A Maoist Until They Crippled His Son : DENG XIAOPING <i> by Uli Franz, translated by Tim Artin (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: $19.95; 322 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Since classical times the Chinese have had an almost obsessive relationship with their history. When things went awry, rather than looking forward to the future and change, they tended to look backward toward the past hoping to right the situation through study of the Golden Age of the early Zhou Dynasty, which they viewed as the model of societal perfection.

In fact, one of the most important responsibilities of government was the maintenance of the official dynastic historical records (among which the biographies of great thinkers and statesmen of the past were prominent), which dictated whether a specific biography would be included, rewritten or dropped. History may have been revered, but as the intellectual property of the state, it was revered selectively, and the task of selection was entrusted to the legions of imperial compilers who, under the threat of banishment and even death, were charged with making history conform to didactic imperial purposes.

However, there grew up beyond their control another historical tradition of a more popular nature, which included what came to be know as waishi and waizhuan, “outside” or “unofficial” histories and biographies which, being more popular in nature, used unverified and undocumented sources.

Contemporary Chinese communists have been every bit as custodial as their earlier Confucian forefathers about their party’s history, and particularly mindful of the powerful role that biography can play in political life. Moreover, they have evinced no more inclination to open up archives to independent historical research than the emperors of old. This has left historians, and particularly biographers who want to go beyond published documents, very much on the outs, forced to write modern waizhuan and waishi from whatever scattered and often unreliable alternative sources they can get their hands on. While such “outside” historians have the virtue of being free of state control, by being denied access to key figures and their papers, they face a daunting task that all too often dooms their work to being less than convincing.

Uli Franz is the first Westerner to really take on the subject of China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping. He tells us in his foreword that “by now, the world public has a right to find out more about Deng’s career than his Party has let us know.” Few could cavil with this statement. But such pronouncements do not help a biographer overcome a Communist Party’s reluctance to make crucial sources available. Franz tries to make a virtue out of this predicament, but his efforts are less than convincing. “Anyone wishing to do research in China has to choose between two extremes,” he tells us. “Either he seeks the green light from the very very top, in which case archives and mouths open as though by magic, or he pursues ‘history from below,’ as inconspicuously as possible. I chose the latter path. I descended to the ‘grass roots.’ ”

The problem with Franz’s book is that he did not in fact have a choice. He was forced to turn to the “grass roots” and to the tradition of the waizhuan because the “very very top” was not about to place the delicate task of party hagiography into the hands of a West German who, after arriving in Beijing as a self-confessed Maoist, soon turned into a born-again laissez-faire capitalist. What became ironic about his efforts was that although the author and his subject were both in China, Franz’s search for documentation evidently ended up being most fruitful in Taiwan, Hong Kong and France, where Deng had spent six years in the early ‘20s working and organizing, and, incidentally, cultivating an abiding taste for croissants. Particularly in writing about Deng’s early years one feels Franz’s frustration. Although he uncovers many new French records about where Deng lived and worked, they are by and large of a rather dull and untelling nature.

One can’t fault Franz for being unable to break through the gag order that the Chinese Communist Party uses to shield its leaders from public scrutiny. Franz was eager, and no doubt if there was material in the commonwealth to be had he would have found it. But, with Deng, he was up against more than his own enthusiasm and energy; he was someone locked outside trying to describe what it was like inside. With few other sources to rely on, he was left to try and leaven his loaf with all too many speculative refrains such as: “Memories of his previous fall must have welled up in him,” so that like many other biographical efforts on other Communist Party leaders such as Mao Zedong and his wife, Jiang Qing, there is finally a patchy thinness to his results.

This sense of thinness is exacerbated by the inconsistent way in which Franz footnotes his sources, citing some quotes and facts but not others. Just as he is vague on the dust jacket about his own background--listing himself only as a “German author and photographer . . . who worked as a correspondent in Beijing from 1977-1980”--so is he vague about where his information came from. It is a failure that is particularly infuriating in a book like this one, which, because of his promise that he is bringing us new information, continually begs the question, “Is he saying anything new, and if so, where does it come from?”

And, finally, there is the question of the book’s uneven translation. Although much of it is passable, many phrases that have by now come to have standard English translations--such as “socialism with Chinese characteristics” or the “four basic principles”--have been retranslated by Tim Artin as “socialism of the Chinese stamp,” and the “four absolute fundamentals,” imbuing the work with distracting awkwardness.

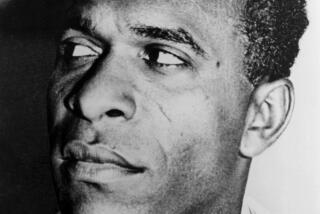

But in spite of all these criticisms, Franz’s book is still well worth reading. It contains an interesting collection of photographs showing Deng with family members and other Chinese leaders. Moreover, Franz has done a good job stringing together what we do know about Deng, as well as adding some new things we did not already know into a full-length biography.

Amazingly, even though Deng is undeniably one of the most significant figures of the 20th Century, it is the only real biographical attempt available in the English language. Complete with a good chronology, it allows us for the first time to view the full sweep of Deng’s long life. We begin to understand how Deng--a militant revolutionary who left for Europe and the Soviet Union in 1920, led two military uprisings in Guangxi Province in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, joined the Long March in 1935 and then followed Mao unswervingly into power as a believer in class struggle and militant revolution--finally became disillusioned with politics as the answer to China’s poverty and backwardness.

Franz describes how, in the aftermath of the Hundred Flowers Movement in 1956--when for the first time Mao allowed intellectuals to speak out--Deng led the savage counterattack known as the Anti-Rightist Movement, which destroyed over a million writers, artists and scholars. Then he shows us piquantly how Deng’s politics began to change radically when, 10 years later during the Cultural Revolution, he himself was cashiered by Mao, sent to a factory to work and was unable to help even his own favorite son, Deng Pufang, who was persecuted and ultimately rendered paraplegic by the Red Guards. It was largely as a result of these experiences that he began reassessing his priorities for China, allowing his practical side to assert itself over his ideological side, until he was exhorting Chinese “to seek truth from acts,” not politics.

Since the political odyssey of China has in so many ways turned out to be Deng’s own, it is important that we be able to see, however incompletely, the evolution of this man’s life and thinking. In this sense Franz’s book is a great help. But, it also reminds us of the endless fratricidal struggles that have for decades rocked the Chinese Communist Party’s inner circle, reducing their revolution to little more than trench warfare for power and position between battling cliques of leaders. Franz’s account gives an important glimpse into this unsavory process. And, what gives the book a unique yeastiness is the way in which these revelations evidently affected the author’s own politics. Like Deng and so many others, he too undergoes a dramatic change of heart. Having gone to China as an admirer of Mao, he finishes his work feeling not only disillusioned with the Great Helmsman’s revolution but even adulatory of Deng and his crypto-capitalist reformers. Instead of damning them as “revisionists” who have sold out the true cause of Marxist revolution, he ends up calling them “courageous avant-gardists” and praises them for having “achieved a breakthrough in the fight against orthodox ideology (and) antiquated dogma.”

The unarticulated message of this book is that revolutionary socialist China is dead. But, as Franz points out, while Deng may be a practical liberalizer in economic matters, he clearly has his limits when it comes to the democratization of politics. Traditional Chinese authoritarianism and Marxist-Leninist centralism conspire in Deng to create a mind that still cannot imagine a China separate from the exclusive leadership of the Communist Party. The contradiction between economic and political liberalization is one that Franz, like Deng, never really addresses. He notes that Deng and his supporters will soon “come to a fork in the path where they will finally have to choose a direction.” But, in many ways they have already come to this fork without Deng having acknowledged it. How he and his cohorts intend to deal with the chaotic consequences of their economic reforms and the increasingly outspoken demands for more political democracy is still far from clear.

Done very much in the classical tradition of the waizhuan, “Deng Xiaoping” is an informative but incomplete biography that in spite of the herculean efforts of its author leaves its subject almost as elusive as before. But it is not likely to be improved upon soon, unless Deng himself suddenly steps out of that long tradition of secretive leaders and unburdens himself to the world for posterity or until that unforeseeable time in the future when the archives in Beijing are finally opened.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.