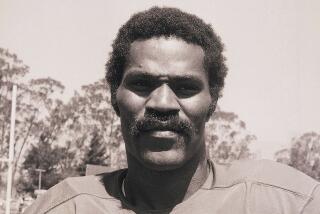

Jim Jordan, Fibber McGee of Radio, Dies

- Share via

Jim Jordan, who lived for 14 years as Fibber McGee in an imaginary home at 79 Wistful Vista that featured the most disorganized closet in the land and who will live even longer in the hearts of Americans who listened to him faithfully each Tuesday night on radio, died in Los Angeles on Friday at the age of 91.

At his death, Fibber McGee had outlived Molly, his show-business and real-life wife (Marian Jordan) by almost 27 years. Friends said he had been hospitalized at the Beverly Hills Medical Center for about a week after a fall in his home.

Although the show that spawned such airwave maxims as “Tain’t funny, McGee,” “Heavenly days,” “You’re a hard man, McGee,” “Dad-rat the dad-ratted . . .” and “Why, mister, why, mister, why, mister, why?” had been off the air since 1952 (it continued briefly as a segment on the old “Monitor” series), Jordan remained a popular figure in Los Angeles and continued to receive dozens of fan letters a week at his Beverly Hills home.

In recent years, his health precluded many outings, but Jordan continued to sit at the dais at the bimonthly meetings of the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters, a group he helped found. And although his legacy will be in comedy, he could be a stern, unsmiling man when those meetings failed to please him.

Although most living Americans will remember “Fibber McGee and Molly” as a full-blown radio production with a cast of characters that included Harold Peary as McGee’s neighbor, Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve, who went on to star in his own show, the Fibber-Molly tandem had its genesis in far more humble surroundings.

Jim and Marian Jordan were childhood sweethearts in Peoria, Ill. He was the son of a farmer who aspired to be a singer, and she was a coal miner’s daughter who wanted to teach music. They combined their lives and talents in 1918, the year they married, formed a vaudeville act and went on the road at $35 a week. But not for long.

Drafted During WWI

Jordan was drafted in World War I, and when he returned two children were soon born. The Jordans abandoned the road in favor of their new family and stayed in Peoria, singing for civic clubs and in churches.

Jim’s brother bet them $10 that they couldn’t get a job on the local radio station, and even though they collected the bet, Peoria’s station WIBO could not pay them enough to feed themselves, much less two children. Back to vaudeville they went, but by 1927 radio called again, this time station WENR in Chicago.

They went on the air there as “The Air Scouts,” according to the radio anthology “Tune in Yesterday,” and it was on that show that Marian Jordan perfected the little-girl voice that was to bedevil Fibber nationally several years later.

Probably the single most important event in their career came in 1931, when they teamed with writer Don Quinn in a show he created for them called “Smackout.”

Played a Grocer

Jim Jordan played a grocer who bragged that he stocked all manner of necessities in his store but when asked for an item would search for a moment and then admit, “Guess I’m smack out of that.” What he never was out of, however, were prevarications. Quinn provided him with an endless supply of tall tales.

The show ran for four years in Chicago before an advertising executive for Johnson’s Wax heard it and put it on the air coast to coast on the old Blue (NBC) Network. It briefly ran on Monday nights opposite “Lux Radio Theatre” but by 1939 had moved to Tuesday nights on NBC’s Red Network, where it remained for 14 years.

By then, Quinn had converted the grocer into a small-town, middle-class businessman who lived at 79 Wistful Vista (Sad Street) and who welcomed to his door such unforgettable characters as Wallace Wimple (wed to “Sweety-Face, my big fat wife”); The Old Timer (“that’s purty good, Johnny, but that ain’t the way I heared it”); Beulah the maid (“somebody bawl for Beulah” and “love that man”), and Myrt, Fibber’s omnipresent telephone operator (“how’s every little thing, Myrt?”)

Handful of Actors

Because of radio’s unseen magic, a handful of actors portrayed a roomful of characters. Marian Jordan was Sis, Teeny, Geraldine, Old Lady Wheedledeck and Mrs. Wearybottom. Bill Thompson (along with Cliff Arquette) was The Old Timer and Horatio K. Boomer, Nick Depopolous, Whimple and Uncle Dennis; Hal Peary was Gildersleeve and Marlin Hurt, a white man, was the black maid, Beulah.

Even Harlow Wilcox, the announcer and Johnson’s Wax pitchman, was an integral part of McGee’s family. Fibber called him “Waxy” and teased him as comic dialogue gradually segued into his commercials. Many of the characters existed only in the listener’s imagination. Fibber talked with Myrt, but the non-existent Myrt never answered, as in this typical phone conversation:

“What’s that Myrt, your uncle smashed his face and broke one of his hands?” “The poor man,” Molly would say, overhearing Fibber’s one-way conversation. “Did he fall down the stairs?” “Nope,” Fibber would respond. “Just dropped his watch.”

And then there was the closet.

In a 1982 interview with The Times, Jordan discussed its origins:

“We were always looking for a running dingus, a gag. We tried all kinds of things to keep a gag going but nothing worked. Then a writer did a show about how Fibber was slovenly and when he opened a hall closet door, everything fell out.”

Tuesday Show

Each Tuesday, America gathered in front of its radio to hear this monument to sound effects men:

A split second after Molly had frenetically warned, “Don’t open that closet!” could be heard the first trickle of debris. Things would crash to the floor in alternating cacophonous waves and after the waves had crested would come a blessed moment’s silence and then the coda--the thin ring of an obviously weary bell. It was Fibber’s cue to remark, “Gotta straighten out that closet one of these days.”

Within a few years, the program had shifted to Hollywood from Chicago, and Jim and Marian Jordan had moved from $35-a-week vaudevillians to $3,500-a-week radio entertainers who consistently topped Bob Hope and Jack Benny in the weekly ratings.

Throughout World War II, the Jordans, Quinn and a new writer, Phil Leslie, injected patriotic messages into their comedic routines: Fibber paying premium prices for black market meat in a time of meat rationing only to find the meat spoiled; episodes illustrating the need for gas and rubber rationing. But when the war ended, it wasn’t only gasoline and tires that became abundant. Peace produced television sets, and life on Wistful Vista was never again to be as full.

Close-Knit Group

Jordan recalled in 1982 that his radio family was as devoted as his own--that his associates were so close-knit and sure of themselves that “we didn’t even look at the script until a half-hour before we went on the air.”

Old transcriptions of the show broadcast at odd hours made him a cult figure to a new generation of fans, who wrote him for pictures despite Jordan’s contention that “no one cares about the old days.”

He remarried--to his current wife, Gretchen--after Molly died and spent the last years of his life choosing not to play the old transcriptions of his radio shows that helped fill his home. The son, Jim Jr. and daughter, Kathryn Newcomer, born to Molly and him produced seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren whom he saw often.

He stayed home, except for the bimonthly forays to the Sportsmen’s Lodge and the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters’ meetings, where the diminutive Jordan was treated with a reverence that seemed to alternately please and annoy him. He suffered a heart problem, struggled with a series of bladder infections and lamented that antibiotics “make me sicker ‘n a dog.”

He also looked back fondly on his and radio’s Golden Years:

“I guess it’s enough to think that even when old Jim Jordan is gone, Fibber might last for awhile.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.