los Angeles, bypassing the town and perhaps dooming its future.

The railroad wanted $600,000 to come to Los Angeles, and O’Melveny’s father was the chairman of a 30-member committee that worked out plans for a $377,000 bond issue and 60-acre land grant to meet the demand. The plans, however, were subject to a special election, with opposition from many residents.

“You will realize that the population of the city was then over 80% Mexican,” Henry O’Melveny wrote decades later. “The Mexicans not only did not understand the questions submitted at the election, but they did not care. It was just the common, ordinary practice to buy their votes. . . .

“On the night before the election, the anti-railroad people had impounded in a corral two or three hundred Mexicans whose votes they had purchased.

“The pro-railroad people, during the night, offered a larger price and bought the votes.”

Henry O’Melveny’s legal career began after graduation from UC Berkeley in 1879. Few lawyers went to law school in those days. O’Melveny taught himself from lawbooks and passed oral exams in 1881.

Small-Time Cases

Before starting his own firm, O’Melveny worked with two of the half-dozen other tiny firms then flourishing. His first case--a successful $175 damage suit against a man whose bull had gored a horse to death--reflected the cow-town legal practice of the day.

There were 80 lawyers in Los Angeles in 1885 when Henry O’Melveny became the junior partner of a two-lawyer firm founded by Jackson Graves and known as Graves & O’Melveny. They worked out of two rooms in an office building on Main Street called the Baker Block, then the center of the town’s legal world, now buried under the Santa Ana and San Bernardino freeways.

From the start, O’Melveny’s practice was built around banking and real estate. His father’s political ties and his own friendships included many of the city’s most prominent families: Dominguez, Sepulveda, Van Nuys, Hollenbeck, Slauson and Lankershim--an impressive list of early clients.

Then came the first great economic boom in Los Angeles, with the city’s population exploding from 11,000 in 1880 to 50,000 in 10 years.

“(It was) a period of the wildest speculation that any part of the United States ever had, relating merely to real estate,” O’Melveny added. “You could buy in the morning with the assurance that by nightfall you could sell for a profit.”

The boom of 1885 was followed by a bust a few years later. O’Melveny’s legal footing was secure, however, and he built a growing banking and corporate practice with the forerunners of such powerful firms as Union Bank, Security Pacific National Bank and the Southern California Gas Co.

By the early 1900s, Henry O’Melveny had become a leader of the Los Angeles legal world. He helped in the development of the state’s oil and hydroelectric industries, carved new cities from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach out of old Spanish landholdings and created the municipal bond business in Southern California.

Starts Own Practice

O’Melveny went into practice by himself in 1904, slowly adding lawyers over the next two decades. One of those was John O’Melveny, his son, who succeeded his father in running the firm. Another was Louis W. Myers, a former California chief justice, who joined in 1927 and ultimately became the firm’s second name partner.

The firm had grown to 22 lawyers by 1929, already a giant by the standards of the day. Its chief rival was Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, then an equally large and powerful firm that traces its own origins to 1890. Throughout most of the city’s history, they have remained the best-known law firms of Los Angeles.

Henry O’Melveny’s life--both professional and personal--was recorded in detail in his own writings as well as in a history of the law firm written in 1966 by O’Melveny partner William W. Clary. Apart from the law, the book makes clear, O’Melveny’s greatest passion was nature.

Early in his career, O’Melveny built a retreat in the San Gabriel Mountains and spent weekends there. Later he turned a 20-acre parcel in Bel-Air into his own private flower gardens, raising tulips and daffodils.

From 1927 to 1932, O’Melveny served on the State Park Commission and was one of the men most responsible for creating California’s present state park system. One modern tribute to his work is O’Melveny Park, a 714-acre wilderness area overlooking Granada Hills that was turned over to the city in 1973.

Henry O’Melveny gradually turned the management of the firm over to his son, John, beginning in the late 1920s, but he continued to work at his office until his death. The lawyers who worked with Henry remember him today for creating a family atmosphere within the firm that became a part of the O’Melveny heritage.

“There was nobody like Henry O’Melveny,” recalled Maynard Toll, 80, who joined the firm in 1930. “He’d get all the young fellows out to his farm and have them digging daffodil bulbs all day. That sort of thing just doesn’t happen anymore.”

Considered a Pioneer

Henry O’Melveny was 81 when he died, and he had practiced law in Los Angeles for almost 60 years. He was praised as “one of the city’s most illustrious sons” and accorded a pioneering role in the legal, financial and cultural development of California.

“I know of no man who has lived a more perfectly balanced life,” one columnist wrote. “His flowers are as widely known as his lawsuits.”

While Henry O’Melveny was building his law firm, John was studying law at Harvard, where he graduated in 1922. As O’Melveny’s newest associate, he was rewarded with a desk in the hallway and the paternal admonition that he would have to make it on his own. By 1926, however, John O’Melveny was the firm’s managing partner.

Because of the increasing size of the firm and his own Harvard background, one of John O’Melveny’s first moves was to institute a recruiting program at the nation’s leading East Coast law schools to build for the future. He also established business ties with the leading New York law firms that exist to this day.

While the firm’s practice began with banking, real estate and probate matters, John O’Melveny ventured into new areas of practice--most notably the entertainment business.

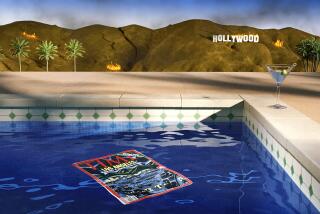

The law firm’s lasting Hollywood connections began in 1929 with Bing Crosby. Later clients included Mary Pickford, Alan Ladd, Ingrid Bergman, Jack Benny, Gene Autry, James Stewart, Gary Cooper and William Holden.

O’Melveny also built a strong institutional list of entertainment clients, including CBS, Paramount, Walt Disney Productions and Norman Lear’s Tandem Productions.

The firm’s involvement with Hollywood led to its first branch office.

Moving Up

In 1951, O’Melveny opened a tiny shop on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, next to Gene Autry’s production set. Six years later the office was relocated to Beverly Hills, then moved again in 1970 to Century City, now the center of L.A.’s entertainment law practice.

Deane Johnson, a leading O’Melveny lawyer for 40 years, was chief liaison to the Hollywood community. Joining the firm in 1942, he was one of the chairmen of the firm’s management committee after John O’Melveny’s retirement in the 1970s. In 1982 he left the firm to become president of Warner Communications.

“I think the golden age for me was the 1950s and 1960s. O’Melveny was the only downtown firm that did entertainment work in those days,” Johnson said.

“The firm was expanding and growing, but there wasn’t the same mood there is today. The character of law firms has changed. Some of the younger lawyers are motivated by the bottom line.

“To me the practice of law had to be fun,” Johnson added. “It’s such hard work that it’s not worth it if it’s not fun.”

However, the many complex cases that created O’Melveny’s reputation as the leading litigation firm in Los Angeles were hardly fun.

Several of the cases continued for decades, involved hundreds of lawyers and bounced from the trial courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. When the firm lost one particularly important case in the Supreme Court, it later turned defeat to triumph by lobbying Congress to change the law.

In that case, one of O’Melveny’s biggest, the fight was over oil rights in the three-mile tideland belt off the California coast, one of the most important economic disputes in California history.

The case, which began in 1937, started as a dispute between oil companies and the state. It became more complicated when the U.S. Interior Department decided in 1940 that the three-mile zone was federal property.

Supreme Court Defeat

In 1947, O’Melveny suffered a defeat when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had the “paramount power” over the three-mile belt. After a decade of continued litigation and lobbying, however, O’Melveny won a different Supreme Court ruling in California’s favor and the passage of two pieces of pro-oil-company legislation.

Playing a minor role in the tidelands case was a new associate, Warren Christopher, a former clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. In only a few years, however, he was winning some of the firm’s most important cases.

In the early 1970s, O’Melveny shifted to a committee system of management. John O’Melveny, who once called Christopher “the smartest lawyer” he had ever met, marked him as a future leader by naming him the committee’s youngest member.

At the time, O’Melveny was still generally viewed as the most prominent law firm in Los Angeles, ahead of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. However, Gibson, and Latham & Watkins, which had grown from a three-lawyer firm in 1934, had produced a new generation of leaders whose firms were moving up fast.

With the 1974 retirement of John O’Melveny and the firm’s switch to committee management, O’Melveny was no longer a family law firm. It had lost some of its prestige, part of its history and its most colorful character.

Just as his father was remembered for his flowers, O’Melveny, who died in 1984 at the age of 89, is recalled not only as a lawyer, but as a cattle rancher with a passion for breeding champion Irish bulldogs.

His son, Patrick, who rejected a legal career and is a vice president of Union Bank in San Francisco, said his father was really a cowboy at heart.

Love of Horses

“He always ran cattle. That’s what he really loved,” O’Melveny said. “He had me on a horse every day when I was growing up. In the 1930s, we’d keep the horses at what is now the Bel-Air Hotel. It was a stable in those days.”

Christopher, who became chairman of the firm in 1982, paid his own tribute to John O’Melveny in 1986 after the firm had celebrated its centennial anniversary.

“Jack started out to be a professor of philosophy,” Christopher said. “He often made light of his academic accomplishments by regaling his friends with stories about how his capacity to read philosophy was improved by an intake of Irish whisky.

“Despite Jack’s unique personality, it was always useful to remember his deep intellectual capabilities,” Christopher added.

“This was a man who rode horseback across the Rocky Mountains with his father and brothers, but who also maintained a lifelong friendship with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and other leading intellectuals of the time. The firm is his legacy to all of us.”

The contrast between O’Melveny and Gibson when Christopher joined the firm as its 50th lawyer in 1950 was far more dramatic than today. John O’Melveny was known as “Santa Claus” to the O’Melveny staff, often delighting secretaries by bringing them artificial trees loaded with cream puffs. Both O’Melveny and Deane Johnson had persuaded many lawyers to join the firm on charm alone.

At Gibson, meanwhile, the recruiting style was more austere.

“The difference was the atmosphere,” said William Vaughn, who joined O’Melveny in 1955 and now heads the firm’s litigation department. “From the moment I walked into O’Melveny, I felt at home. Gibson seemed more tense and the leaders were less friendly.” Despite the image, O’Melveny was as rigid politically and socially as most of the leading corporate law firms at the beginning of the 1950s. During World War II, out of necessity, three women lawyers had been hired. But there were no women partners. Nor where there any Jews, blacks or lawyers who could be considered political activists.

Breaks the Mold

In many respects, Christopher broke the O’Melveny mold.

He did not possess the back-slapping, gregarious nature of the firm’s founders. Nor were his outside interests as esoteric as flowers or bulldogs. His interests were the law and Democratic politics, and he was the first O’Melveny lawyer to successfully mix the two.

Christopher’s arrival coincided with the beginning of some dramatic changes in the firm. He quickly became a key adviser to leading Democratic politicians and, later, a prominent political figure himself.

But his politics never seemed to trouble even the most conservative O’Melveny partners.

“There had always been a sense at O’Melveny that lawyers were lawyers and politicians were politicians,” said Henry Thumann, a leading antitrust lawyer who joined the firm in 1960.

“Chris was the first person to bridge that. Partly it was because he was so respected as a lawyer. Two-thirds of the partners back then would have been Republicans and Chris was a very active Democrat. But he did it without bringing it into the workplace.”

As a lawyer, Christopher’s most important work was in the legal battle that erupted in 1959 with the arrival of jet passenger travel to Los Angeles, a development opposed on grounds ranging from noise pollution to federal interference with local regulatory powers.

Partly because of Christopher’s connections from his Supreme Court clerk days, the New York firm of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, coordinating strategy for the nation’s airlines, selected O’Melveny to fight a rash of lawsuits filed by citizen groups and municipalities to try to ban jets from California.

The battle was fought on three fronts. The firm’s first victory was on the noise pollution issue in a case involving jet takeoffs from Los Angeles International Airport. Its second success in a case handled by Christopher was a state Supreme Court ruling in 1964 that blocked efforts to ban jet flights into San Diego. Finally came the City of Burbank vs. Lockheed Air Terminal, another victory for the airlines decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973.

Wins All 4 Cases

The Burbank case, still reverberating in legal circles, was one of four argued by Christopher before the Supreme Court. He won them all.

Christopher’s career with O’Melveny, however, took a series of starts and stops beginning in the 1960s, which carried him away from the law firm for years at a time while the legal community of Los Angeles was beginning a period of dramatic transformation.

In 1965, Christopher put together the McCone Commission, which studied the Watts riots. He was its vice chairman. He also served from 1967 to early 1969 as U.S. deputy attorney general, the second-highest official in the Justice Department and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s adviser on urban violence.

He returned to O’Melveny for six years in the early 1970s but left in 1976 to serve again as U.S. deputy secretary of state, this time in the Carter Administration.

Christopher’s diplomatic assignments ranged from negotiating the Panama Canal Treaty to working out the details of the release of U.S. hostages in Iran in the closing hours of the Carter presidency in January, 1981.

When Christopher returned to O’Melveny a few months later he was an internationally respected statesman and had won the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award.

But the legal profession had changed radically in Christopher’s absence, and O’Melveny had been slower to adjust than many of its rivals. Christopher’s challenge was to mold the city’s oldest law firm along more competitive lines as quickly as possible.

“I had stayed in touch with my friends during my years in Washington, but I had not followed the practice,” Christopher said. “I really didn’t realize how much the legal profession had changed.”

Times research librarians Susanna Shuster and Tom Lutgen contributed to this story.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.