Soviet Change Is Under Way, but Can American Thinking Keep Up? : Nationalism, Not Communism, Is Today’s Threat

- Share via

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union will convene on June 28 in what we are told will be a meeting of historical importance and a test of Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s power.

Few people are aware that June 28 happens to be the date of a historic anniversary. It was exactly 40 years before, on June 28, 1948, that the much vaunted--and feared--unity of the international communist movement was broken. On that day in Moscow, communist Yugoslavia was publicly condemned and expelled from the Cominform, then the association of allied communist regimes.

That break with the Yugoslav communist leader, Marshal Tito, was the end of the mirage of international communism. Soon it became evident that Tito would survive the hostility of Moscow. Within the next decade all kinds of other communist governments chose to declare their independence from--indeed, their hostility to--Moscow. Within another 10 years a host of Communist parties (the Italian one, for example) declared their independence from and their unwillingness to abide by Soviet directives or models.

One of the great errors of our times is made by people who mistake the speed of communications for the movement of ideas. The first has become incredibly rapid; the second has become incredibly slow--especially on the level of political ideas and statesmanship. While American diplomacy did react to the Tito-Stalin break (because of its blatantly obvious nature), American public opinion and governmental policy continued to be obsessed with the danger of international communism for a long time afterward. The peak of our national obsession with communism (and the peak of Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy’s national popularity) came, for example, after Josef Stalin had died and the Soviet regime was beginning to be liberalized by Nikita S. Khrushchev.

Another prime example of such regrettable time lags was Richard M. Nixon’s China opening in 1971, the announcement of which established the sterling reputation of Nixon and Henry A. Kissinger as great visionary statesmen. This event came 20 years after others had first recognized the differences between China and the Soviet Union, and 13 years after these differences had come out into the open.

Many things have happened during the last 40 years, but one of the most important (if not the most important) developments has been that the Soviet leadership has finally seen the necessity to acknowledge the failures of communist rule, too. What will happen on June 28 and thereafter we do not know. But even if Gorbachev’s brave, commendable and creditable leadership were to fail, this would happen not because of some remnant of the appeal of orthodox communism among the Soviet peoples. Rather, it would be because some of their national characteristics include a fearful suspicion and inexperience of life in a society and a state bereft of rigid restraints.

There are two important things for the American people and their politicians to keep in mind. One is this: The equation of American patriotism with anti-communism must now be buried--not only for moral but also for pragmatic reasons--once and for all. There are not many Americans who still believe that the principal danger to their country is communism. But there are still enough of them, in important positions. A good example is former Lt. Col. Oliver L. North and, in a way, President Reagan himself. Because of their anti-communist ideology, they apparently had few compunctions about dealing with a Panamanian dictator even after he had proved to be a magnate among drug dealers. Had Manuel A. Noriega declared that he was getting addicted to communism rather than drug money, the Marines would have landed in Panama City long ago. Beneath this American ideology of anti-communism lurk not only enormous vested interests but also a psychic need--very evident in many of Ronald Reagan’s statements--to seek mental comfort in positing a foreign empire representing evil as a contrast to an America that represents what is not only good but also best in the entire world. Even now we cannot be sure that his experience in Moscow has changed this set of mind.

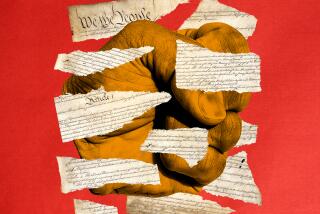

The other matter to keep in mind is that the governing idea of the world in the 20th Century is neither communism nor capitalism but nationalism. This was recognized long before Gorbachev and long before Tito by some men, including young revolutionary socialist Benito Mussolini, who nearly 80 years ago realized that he was an Italian first and a socialist second and that international socialism (like international communism or international capitalism) was an illusion. His founding of a Fascist Party many years later was but a consequence of that. Another 70 years later all of the globe’s communist states and parties are national, not international, ones. And it is nationalism more than communism--more precisely, various nationalisms of the Third World--that often rises to threaten the interests, the security and even the traditional constitution of the United States as well as those of the Soviet Union.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.