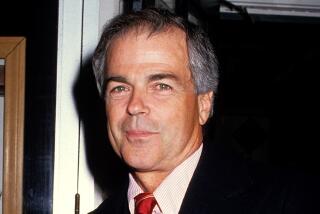

The Great Life, Bad Days of Joshua Logan

- Share via

NEW YORK — It was, he wrote in his autobiography, an “up-and-down, in-and-out” kind of life.

Literally up-and-down. For most of his directing career, Joshua Logan, who died here Tuesday at 79, had days--weeks--when the good ideas wouldn’t stop coming, to the point where he was unable to sleep. Then Logan would tumble into an equally unreasonable despair unable to function for months.

It took years to discover that the remedy for this condition wasn’t psychoanalysis but a chemical, lithium. Logan had gone public about his problem earlier (at some risk to his career: Who wants to hire an unstable director?) and he went public about its solution, too.

Actually his career was not at risk. Almost any producer in the 1940s and 1950s would have hired the “unstable” Joshua Logan, for he had the golden touch. His shows invariably sent people home feeling better about themselves, about mid-century America and about the theater. They combined rowdiness and tenderness, and often included a flash of bare skin.

Where George Abbott specialized in directing musicals, and Elia Kazan concentrated on straight plays, Logan was a whiz at both--and at making movies, too. A cynic might say that every Logan show felt like a musical, whether it had songs or not, but that may be just another way of saying that Logan’s work had twice as much vitality as ordinary directors.

He was a great field commander and a great psychologist. He could work with a big star like Mary Martin (“South Pacific”) and an emerging playwright like William Inge (“Picnic”) and in each case know when to bully and when to ease back. Martin adored him. Inge never quite forgave him for insisting that “Picnic” needed to have a happy ending--but the playwright admitted that in terms of what the public wanted to see, Logan was probably right.

Most directors walk away from a show on opening night, particularly if the reviews are bad. After the opening of “Wish You Were Here” (set around a summer-camp swimming pool: More bare bodies), Logan agreed with the bad reviews, but thought that the show could be fixed. He worked on it for the next six weeks, invited the critics back and it became a sort of hit.

This was not a man who gave up easily. I discovered this when I visited him just a year ago in his big East River apartment, with some questions about Inge.

Logan had written to me that he wasn’t in good shape. But I wasn’t prepared to find him laid out on the sofa under a plaid blanket, virtually unable to talk.

This was the result of a wasting disease identified in the obituaries as supranuclear palsy. Logan’s mind was there, but his body wasn’t responding to command. To make things worse, Logan had just had a tooth removed.

But he had agreed to be interviewed, and he would go through with it. A microphone was brought to his mouth and he formed his answers to my questions as best he could. The magnified sounds were not very clear, and he knew that it was hard to make sense of them.

So he would watch my face, his blue eyes dancing, and if something hadn’t registered, he would repeat his answer, even more carefully.

He wasn’t annoyed with me for failing to catch his meaning, and he wasn’t mad at himself for not having made the words come clearer. It hadn’t worked? OK, let’s take a breath and try it again. Twenty minutes of that was all I could take, but he would have gone on with it all afternoon.

That afternoon I saw what may have been Josh Logan’s real secret as a director. Patience.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.