U.S. Youth Sits in Prison as Spain’s Legal System Grinds Slowly

- Share via

BARCELONA, Spain — On March 13, 1987, Conan David Owen landed at Barcelona airport from Santiago, Chile, worn out but elated from his first stint as a photographer on a foreign assignment.

At customs, the 23-year-old from the Washington suburb of Annandale, Va., spread his cameras and two suitcases on the counter for what he thought was a routine check. Fifteen minutes later, he stood in a room off the main customs area and watched a police officer poke and squeeze the sides of the larger, buff-brown suitcase.

“Coke or heroin, which is it?” he asked Owen bluntly, and then methodically sliced open the suitcase lining. Sixteen plastic freezer bags, filled with a powdery white substance, slid one after another onto the table.

“My heart fell down to my shoes, my stomach came up through my mouth,” Owen now recalls.

Straight-Arrow American

Owen’s past showed a clean slate, and he fit the bill of a straight-arrow American.

In 1986, he graduated with honors in photojournalism from Syracuse, where he had a scholarship from the Reserve Officer Training Corps. He was to enter active service as an Army lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps in the spring of 1987. In the meantime, he was scouting for free-lance jobs.

A year ago February, he landed a $1,000 contract to take travel shots in Chile and Spain for a Mexico-based tourist agency. A 3-day expenses-paid stay in the Mediterranean port of Barcelona was part of the deal.

Owen spent his first night in Barcelona handcuffed to an airport lounge chair. The 6-hour questioning at customs told him that he was in big trouble, and he mulled over his KLM flight that had made stops in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and Amsterdam. His luggage, except the camera gear, had been checked straight through.

Switched Bags

“Even when they asked if I minded if they cut open the suitcase, I said, ‘Go ahead, it’s not mine,’ because, as far as I knew, I wasn’t hiding anything,” Owen said.

The cocaine-laden suitcase, according to drug trafficker George Barahona’s recent court confession in Alexandria, Va., another Washington suburb, was a look-alike version of a bag filled with travel brochures he had asked Owen to take to Spain. An accomplice in Barahona’s ring made the switch in Owen’s room at the Conquistador Hotel in Santiago on the eve of his flight to Barcelona.

Owen’s father, a 56-year-old insurance investigator, flew to Spain the day after Conan’s arrest and, with the help of the U.S. Consulate, arranged for a lawyer.

“It was close to the Spanish Father’s Day, San Jose,” Ernest Owen said. “People were dancing outside the Cathedral. I thought, ‘Conan ought to see this,’ and I went in and lit a candle. When this candle burns down, he will be out. Things didn’t turn out that way.”

Now, nearly a year later, Owen still is behind bars at Barcelona’s Modelo Prison. He is charged with smuggling 3.9 pounds of cocaine with a street value of approximately $200,000. He faces a 10-year sentence if convicted.

In Spain’s tangled judicial system, largely unreformed since World War II, he also faces the prospect of spending two more years in jail before his case comes to trial.

A judge turned down bail, fearing that Owen would skip the country.

Documents sent from the United States, including Owen’s ROTC records and an explanation from the U.S. Army that he would face military problems if he left Spain with a trial pending, failed to soften the judge’s decision.

“I can’t do anything for myself. That’s the worst thing of all,” Owen said during a 2 1/2-hour interview at the prison.

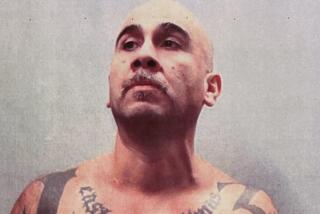

Dressed in a gray running suit and his black hair cropped short, Owen raised his hands helplessly. “Some days,” he said, “you just want to know--when is this all going to end?”

Civil guards with machine guns stand watch at the doors and sentry boxes of Modelo, a mud-colored, four-story building in downtown Barcelona that was built in 1903 to hold 650 prisoners. It now houses 2,380 inmates, with up to six convicts and detainees living in one-person cells.

On Cellblock 1, the only wing with heating, Owen shares Cell 92--two beds long and one bed wide--with two Spaniards accused of drug dealing.

“It’s not the feeling of being dirty or crowded,” Owen said, “because I’ve spent the night in holes I’ve dug in the ground for the Army with two other people.

“That was fine, because I knew I could get out and walk through the woods or, after a rainstorm, come out from under my poncho, and life would be normal again. It’s the knowing there’s no alternative at your command.”

Owen speaks fairly fluent Spanish, which he gets from his Honduran mother. But he does not mix much with other inmates, who include convicted murderers, rapists and bank robbers.

Day to day, he says his real concern is “to keep from going stir crazy.” He writes an average 10 letters a week to family, friends and unknown well-wishers and reads as many books as he can get his hands on, from spy thrillers to history.

Except for two basketball games a week, he gets little exercise because the yard has been under repair for five months.

Sirens ring to announce the head counts, meals and lock-up times. “I don’t keep a log because it is the same every day,” Owen said.

But he does keep notes on events that stand out--the day an inmate, whom Owen played basketball with, tied his sheet into a noose and hanged himself; the day he walked in to find his cellmate shooting up heroin; the day the warden put fresh fruit on the menu.

Members of a Barcelona support group, eight Americans and Spaniards who call themselves Candles for Conan, visit him regularly.

Ron Brown, a 35-year-old evangelical pastor from Phoenix and a member of the group, believes that many U.S. efforts to help Owen have backfired.

“The stones they turn over in the United States get picked up here and thrown back at him,” Brown said. “He is victim of anti-Americanism, I have no doubts.”

On Feb. 9, U.S. Atty. Gen. Edwin Meese III traveled to Madrid to sign a legal treaty unrelated to Owen’s case. But he served notice that he had brought Barahona’s confession, which cleared Owen, to Spanish authorities.

Two days later, the conservative Barcelona daily La Vanguardia headlined its story: “U.S. justice minister seeks release of agent jailed in Barcelona.” It asserted Owen was “a secret agent of the American Navy.”

Owen’s lawyer, Ana Campa, says the Spanish news media have misconstrued Owen’s circumstances, partly because of an overly sensitive reading of U.S. intentions in Spain.

“In recent trips to Peru and Venezuela, our own foreign minister took a personal interest in specific cases involving Spaniards jailed on drug charges,” Campa said. “Then Meese did the same thing here, but it was seen in a different light.”

Last May, an editorial in the conservative Madrid daily ABC viewed the U.S. congressional inquiry and White House interest in the case (Owen worked as a photography intern at the vice president’s office in the summer of 1984) as attempts to pressure Spain’s legal system.

“If you have a problem (in the United States), you write to your congressman or senator and raise hell,” Owen said. “If I am a CIA agent, I certainly would have escaped by now.”

But Owen’s hopes are pinned on Barahona’s confession.

A naturalized American born in Ecuador, Barahona admitted to duping Owen in a plan that called for using an unwitting U.S. citizen to carry Bolivian cocaine from South America to Europe. The money from Owen’s switched suitcase was to finance bigger drug ventures in the future.

Owen met Barahona through a cousin who works at the National Geographic Society’s magazine. Owen had no suspicions. To him, Barahona was “a regular middle-class-looking guy” and several photographer friends congratulated him on his good luck.

In Santiago, Chile, Barahona introduced him to Julio Prieto-Garcia, a Spanish consultant for the Sorosa travel agency, who left on an earlier flight for Barcelona but promised to pick up Owen at the airport there.

Police investigations showed a flurry of intercontinental telephone calls among members of Barahona’s ring, who apparently witnessed Owen’s airport problems and put out the alert.

Both Barahona, given a 2-year suspended sentence in exchange for turning state’s evidence in Virginia, and Prieto-Garcia, who is still at large, are wanted in Spain in connection with the case.

Justice Ministry sources decline to comment on the weight of the confession in a Spanish court.

“There is nothing in Spanish law that says a fugitive’s word can or cannot count as evidence,” said Alberto Elordi, the ministry’s spokesman. “It will be entirely up to the prosecutor to decide.”

So, like the nearly 12,000 Spanish detainees languishing in prison with their cases caught in a slow-moving court process, Owen may have a long wait.

“It seems so unreal. It’s just like the movies. But it’s not a movie at all,” Owen said wryly.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.