Looking Forward to a Backward Marathon

- Share via

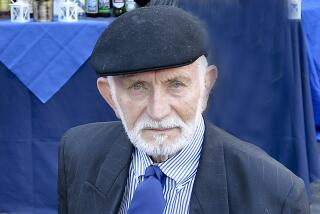

A veteran marathoner, Albert Freese was definitely looking to turn his life around.

“After completing the Western States 100-mile run from Squaw Valley to Auburn, Calif., in 1984, I thought there was only one thing left to accomplish, and that’s running backward,” said Freese, a 41-year-old electronics technician from Seal Beach.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Nov. 26, 1987 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday November 26, 1987 Home Edition View Part 5 Page 21 Column 3 View Desk 1 inches; 16 words Type of Material: Correction

The name of Nancy Ditz, female winner of the first two Los Angeles Marathons, was misspelled in View on Tuesday.

A few months later, he lined up tail-first in the 1985 Long Beach Marathon and finished the course in 4 hours, 9 minutes and 7 seconds, only 73 seconds off the world retro-running or running-backward mark of 4:07:54. From that point, Freese has enjoyed the challenge of living life on the flip side.

“Running backward in a marathon is like running 45 miles forward,” said Freese, whose California license plate spells MR BKWD. “When you run frontward, you can look and see where you’re going. You can daydream about anything you want. You can change your stride or slow down or put it into automatic.

“Running backward, you physically and mentally have to be on your toes. Every step that you take has to be very, very exact. For one thing, you are going a different way from everybody else. It’s easy to run along with the crowd, but when you’re different, it’s more difficult.”

Running Maverick

Freese’s reverse psychology makes him a running maverick, but retro-running is gaining in popularity among more mainstream runners as a fitness craze and as a training supplement to forward running.

Its supporters claim it improves muscle balance, promotes healing of injuries, enhances aerobic conditioning and increases caloric expenditure.

Rod Dixon, New Zealand’s Olympic medalist in the 1,500 meters in 1972 and winner of the New York City Marathon in 1983, has long used retro-running in his long-distance training. He compares its benefits to those of doing leg curls and leg extensions in the weight room.

“I think it is so very necessary to work every muscle group and exercise them in a balanced way,” said Dixon, who is currently training for the L.A. Marathon, which he hopes to use as a springboard for the 1988 Olympics.

Fred Lebow, president of the New York Road Runner’s club and founder of the New York City Marathon, does an about-face after he hits the so-called runner’s wall about 18 to 20 miles into a marathon.

“In the past I would normally go into a walk,” Lebow said. “Now I do retro-running. It gives your forward-moving muscle fibers a chance to turn around.”

Frank Shorter, winner of the marathon in the 1972 Olympics at Munich and a track-and-field analyst for NBC at the recent World Games in Rome, counsels caution before taking the backward plunge.

Motives Important

“My instinct is not to discount its validity,” Shorter said, “but it is important to know what is the motive of the person making the claim. Is the person a sports physician from Ball State who has done serious research in the lab or is it someone from Hermosa Beach who is running backward in the sand?”

Nancy Deitz, the female winner of the first two Los Angeles Marathons in 1986 and 1987, lines up on the side of Shorter.

“I have enough trouble finding the hours in the day to run forward,” Deitz said.

Dr. Barry Bates, founder and director of the University of Oregon’s biomechanical and sports-medicine laboratory in Eugene, Ore., has given retro-runners a strong leg to stand on, confirming with his stop-action projectors, graphic digitizers and scientific data what many have claimed from experience.

“We thought if we’re really supposed to be the gurus of running, in the running-injury business, that we may as well take a hard look at all these claims,” Bates said.

Basically, Bates limited his investigation of retro-running to the lower extremities, the hip, knee and ankle joints and their supporting muscle groups. Specifically, he wanted to know whether retro-running could be used as a tool in both rehabilitation and sports conditioning.

In two separate studies, he found that the range of motion in the hip is greatly reduced.

“Right away, you can see how that might do some good for someone with a hip injury,” Bates said. “They can perform, but they are not stretching things out as much.”

The knee, on the other hand, undergoes an increased range of motion, Bates said, but remains stable during the critical first third of movement until shifting into a better position for push-off.

Lots of Muscle Activity

“For postoperative knees,” Bates said, “doctors want to get a lot of muscle activity around the knee joint without a lot of movement, especially during the initial impact phase when the knee is most vulnerable. Retro achieves this.”

Retro-running, it turns out, supports the ankle in a similar way. The range of motion increases in the ankle, but the ankle is flexed in a relatively fixed position in the initial impact or support phase.

“If you had a typical sprained ankle, where you go over the outside, walking backward, as a first stage to get the function back, works quite well,” he said. “You are basically stabilizing the ankle joint against the same trauma that disrupted it.”

Running backward produces a softer landing than its forward counterpart. And because retro-runners land on the ball of the foot, the impact is cushioned by the calf muscle instead of the ankle, knee and hip.

Bates also found that running backward strengthens the hamstring, which is the muscle that propels the leg in retro-running. A strengthened hamstring is less prone to injury and a better complement to its opposite muscle, the quadriceps, used in forward motion.

“You get some nice, natural stretch going backward that you don’t get going forward,” he said. “We’ve seen baseball pitchers using some backward jogging and running to strengthen their hamstrings to avoid an injury later.”

Gary Gray, a physical therapist, athletic trainer and triathlete, estimates he has treated thousands of patients at his Adrian, Mich., clinic, using a variety of retro therapy in the last 12 years.

“We started out using it simply because it just seemed easier to get some of our patients moving backward first,” Gray said. Initially, he treated only stroke victims with retro techniques, but soon broadened its application to include patients with hip fractures, knee injuries and ankle sprains.

“As a complement for developing muscle balance and a more fluid motion, it helps our patients get back on their feet,” Gray added.

Therapy Session

Gray typically charges $35 for a 1 1/2-hour therapy session, which includes videotaping the patient’s afflicted body part. Accordingly, he said a big city clinic would charge three or four times that amount.

Once healthy, these runners may turn their back on conventional running forever because retro-running increases aerobic activity and burns additional calories. A recent study by exercise physiologist Fred Andrews at the University of Toledo revealed that the mean heart rate of his forward-running subjects rose from 162 to 183 when they ran the same pace backward.

“We were able to prove that the perceived difficulty of backward running is not psychological but physiological,” Andrews told Peggy Miller of Runner’s World Magazine.

John Arce, the head conditioning coach at UCLA, believes that as more marathon runners guard against overuse syndrome to prolong their careers, they will substitute the volume and mileage of their training with shorter, more intense workouts.

“We use some back running in our speed programs from 30 to 60 meters,” said Arce, who oversees training and conditioning programs for 235 different sports at UCLA. “It’s basically a biomechanical drill to enhance hamstring and quadriceps strength and to increase the arm pump.”

Other athletes who routinely use retro-running in their training programs are basketball and soccer players and defensive backs in football, Arce said.

Most proponents of retro-running aren’t trying to break new ground. They simply believe that running backward is in step with the latest training and rehabilitative programs.

“Every time I mention it to a coach, they just laugh,” Lebow said. “I honestly don’t know why more of them don’t recommend it.”

There may be a few reasons. World-class athletes tend to emphasize specificity in their training. Practice makes perfect, in other words.

‘Lots of Repitition’

“To be good in any sport, to be world class in anything,” Deitz said, “takes a lot of repetition in your event.”

Shorter agreed. “If you’re a swimmer, swim. If you’re a biker, bike. If you’re a marathoner, run. If you’re a triathlete, do all three.”

Shorter cited other obstacles in the path of retro-runners: parked cars, potholes and pedestrians. “I never really trained backward,” Shorter said, because I’m worried about not being able to see.”

Bates alternates walking forward and backward on a treadmill in his basement. Gray runs in the country where he has long stretches of the road to himself. On a track, Dixon runs backward only on the straight aways, called retro-straights.

Outdoors, Gray advises moving the head side-to-side, looking over one shoulder, then the other to prevent neck strain.

Despite these running tips, an increasing number of retro-runners are bringing on their own downfall as competition in their sport heats up.

Two runners fell as they tried to accelerate into a turn in the New York City Racquet and Health Club’s first one-mile retro-run in Battery Park last April. They were more embarrassed than hurt, according to Lebow.

Lebow would rather focus on the aesthetics of the race.

“The start looked like the finish,” Lebow recalled. “At the start of a normal race, the runners are poised and crouched. In retro-running all you see are backs with faces looking sharply to the left or right. It was really weird.”

It is likely that Deitz, Dixon and Freese will all meet in the 1988 L.A. Marathon, although admittedly their aims for running will be quite different. Deitz will try to be the fastest woman, Dixon the fastest man and Freese the fastest retro-runner. And their individual goals will directly influence how they train.

Deitz will average about 100 miles a week running forward when she’s not working as a television reporter for KPIX in San Francisco. Dixon will use a combination of forward and backward running to prepare for the March 6 race, which New Zealand has designated as its official Olympic trial.

“There are no shortcuts to running,” Dixon said. “Retro-running is not going to make you a better runner because you do 16 miles of retro a week. It’s all part and parcel. You’ve got the pie. You’ve got all the segments. Every part plays an important part in the training. Remembering all the little details, all the little secrets of putting it all together, is the key.”

Freese recently put a blanket over his television and moved it into the garage. Wearing his Humphrey Bogart hat, he has begun running backward 17 miles a day in the Seal Beach sand, with shorter trips backward to work and the local grocery store. As the L.A. marathon nears, he will call the editors of the Guinness Book of World Records to inform them of his latest assault on the record.

“I’m still running against everybody,” said Freese, who jokes that he is “looking forward, I mean backward” to the showdown. “I’m trying to pass as many people as I can. As I go by, I like to tell ‘em I’ll drop ‘em a line when I get to the finish.”

Freese, who has four teen-age children, confesses that none of them yet runs backward: “Yeah, but they all surf backward.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.