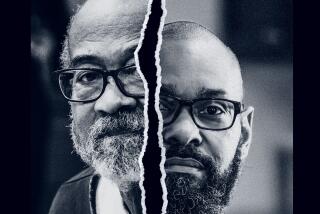

Millions in Settlements and Verdicts Reaped Over 54-Year Career : ‘The King of Torts’ Has No Plans to Abdicate

- Share via

Melvin Belli’s client, a young convict at San Quentin named Ernie Smith, was on trial for killing another inmate on the prison yard. Smith claimed that the inmate had a knife; the prosecution said the victim was unarmed.

Belli had been practicing law only a few years, and the case was one of his first big trials. He wanted to prove to the jury that it was likely the man had a knife--and that Smith had acted in self-defense--because weapons were so common in prison.

Belli carried into court a box filled with knives that had been confiscated from prisoners. As Belli walked toward the jury box, he pretended to trip and stumble, and the dozens of nasty-looking, jury-rigged knives--steel bedsprings with tape handles, sharpened files, broken saw blades--clattered onto the floor.

He slowly picked up a knife, examined it, sighed and tossed it into the box. Then he picked up another knife, and another, until, one by one, he had filled the box.

‘Knew in an Instant’

“The jury saw right there that knives were commonplace in prison and knew he wasn’t guilty,” Belli said in an interview, briefly closing his eyes and recalling the 50-year-old case. “It may have taken me forever to talk the jury into seeing my point. But when they saw all the knives on the floor, they knew in an instant that it was self-defense.”

Belli was so impressed with the impact the box of knives made on the jury that he soon began pioneering the use of demonstrative evidence in civil cases. And through his innovative use of the graphic evidence, he became famous for winning enormous damages in personal-injury cases. “Show it, don’t tell it” became his motto.

Belli brought blackboards into the courtroom to help juries compute damages. He showed them aerial photographs and he built scale models of intersections where accidents had occurred. He pushed tiny cars and trucks to explain the cause of accidents. He showed juries enlarged X-rays of accident victims and explained their injuries. He introduced “day-in-the-life” films, which detailed the problems faced by the injured and maimed.

“We brought medicine down to the terms of the layman,” said Belli, who often discusses his accomplishments using the collective we. “Before, it was more telling than showing, more formality than realism. We tried to get rid of all mumbo jumbo and show what really happened.

“If the leg was traumatized, we decided to show the leg. If it was gone, we showed the stump. Jurors were able to really see the extent of the injuries and, as a result, my clients began getting much bigger awards. We raised the value of loss of limbs, pain and suffering.”

‘Structured Settlements’

Belli began winning enormous verdicts by asking for “structured settlements,” which detailed future medical and living expenses and the sums needed to support the plaintiffs during their lives.

And he has won a number of precedent-setting suits. In 1944, he represented a waitress who was injured by an exploding Coke bottle, a landmark case that created today’s product-liability law. Traditionally, the plaintiff had to prove exactly how a company was negligent and how the negligence caused the injury.

But Belli applied the legal theory of res ipsa loquitur-- the thing speaks for itself. He argued that the Coca-Cola Bottling Co. was responsible even if it could not be determined what was wrong with the particular bottle. The courts agreed, and the case set the precedent for assigning liability without proof of negligence.

By the mid-1950s, Belli had revolutionized personal-injury representation to such an extent that Life magazine dubbed him “The King of Torts.”

Belli estimates that he has won $350 million in verdicts and settlements over his 54-year career. His biggest victory so far is $27 million, for twins who were brain-damaged at birth. He works on contingency, and his fee usually is from one-quarter to one-third of any verdict or settlement. Belli needs the huge settlements to support his lavish life style. He lives in a Pacific Heights mansion with his fifth wife and 14-year-old daughter, drives a Rolls-Royce and spends weekends on his 105-foot yacht.

No Plans to Retire

His firm has been beset by problems in recent years, but Belli has no plans to retire. He still spends long hours in his enormous office that dominates the 160-year-old, red-brick Belli Building.

Belli’s office looks like a cross between a brothel and a curio shop. The drapes are red velvet, and four glass chandeliers hang from the ceiling; a stuffed tiger is perched on the sofa and a stuffed water buffalo leans against a wall. An antique mahogany bar lines one side of the office and shelves above the bar are crammed with souvenirs from his travels: primitive masks, empty bourbon bottles, a New Jersey license plate, aborigine shoes from Australia, name tags from legal conventions, stuffed parrots, strings of garlic, Turkish fezzes. . . .

He spends his days punching the speaker phone and conferring with clients, barking orders to the lawyers and paralegal aides who parade in and out of his office and taking calls from reporters about Jim and Tammy Bakker or other topical clients.

Belli once had an exceptional sense of recall. When associates discussed their cases with Belli, he was known for his quick comprehension and his ability to cite landmark decisions--the dates, names and key legal issues--that would apply.

But now his memory is spotty. If he cannot recall the details of a past case, he tells a visitor: “Look it up in the books. It’s all there.” Belli has written 62 books on trial procedure and his experiences in court.

“The early books, I wrote all of them,” he said. “The later books, I wrote none of them. I’d just sit and talk with him (his collaborator) and he’d run a machine.”

Flashes of Charisma

But Belli still shows flashes of the charisma and presence that made him “The King of Torts.” He is a stout, barrel-stomached man with a shock of white hair, and when he strides into a courtroom, wearing his black snake-skin cowboy boots and trademark black double-breasted suit with red silk lining and red silk handkerchief, people take notice.

And when he discusses an issue he feels passionate about, he still is a powerful advocate. His voice is deep and sonorous, and he can bellow with righteous indignation over what he calls the greed of insurance companies or, voice softening, discuss with empathy the plight of a paraplegic client. During his monologues, he rarely looks at his visitor; instead, his eyes are fixed on a corner of the room, as if he is addressing an invisible jury.

Belli made his reputation by being able to keep the attention of a jury. One of his most famous legal victories involved a woman who had lost her leg in a streetcar accident. When the trial began, Belli walked into court carrying a large rectangular package wrapped in butcher paper and tied with string. Each day he carried the package into court and, occasionally, moved it from one end of the counsel table to the other.

The jury was intrigued. And horrified. Had Belli brought the amputated leg into court?

Finally, when the defense attorney finished arguing that the woman would be able to live a normal life because of the wonders of artificial limbs, Belli began to slowly untie the package. Then he suddenly pulled the woman’s artificial leg out of the paper.

“This,” he said, dumping the limb into the lap of a juror, “is what my pretty young client will wear for the rest of her life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.