Fate of Alleged Kraft Victim Torments Kin

- Share via

The day he disappeared, Paul Joseph Fuchs had set the table for a Sunday dinner of his mother’s chicken paprikas, the family’s favorite Hungarian dish. In a hurry to join friends, he ate ahead of his parents and three brothers.

Young Paul, as the family called him, walked past the redwood gate of their Redondo Avenue home in Long Beach and jumped into a car that had pulled up.

That was Dec. 10, 1976. His family never saw him again.

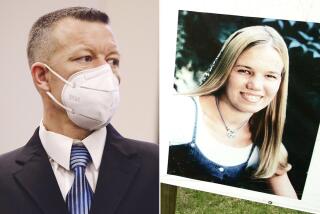

The only word that Paul and Elizabeth Fuchs have received about their 19-year-old son came in the fall of 1983. The district attorney’s office, two Orange County Sheriff’s Department investigators told them, believed that their son had been killed by Randy Steven Kraft.

Kraft, now 43, is on trial in Orange County Superior Court in Santa Ana, charged with 16 murders. But prosecutors have accused him of an additional 29 murders, including six in Oregon, two in Michigan and the rest in the Southland.

Fuchs’ name is among those other 29. The Fuchses have only two clues about their son’s fate:

Prosecutors claim that Kraft kept a coded list in his car that was a score card of his victims. The investigators told the Fuchses that one of the entries, an expletive, stood for their son.

Also, investigators learned that Fuchs (pronounced Fukes) was last seen at the Ripples Bar in Long Beach. It’s a bar Kraft frequented. The word “Ripples” is on the list found in Kraft’s car. Whatever other evidence prosecutors may have has not been disclosed. No body was ever found.

In 1983, Paul Fuchs recalls, he told the two sheriff’s investigators, “I still held out hope that he was alive. But one of the officers shook his head and said, ‘Don’t hope.’ ”

The finality of the investigator’s tone convinced the Fuchses that their son was dead.

It has been almost 12 years since his disappearance. But Dorothy Wilbur, a neighbor of the Fuchses, who now live in east Long Beach, says Elizabeth Fuchs, 69, still cannot get through a day without crying over her son.

Paul Fuchs, 65, says that sometimes he has to leave the room when his wife breaks down because he has run out of words to try to comfort her.

Elizabeth Fuchs says time will never help.

“My mind is almost gone,” she says, crying with her head in her hands.

The Fuchses and their sons have faced obstacles most people only read about. Descendants of Germans who settled in Hungary (their accent is German, not Hungarian), they escaped from the Soviets in the uprising of 1956.

“We left everything behind,” said Paul Fuchs, who had been a farmer in Hungary. “We came here with just the clothes on our backs --with three young sons and my wife pregnant with another.”

The child she was carrying was young Paul. Elizabeth Fuchs said she and young Paul had a special relationship from the beginning.

Her husband picked up odd jobs and then got into construction work, first in New Jersey and finally in Southern California. She cleaned houses and took her son Paul with her.

“That’s why he could not stand to be gone for half a day without calling me,” she said.

The year before he disappeared, the Fuchses had taken him back to Hungary, to the small farm village of Nemetbanya where his parents and brothers had lived. Describing young Paul zipping through the back roads of Hungary and Germany in an aunt’s car, Paul Fuchs smiled.

A Wilson High School graduate, Fuchs was parking cars and doing other low-paying jobs while trying to decide what to do with his life, his father said.

The Fuchses dote on their son’s qualities. He was a talented artist. He could cook. He could sew and iron. And he never went anywhere unless he told his mother when he would be home.

One typical note he left read: “Mom, I went to Rich’s house. Be back in a few minutes. He lives between 7th and 8th St. Love, Paul.”

The day he disappeared, the Fuchses pored through every name in his address book, hoping someone had seen him. But none of them had. He left in such a hurry he forgot to take his wallet. He had made no withdrawals from his bank account.

The family never discovered who had picked him up at the house.

The Fuchses were frustrated that the Long Beach police listed him as a runaway. He would never leave without calling, the Fuchses told them. And who sets the table for Sunday dinner if he’s going to run away?

“The police, they tell me if they stopped to look for all runaways, they could never get anything else done,” Elizabeth Fuchs said. “They would not help me. I called and called them.”

Paul Fuchs described some of the family’s torment between 1976 and 1983:

“Every time a body was found, someone from the authorities would call us. Did Paul have a chipped tooth? How tall was he? Every time, it was agony waiting to see if it was our son.”

Their son was scheduled to appear in court in San Pedro on a misdemeanor citation for drinking beer with friends. The police came to the Fuchses’ door when he failed to appear. The Fuchses then went to court the next several days in case he showed up.

Then there was the time the elder Paul Fuchs was working at the naval shipyards in Long Beach and a large ship arrived from Oregon. He noted the name “Paul Fuchs” among the crew. The family got excited and tracked down the name to see if it might be their Paul. It wasn’t.

After Kraft’s arrest May 14, 1983, the Long Beach police sought help through the newspaper from anyone with information about any young men who might have met with foul play. The Fuchses called right away.

Kraft is not charged with killing their son. But if Kraft is convicted and his trial moves into a penalty phase, prosecutors have said they intend to present jurors with evidence of many of those other 29 murders. Kraft has denied killing anyone, including Fuchs.

It is still unclear what would be included about Fuchs’ disappearance if the trial gets that far.

The Fuchses say that at some point they want to attend the trial, which is about to enter its third week of testimony. But they worry about how they will feel seeing Kraft for the first time.

The Fuchses say it is frustrating that Kraft probably will never stand trial on charges of killing their son. More frustrating, they say, is not knowing what happened to young Paul.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.