MINNESOTA TWINS : Calvin’s Kids Made the Difference

- Share via

MINNEAPOLIS — Calvin Griffith sits behind a cluttered desk in an office decorated with precious few of the trappings of 75 years in baseball, from his days as a bat boy for the 1924 Washington Senators to those as an owner of a family-run enterprise called the Minnesota Twins.

On one wall is a picture of Clark Griffith, Calvin’s dad and the former Senators’ owner. On another is an autographed picture from Rod Carew: “To Calvin, Thank you so much for having faith in me. ... “ -- Rod.

And there is a small plaque with the words: “When I am right, no one remembers. When I am wrong, no one forgets.”

In this the Twins’ finest hour in 25 years, the autumn they’ve returned to the World Series, it would be easy to dismiss this open, friendly old man with the beefy jowls and ample belly. It would be easy except that the celebration of baseball in Minnesota has again thrown the spotlight into a small Metrodome office far from the Twins’ current powers that be.

It may be Griffith’s final legacy that it was he who was the architect -- although not the finishing carpenter -- of the 1987 American League champions.

It was Griffith who looked free agency in the eye and didn’t blink. He said goodbye to Larry Hisle. And to Carew, Lyman Bostock and Dave Goltz. They all had million-dollar offers elsewhere, and he let them go.

“Except for Bostock,” he said. “We offered him more money. That was a guy that could win games for you.”

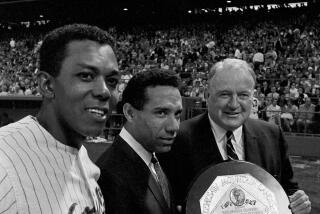

Griffith’s legacy may be that he introduced the 1987 champions in 1981 and 1982. He brought third baseman Gary Gaetti to the big leagues at the age of 21, first baseman Kent Hrbek at 22, catcher Tim Laudner at 23, pitcher Frank Viola at 22 and center fielder Kirby Puckett at 23.

They were all here before their time, and when their time did arrive, Griffith had sold the team to a Minneapolis banker named Carl Pohlad. Yet he remains part of the celebration. He says people are stopping him on the street to congratulate him. And he says proudly that Pohlad invited him to accompany the team to Detroit for the playoffs and St. Louis for the Series.

“Oh, did I catch hell for bringing these kids up,” Griffith said. “But all these boys had ability, and all they needed was to get an opportunity. We’d always catered to youth here. We felt we had to.”

He said he sold the Twins on Sept. 7, 1984, because “I could see the handwriting on the wall. These kids were developing good, and their salaries were going to start getting up there. No, I don’t have any regrets. I saw the money getting scarcer.”

Three years after Griffith sold the Twins, they may be a model franchise. They have the game’s youngest general manager (34-year-old Andy MacPhail). They have its youngest manager (37-year-old Tom Kelly). They have hired an aggressive sales and marketing department, and MacPhail has overhauled their farm system.

Pohlad has also sent a message to the clubhouse: Perform well here and you’ll be paid well enough to stay. Ask Hrbek and Gaetti, both of whom re-signed with the Twins instead of pursuing offers through free agency.

Ask baseball people and they’ll tell you the Twins have hired some of the brightest, hardest-working people in the game, that when their farm system gets rolling in a couple of years, they should have a steady flow of talent.

When Calvin Griffith owned the Twins, they were a family operation. He had brothers and sisters and nieces and nephews working here and working there.

The Twins were not simply part of his corporate world, they were his corporate world. Most days, Griffith took his lunch and dinner at the stadium, then stayed after hours to chat with whoever stopped by.

No one is quite sure how the Twins got by. George Brophy was a top-notch personnel man, but his collection of scouts was loosely organized and required to submit only minimal information about a prospect.

When MacPhail came in, he was stunned to see they had only about nine scouts covering the country.

“We had two scouts working South Dakota,” MacPhail said. “That state produced less than one player a year. We had none in Texas, a state that produces about 57 a year.”

But as Pohlad and others came in, they found what an amazing operation Griffith had run. Books were kept mostly in his head. Contracts were negotiated on cocktail napkins. Draft picks were many times selected intelligently, many times on hunches. The hunches hadn’t paid off and the farm system was threadbare for a couple of years.

Now, the Twins have computers and charts and a think-tank of a front office. MacPhail’s brainchild was to bring in Terry Ryan from the Mets to serve as director of scouting. Ryan was a former Twins pitcher with a reputation as a keen judge of talent. Together, they set up new departments for scouting and player development. On MacPhail’s office wall are the rosters from all 26 teams in baseball, with colors signifying whether the player is left-handed, right-handed or a switch-hitter.

Since Pohlad bought the Twins, their payroll has tripled to more than $4 million. No one calls them a mom-and-pop operation anymore.

“They’ve got so much help around here you can’t believe it,” Griffith said. “I look out there and three secretaries are chewing the fat or reading a book. I think, ‘Jesus Christ, he’s paying them good money.’ It’s like Washington and all those bureaucrats sitting around getting nothing done. I had family working here, and long hours meant nothing to them. Now, everyone punches a clock.”

He says MacPhail occasionally comes by to ask his opinion on things, but “I think (he) already has his mind made up before he asks. No, I’m not really part of it. If I were part of it now, I think they’d ask me questions. But I’m happy. What the hell, I’ve got this office, got a box where I can watch games. I’m entitled to eat lunch and dinner at the cafeteria here. I don’t have to go out all the time.”

MacPhail is the son of former American League president Lee MacPhail, and like his father, his reputation is that of an intelligent, open man. He came here having never made a trade, but he had watched while working for San Francisco general manager Al Rosen (when both were at Houston).

He’d also gotten to know Tal Smith, a respected baseball man who’d once been the Astros’ general manager. MacPhail said his knowledge grew a bit at a time, but that one of his earliest lessons was of the importance of a farm system.

So when he joined the Twins, he hired scouts, personnel and scouting directors and set up a new system for finding and evaluating talent.

“Our scouts fill out game reports that are more detailed,” he said. “I don’t think there’d been that much of a sense of procedure before. A lot of things were done informally.”

His work with the farm system may not pay off for three or four years. What he impressed everyone by doing last winter was trading for reliever Jeff Reardon and outfielder Dan Gladden and signing reliever Juan Berenguer, all keys to the ’87 championship team.

MacPhail doesn’t duck the credit he deserves, but he passes some around.

“Anytime a team gets to the World Series, it’s because of a chain of events,” he said. “Here, you’ve got Calvin Griffith and George Brophy and Carl Pohlad and Andy MacPhail.”

It was Griffith and his people who drafted the Gaettis, Hrbeks and Violas. It was Pohlad who has kept them here. It’s MacPhail who made the deals to fill in the other pieces.

“Tal Smith told me the two important factors of a baseball team were how you played on the field and how the public perceives you,” MacPhail said. “We got Berenguer in January, Reardon in February and Gladden in March. Then this season, we got Joe Niekro and (Steve) Carlton. The perception was that we were always trying to improve.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.