20th-Century Revolutions Wear a Mantle of Cruelty and Failure

- Share via

These are not good times for the revolution. We see the Soviet Union in the throes of discarding its revolutionary legacy. Algeria and Yugoslavia experience violent popular reactions against their single-party authoritarian governments, product of successful national liberation movements. The national liberation of Vietnam has ended in political repression and social and economic stagnation. Cambodia’s produced genocide (and the story there is not over). National liberation in Africa has more often than not ended in political squalor and economic deprivation worse than the conditions experienced under colonialism.

Yet all these affairs began in high ambition, idealism and self-sacrifice. The state of affairs in Yugoslavia--where, as the official news agency itself bitterly notes, “43 years after peace in Europe and at the threshold of the 21st Century, (Yugoslavs) are queuing for black bread”--betrays a heroic national movement of resistance to Nazi occupation. Algeria’s young people have turned in anger against the leaders who conducted the struggle for independence.

Past revolutions worked. The French Revolution is the prototype of modern Western political revolution. It went through its bad times--terror, war, the dictatorship of the Directorate--but it liberated popular energies, confirmed France as the first nation in Europe, while its ideas and example transformed Europe and, indeed, the whole course of modern history.

Out of the French Revolution came the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the promulgation of republican government throughout Europe, reformed legal systems, expanded popular education, the reform of science and much else.

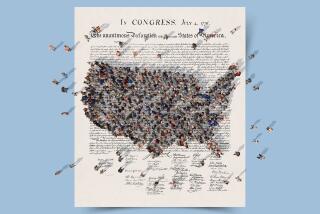

The American Revolution was the prototypical national independence movement. The influence of American ideas about national self-determination transformed South America in the 19th Century, Central and Eastern Europe in 1918-1920 and exercised a powerful influence on Asia and Africa in the 1940s.

The French and American revolutions were chiefly motivated by values. Those who made them mostly did not think that they possessed an infallible plan for reorganizing society. The new political order had to be debated and developed. It remained to be invented. The revolutionaries defended the values of individual freedom, individual rights and representative government, and opposed monarchy or monarchical abuses, inherited privilege, etc. Theirs were practical objectives, achievable values.

The revolutionaries had classical models in mind, certainly, of Greek citizenship and Roman republicanism, but they acted out of moral and emotional conviction, whereas Marx and Lenin condemned emotion and conventional, “bourgeois,” moral considerations as obstacles to revolution. The difference is basic.

Marxism has been the dominant influence on 20th Century revolution, and Leninism provided the model of single-party government that most national liberation movements have chosen to adopt. Marxism has claimed to be scientific, an objective interpretation of history. Leninist revolutionaries have believed that they are in possession of a kind of knowledge about society that goes beyond emotion or moral judgment.

The Marxist poet Bertolt Brecht wrote: “Sink into the mud, embrace the butcher, but change the world!” This is what all too many 20th-Century revolutionaries have done, convinced that the assured result was a society where men would be truly happy, while whatever had been done to achieve this condition would be understood as the product of necessity.

It is a crucial point, however, even if it should be a banal one, that those who embrace the butcher usually are left by history in the butcher’s embrace. Crimes eventually have to be accounted for--as is happening in the Soviet Union today.

Human values count. Political ideologies, on the other hand--grand theories about how society and geopolitics function--may or may not contribute to our understanding of society at a given moment, but in any case they eventually pass. Their weaknesses emerge; they come to be seen as the product of a particular time and circumstance. Other ideas take their place. Those who lived by the ideology are left behind.

The influence of political ideology has convinced too many people who meant well that good comes from the necessary evil, hence that evil, as Hannah Arendt described their belief, “is but a temporary manifestation of a still-hidden good.” It is this which repeatedly has led political movements, begun in generosity, to end in cruelty, decay and failure.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.