Rabin: He’s A Real Yes Man

- Share via

“I’m a man without a land,” Yes’ guitarist-songwriter Trevor Rabin concluded with a grim smile. “It’s a strange feeling. I’m not sure I can explain it.”

But he tried anyway.

During a recent interview, Rabin started out talking about Yes’ new Atlantic Records album, “Big Generator,” and wound up talking about something he said he’s never discussed at length with the media--his feelings about being a displaced South African. It’s not even widely known, he added, that he’s from South Africa.

Rabin, 32, who’s anti-apartheid, left his homeland in 1978, living in London for several years before moving to Los Angeles, which is still his home. He lives in the Hollywood Hills with his wife, a South African, who emigrated with him, and his young son, who was born in America. Though still a citizen of South Africa, he plans to apply for U.S. citizenship.

Rabin said he’s sometimes not sure where he belongs. “I don’t consider myself a South African anymore. Someone commented that I have a nice accent and asked where I’m from. Unconsciously I said London, because I lived there for three years.

“I belong in America more than South Africa. I can’t remember the feeling of living there anymore. It’s like it was in another life. That’s sad in a way. It is my country. It’s where I grew up. You don’t know what it’s like to have these negative feelings about your homeland. There are roots you can’t escape. I hate what’s happening there now. But if things ever changed, I’d go back there and live.”

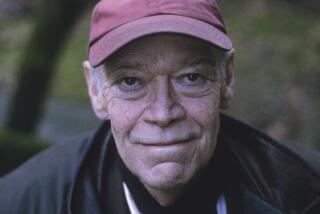

Rabin is a tall, handsome, friendly man with a remarkably gentle manner. Nonchalantly sipping Sherry at a restaurant, he was talking about an emotionally charged subject, but his emotions weren’t on the surface. But that didn’t mean he was detached.

“Maybe it doesn’t show, but I feel this very deeply,” he said. “I don’t live there but I carry South Africa with me.”

White South Africans, he said, are a target: “You’re a white South African and right away you have to explain yourself. Occasionally I get hassled until I explain my point of view. I have to make it clear that I don’t live there anymore and I don’t approve of the brutal racial policies.”

Rabin grew up in Johannesburg in a liberal family that always opposed apartheid. His first cousin is editor-writer Donald Woods, whose friendship with late black South African activist Steven Biko is chronicled in the just-released movie “Cry Freedom.”

According to Rabin, his relationship to Woods has rarely been publicized. Though Rabin admitted he hasn’t seen him in years, he vividly recalls Woods’ ordeal. “I remember when his family was sent T-shirts with acid on them,” he said of a horrifying incident depicted in the film. “They called my mother and she was sitting there crying. You don’t forget things like that.”

Rabin was a star in South Africa in the mid- ‘70s, with an enormously popular pop band called Rabbit. But he wasn’t fully savoring stardom because dissatisfaction about apartheid was gnawing at him.

“You can’t be there and be in that situation and not feel bad about it,” he said. “It’s a beautiful country but there’s this dark cloud over it that won’t go away.”

It wasn’t only the government’s racial policies that bothered him. “I’m Jewish,” he said. “Rabin is from Rabinowitz. There’s a lot of anti-Semitism there. But that’s minor compared to what’s happening to the blacks there.”

An incident with a black female singer was the last straw for Rabin. When he finished producing an album for her, they went out to celebrate. “We couldn’t eat at the same restaurant,” he recalled. “It was horrible. It was embarrassing. I knew then that I had to get out.”

It was not a quiet exit.

“There were a million media people at the airport, asking all kinds of questions,” he said. “All I knew was that I was getting out of there and going to London.”

Somewhat apologetically, Rabin said he’s not an activist. “I’m a musician. I spend my time with music. I’m not comfortable with being an activist. But there are things I would do. Like I would have been part of that (anti-apartheid) ‘Sun City’ single project. I would have done it in a minute if I had been asked. But I wasn’t.

“And there are things I won’t do, like play Sun City. They asked Yes to do it but there’s no way. That’s indirectly sanctioning that whole system and I could never do that.”

Rabin’s best friend is pop singer Manfred Mann, another South African refugee who opposes apartheid. But Mann, Rabin said, is a political radical. “I worry about what might happen to him if he goes back there.”

Rabin returns to South Africa occasionally to visit his parents--with as little fanfare as possible. “I sneak in and out of the country,” he said. “I get nervous there. I wonder when I’m going to be pulled aside and asked about my views.”

Does Rabin fear reprisals against his parents if he were to become extremely vocal about his opposition to the South African government?

“There’s always that chance,” he replied.

Yes’ new album, “Big Generator,” is its first since “90125” in 1983. Like “90125,” which has sold nearly 4 million copies, it’s another highly commercial pop-rock effort.

Rabin, the chief songwriter, has been a major force in resurrecting this band, which had been one of the progressive-rock titans of the ‘70s. By the early ‘80s, it was buried deeply in the rock ‘n’ roll graveyard.

Under Rabin’s influence, however, Yes switched to accessible pop-rock. “At first people were screaming, ‘You’ve ruined Yes, you’ve ruined Yes,’ ” Rabin recalled. “But what’s happened is that Yes has just adopted a more modern sound.”

Some of Yes’ music is even dance-oriented. Many dance fans regard the dance mix of “Owner of a Lonely Heart”--a No. 1 pop single in 1984--as one of the best 12-inch singles ever made. In its heyday in the ‘70s, Yes wouldn’t even have played something like “Owner of a Lonely Heart” in jest.

In those days, Yes was grandiosely merging rock and classical music, producing a highbrow hybrid that enthralled those who preferred their rock symphony-style.

By the early ‘80s, the market for this music shrivelled. Yes was in mothballs in 1982 when two former Yes-men, bassist Chris Squire and drummer Alan White, assembled a pop-rock band called Cinema. Their first recruit was Rabin.

At the time Rabin was floundering. His hard-rock solo albums on Chrysalis had been acclaimed but sold poorly. But he did have a development deal with Geffen Records, which wanted to put him in Asia, a supergroup then being assembled.

“I didn’t want to do it,” Rabin recalled. “I didn’t like much about that band. I knew I’d lose the Geffen deal if I didn’t join Asia. But I still refused.”

Soon he was a man without a label. So the offer to join Cinema seemed attractive. “I went to London and we played together,” Rabin recalled. “It sounded terrible, but it felt good. So we went ahead and did an album.”

At the time, Cinema included Squire, White and keyboardist Tony Kaye, all from Yes. Then they recruited the old Yes singer, Jon Anderson.

“With Jon in the band it really sounded like Yes,” Rabin said. “So we decided to call it Yes. But it’s not really like Yes. I helped change that--which is something I’m really quite proud of. I remember Rabbit, the band I was in back in South Africa. I’ve come a long way.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.