PERFORMANCE ART REVIEW : Charlip’s Extravagant ‘Amaterasu’ at MOCA

- Share via

Somewhere inside Remy Charlip’s “Amaterasu” is a simple, chaste performance-art parable about the power of art to enlighten, informed by Charlip’s deep compassion for human frailty. But what premiered Thursday at the Museum of Contemporary Art was mostly a misguided Spielbergian extravaganza reeking of money, technology and confusion.

Based on the Japanese myth of a sun goddess who withdraws from the world, “Amaterasu” presents Charlip as narrator, commentator, actor, dancer, graphic artist and stage magician, retelling the story through different disciplines. He plays all the roles, though Anatto Ingle and Kedric Robin Wolfe aid and supplement his performance.

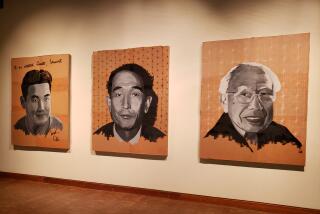

A lobby exhibit includes drawings by Charlip and designer Steven Arnold that depict characters, environments, transformations in the narrative and the plans for some of Charlip’s choreography as well. Spoken passages, a whimsical puppet show and, finally, a dance drama reiterate themes of male rage and female isolation, themes also embodied in the contrasts of Carl Stone’s electronic score.

But curious distortions soon occur--sometimes literally, as when the MOCA loudspeakers make Stone’s music sound tinny, sometimes thematically as when the icons of female power in the story are robbed of sympathy or stature.

Charlip understands the outburst of male destruction in the myth: When you live in slime, you become slime. But he portrays Amaterasu’s response to violence only as campy petulance (“Oh, what a mess !”) and her eventual return to the heavens as sheer ego (“The world can use my light, but more important, I need to shine again”).

In a long spoken interlude, Charlip is quick to relate the story to gay liberation, but he never explores the far more pertinent parallel between Amaterasu’s withdrawal and the early phases of the feminist movement. Instead, the goddess becomes a capricious figure who punishes everyone by refusing to directly express her anger.

By personalizing the myth in this manner, Charlip has diminished it and the overscale production values are no compensation.

Arnold has given Charlip ramps and towers, a star-spangled backdrop and (with lighting designer Stephen Bennett) a dazzling sunburst apotheosis, but they are beside the point when Charlip can’t fill space with these characters as well as the puppets do. Indeed, his 12-part drawing of the hoop-dance suggests a performance far more pliant, vibrant, archetypal than the constricted, perfunctory one that he provides.

In announcements and an article in the MOCA house organ, “Amaterasu” is called a work-in-progress. But no such designation appears in the program, though it should: Several key sections are barely sketched in.

For example, the resolution of Charlip’s work--like the fate of the earth in the original myth--depends on a dance that Inari (patron deity of Japanese actors) performs to lure Amaterasu back into the world. Charlip obviously sees this sequence as an outrageous parody of every lurid dance-of-the-seven-veils kootch number ever attempted on stage or screen.

However, after a sly, teasing opening, nothing develops. The dance is simply not there yet. Yes, we know what Charlip wants to express--but, even at MOCA, choreography should be much more than just a conceptual art.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.